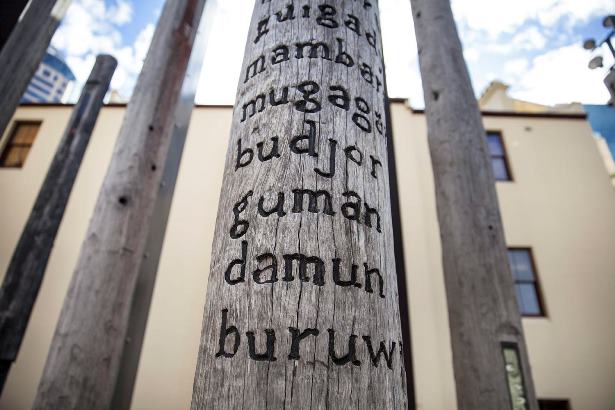

From the edge of the trees the Gadigal people watched as the strangers of the First Fleet struggled ashore in 1788. This installation by Janet Laurence and Fiona Foley symbolises that first encounter. Wander through trees embedded with materials and language evoking the layers of memory, people and place.

Museum of Sydney, built on the site of first government house, is in part, a monument to the commemorate first contact between British colonisers and Sydney’s Indigenous Peoples. The Edge of the trees art installation on the museum’s forecourt and interpretive displays in the museums help relate Aboriginal Peoples’ part in Sydney’s story – past and present, and NAIDOC week celebrations in Sydney continue to celebrate each year. Sydney Living Museums is hosting a NAIDOC open day at Rouse Hill House and Farm this weekend.

Fresh is best

Aboriginal peoples lived off the land and the waterways around Port Jackson for millennia, but British colonists brought their own established food culture with them, which had to adapt to this new and unfamiliar locale. Identifying viable food resources was quite a challenge to the newcomers, and there is a great deal of evidence in first fleet chroniclers’ journals about experimenting with native produce. As we’ve mentioned in previous posts, fish & shellfish, native birds and animals, wild greens, fruit and berries, offered welcome change from rationed salt-provisions, which were brought with the fleet from England. Native produce provided variety and freshness, and some were valued for their medicinal qualities.

Fish catch and Dawes Point, Sydney Harbour, John William Lewin, c1813. Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide. Gift of the Art Gallery of South Australia Foundation and South Australian Brewing Holdings Limited, 1989. Given to mark the occasion of the company’s 1988 centenary

While the two cultures often competed for the region’s food resources, there are many instances of active exchange and sharing of foods between Aboriginal people and colonists in extant records form the early settlement period. Of course we are limited to the colonists point of view, as it is their documented records that have survived the 225-odd years since European settlement, but it is important to recognise that efforts were made by both parties to establish positive cross-cultural relationships in the early years of settlement – many of them enacted with food.

British surgeon George Worgan noted in 1788,

[Aboriginal people] have a Generosity about them, in offering You a share of their Food.—If you meet with any of them, they will readily offer You Fish, Fire, & Water.

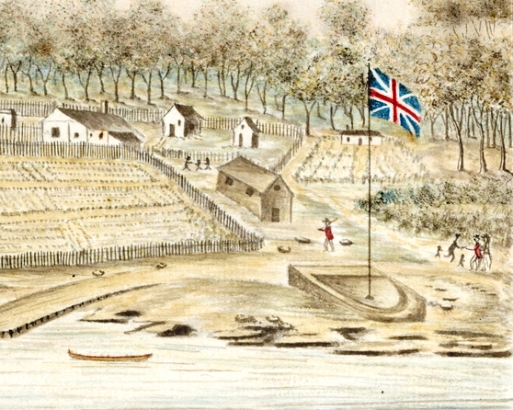

In the early 1790s, when food was scarce throughout the region, Aboriginal people frequently visited the Sydney settlement, camping in the governor’s compound (where Museum of Sydney now stands) or residing temporarily in the settlers’ huts,or in huts provided for local Aboriginal people to use. Meat, bread, rice and fish were given out or bartered.

