Historical research is a curious thing. You find a fleeting reference or snippet of information that prickles your interest about a place, a person, an object or an incidence, then find yourself chasing leads that might shed more light on the subject. In this case, it is the mystery of Governor Arthur Phillip’s ‘French cook’.

First Fleet officer Watkin Tench speaks of ‘a French cook, one of the governor’s servants’ in a journal entry in September 1790. According to Tench’s description, this Frenchman had quite distinctive traits – so much so that Bennelong, the Aboriginal man who had been held captive at the Governor’s house for six months from November 1789, would make fun of him. According to Tench,

[Bennelong] constantly made him the butt of his ridicule, by mimicking his voice, gait, and other peculiarities, all of which he again went through with his wonted exactness and drollery.

I’ve long been intrigued by the notion of Phillip enjoying French cuisine in a fledgling colony renowned for its rations and food shortages. With the anniversary of our first governor’s death this month, I’ve started looking into this aspect of Phillip’s domestic life in more depth – with some curious and surprising outcomes, and as is often the case in historical inquiry, more questions than answers!

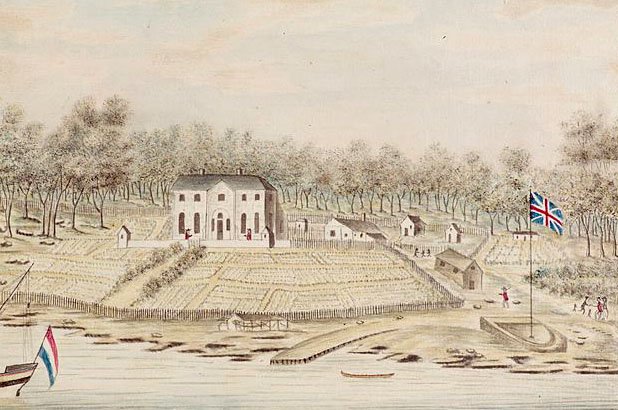

[Captain Arthur Phillip, 1786] by Francis Wheatley. State Library of NSW ML 124

An acquired palate

Phillip, who was fluent in five languages including French, spent two years in France between 1784 and 1786 on an ‘espionage’ mission for the British Home Office. Perhaps this is when he picked up a taste for French cuisine and decided a French cook would enhance his time ‘beyond the seas’ in distant New South Wales. Records indicate that Phillip may have indeed had a French cook, or manservant at least, among his ‘family’ at Government House. The First Fleet passenger list for the flagship Sirius includes two free-status passengers listed as ‘servants to governor Arthur Phillip’. One was Henry Edward Dodd, brought to New South Wales as the colony’s Superintendent of Agriculture, the other, Bernard de Maliez, listed as ‘personal servant to Arthur Phillip’. When Phillip transferred from the Sirius to the Supply to execute a quicker passage to Botany Bay in November 1787, Maliez too transferred, indicating his close working capacity with the governor.

Well catered for

Recording details of a reconnaissance mission to explore new territory beyond the Sydney Cove settlement in April 1788, surgeon John White praises Philip’s ‘steward’ for putting together a provisions package for the governor and his compatriots:

We got to a pleasant little cove, where we dined, with great satisfaction and comfort, upon the welcome provisions which were sent in the boats by the governor’s steward.

It seems very reasonable to believe that this steward would have been the governor’s personal servant, Bernard de Maliez. And if this is indeed the case, White’s reference suggests that the governor’s dietary comfort and concerns were within Maliez’s job description – and his role could possibly be interpreted as being the Governor’s cook.

