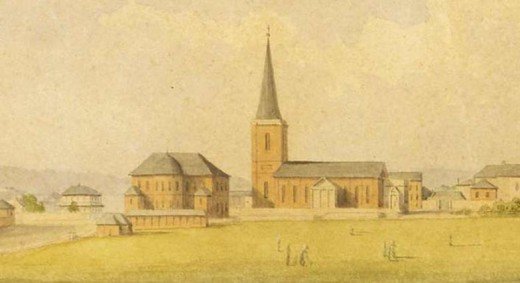

Nash’s Foley House 1794, Haverfordwest sourced from wikimedia commons here

With Greenway’s design of Hyde Park Barracks (and 80 known works and attributions) a case may be made for his acquaintance with John Nash (1752-1835) and emulation of a range of motifs evident in Nash’s commissions such as:

Relieving arches in series reading as blind arcading (as in HPB main block exterior ground floor treatment)

– Nash’s Foley House, Haverfordwest, Pembrokeshire 1794

– Llanaeron, Cardiganshire, 1794

– Whitson Court, near Newport, Monmouthshire, 1795

– Hereford Gaol, 1796

– The Warrens, Brayshaw, Hampshire, 1800-02

Enclosed gables (as in HPB main block exterior, east and west elevations)

– Nash’s Ffynone, Pembrokeshire 1792-96

– Foley House, Haverfordwest, Pembrokeshire 1794

– Glanwysc, Llangattock, Breconshire c. 1795

– The Warrens, Brayshaw, Hampshire, 1800-02.

Hemispherical domes (as in HPB gate lodge domes)

– Nash’s mausoleum of Thomas Nash, Farnigham, Kent, 1778

– County House, Stafford, Staffordshire, 1794

– Sundridge Park, Bromley, Kent, 1799

– Balindoon, Co Sligo c1800

– Design for Bulstrode House, Buckinghamshire 1801-02

– The Quadrant (west side), Regent Street London, 1809-26

Australian colonial architecture may be seen as provincial as the architecture of Greenway’s native Bristol. However, Greenway’s architectural competence and association with John Nash (later the Prince Regent’s architect and the architect who recast Regency London in classical garb) lifted him above many of his peers in Sydney or the English provinces. His shingle-clad Hyde Park Barracks guardhouse domes in their ‘primitive’ simplicity gave Governor Macquarie’s principal Sydney street a metropolitan sophistication.

References

Broadbent, James and Hughes, Joy, Francis Greenway architect, Glebe NSW, Historic Houses Trust of NSW, 1997

Mansbridge, Michael, John Nash a complete catalogue 1752-1835, New York 1991