Governor’s House at Sydney, Port Jackson 1791 (detail) by William Bradley. Note the greeting taking place in the right hand corner of the image. State Library of NSW Safe 1/14

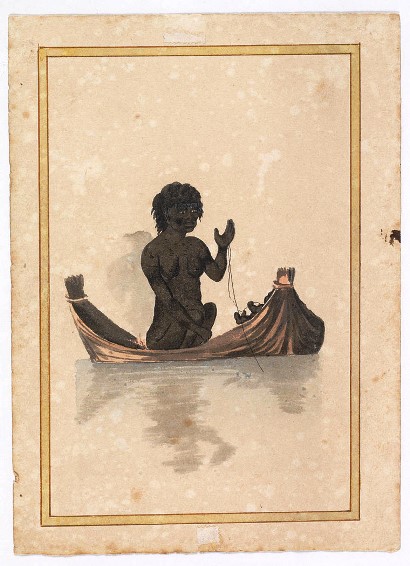

Governor Phillip ordered that Aboriginal people were to be given a portion of fish from each haul of fish caught in the colonists’ nets, but the trade worked both ways. An enterprising young Aboriginal man, Balderry, made regular runs to Parramatta in his canoe, to trade freshly caught fish on his community’s behalf. His business efforts were dashed when convicts damaged his canoe, and they were duly punished at the Governor’s orders. There are reports of Aboriginal women, who had intimate knowledge of fishing in the harbour, working with convict, William Bryant, the colony’s principal fisherman, directing him to the best spots to find fish.

Aboriginal woman in canoe fishing with a line attributed to George Charles Jenner and W.W. [William Waterhouse]. State Library of NSW DGB 10 f.11

Insider tips

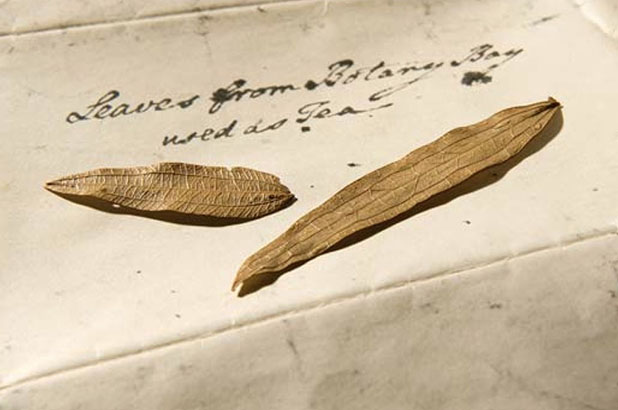

It is highly likely that colonists were advised on other native produce, such as the native herb, smilax glyciphylla, that the convicts and marines used as a substitute for tea leaves. The first fleet surgeons believed they were a cure for scurvy and other ailments, and although Aboriginal people did not use these leaves as an infusion, may have gained knowledge of their usefulness as a medicinal plant from the local Aboriginal people.

Gourmet secrets

Aboriginal people took pride in their food resources, and were obviously willing to share their favourite delicacies with the settlers. Watkin Tench seemed very appreciative of learning the delights of the harbour’s snapper, which due to the nub on the top of their heads reminiscent of the light infantryman’s helmet earned them the name of light-horseman-

At the top of the list, as an article of food, stands a fish, which we named light-horseman . The relish of this excellent fish was increased by our natives, who pointed out to us its delicacies. No epicure in England could pick a head with more dexterity than they do that of a light-horseman. Tench 1793.

And although Judge-advocate David Collins wasn’t so keen on some of the local bush foods, others were:

[They] indulge themselves with a delicacy which I have seen them eager to procure. In the body of the dwarf gum tree are several large worms and grubs, which they speedily divest of antennæ, legs, &c. and, to our wonder and disgust, devour. A servant of mine, an European, has often joined them in eating this luxury; and has assured me, that it was sweeter than any marrow he had ever tasted; and the natives themselves appeared to find a peculiar relish in it. Collins Account 1798.

This not only indicates shared knowledge but the sharing of a meal item which was highly prized in Aboriginal culture, and a willingness from the European settler to try culturally unfamiliar food.

Noel Lonesborough leads staff on the Bush Foods & Medicine Garden Tour, Boolarng Nangamai Aboriginal Art and Culture Studio. Photo Holly Schulte © Sydney Living Museums

NAIDOC open day at Rouse Hill House and Farm

We continue to be enriched and learn from Aboriginal people in our community, about their culture, including their foods, and NAIDOC week is a fantastic opportunity to enjoy the fruits of their knowledge and heritage. Join us at Rouse Hill House and Farm this weekend for a very special cultural exchange.