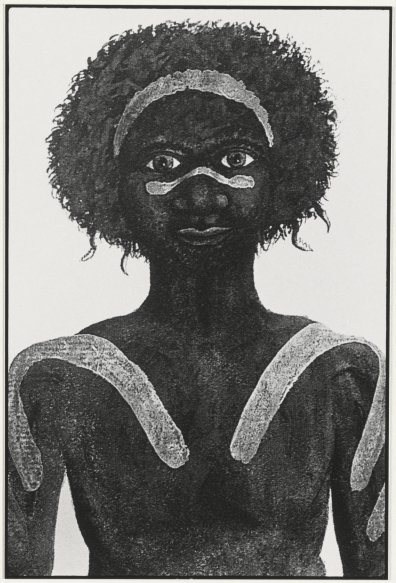

Portrait of Bennelong, John Rhodes, 2002, photographic reproduction of Portrait of an Aboriginal man, named Bennelong, Thomas Watling, c1790, National History Museum collection. National Library of Australia nla.pic-vn4663126-s2 © Jon Rhodes

The Bennelong connection, or confusion?

After being held at Government House for almost six months, Bennelong found an opportunity to escape. Tench reports the incident:

About two o’clock in the morning, he pretended illness, and awaking the servant who lay in the room with him, begged to go down stairs. The other attended him without suspicion of his design; and Baneelon Bennelong no sooner found himself in a back-yard, than he nimbly leaped over a slight paling, and bade us adieu.

According to some published Australian histories, it was Maliez who shared Bennelong’s room in the governor’s house, and was so easily duped into allowing him ‘French leave’ (wicked pun – not mine, the historian’s, though the quip was originally made by Captain Hunter in 1790). But I’m struggling to reconcile the dates of this incident with the historical record – something is awry in the timing, leaving me curious about the identity of the French cook whose ‘peculiarities’ Bennelong so mischievously teased. Or perhaps there has been a bit of historical ‘myth-interpretation’ afoot, either in Tench’s journal entry, or more recent historians’ interpretations.

![Banalong [Bennelong] Profile portrait of Banalong [Bennelong]](../../app/uploads/sites/2/2014/07/xwilliam-waterhouse-bennelong-1793-blog.jpg.pagespeed.ic.bb1qVkhD7k.jpg)

Banalong [Bennelong] by WW [William Waterhouse], c. 1793. State Library of NSW DGB 10, f. 13

2 + 2 = 5

Archival records state that ‘Bernard [de] Maliez, Servant to His Excellency’s Household’ died in Sydney on August 7, 1789. It appears Maliez had been quite ill as being ‘mindful of my mortality’ he took time to prepare a Will in favour of his mother, Mary Joseph Victorie Michell, of Lille, Flanders, France (now Belgium) on June 26th, 1789. The Will, held in the National Archives at Kew in England, is signed by Judge-advocate David Collins and Commissary Andrew Palmer, with a note confirming the date of his death, endorsed by Phillip himself.

The conundrum

So the glaring question is, how could Bennelong, who was not captured until November 1789, have spent any time with or around Maliez, to study and mimic his gait and mannerisms, when Maliez had been dead for over three months? If it was not Maliez that Bennelong was copying, who was the French cook in Phillip’s household that Tench refers to, during Bennelong’s residence at Government House? To date I have no answer, but I am advised that Fuzey Fombell, seaman on Sirius, was French, and so may be a contender, and other candidates may appear as inquiries proceed… All theories welcomed s’il vous plait!

Phillip 200 symposium

2014 marks the 200th anniversary of Phillip’s death, August 31, 1814. The life, achievements and legacy of founding governor, Arthur Phillip will be honoured at a series of commemorative Sydney Living Museums’ events http://sydneylivingmuseums.com.au/arthur-phillip-bicentenary

Sources and acknowledgements

I would like to thank specialist historian Michael Flynn for his assistance with my inquiries, verifying historical details and directing me to Maliez’s records.

Admiralty Records, National Archives, Kew, UK. ADM/48/60

Biographical Database Australia (BDA)

NSW Births, deaths and marriages register (NSW BDM)

The convict stockade a project of Scott Brown and History Australia. Sirius, 1788, entries 1512, 1513.

Keith Vincent Smith. Bennelong. Kangaroo Press. 2001

Thomas Kenneally. Australians: origins to Eureka. Allen and Unwin. 2009.

Original version of Rhodes’ Bennelong image held by Natural History museum, London.