Nicola Teffer, curator of the Celestial City exhibition, is our guest blogger this week, giving us an insight into the ‘ladies who lunched’ in the late nineteenth century…

Sydney in the 1870s was no place for a lady. Not only were there no public toilets for women, the city offered few places where they could eat and drink. Pubs were off-limits, and cafes, oyster saloons and cigar divans were a bit too racy for girls keen to protect their good reputations.

For the men, of course, it was a different story

Sydney was a man’s town, “a city of men in bowlers and top hats” who eagerly awaited the 1pm church bells chiming the dinner hour.[1]. Businessmen enjoyed a “formal hot lunch of three courses – soup, joints, sweets, with cheese and salad to follow” at places like the Café Francais or the Café Restaurant while their working-class colleagues ate oysters, pies and fried fish from less salubrious oyster saloons [2]. Middle class ladies appeared in the city not to eat, but to shop or parade “their finery on the Block”, before presumably returning home for a comfort stop, a cup of tea and a good lie down [3].

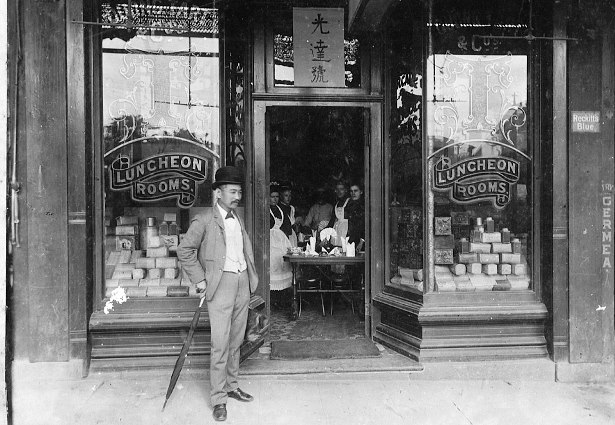

Quong Tart in front of tea rooms, possibly 777 George Street. Tart McEvoy Papers, Society of Australian Genealogists PR 6/26/14

Feminine appeal

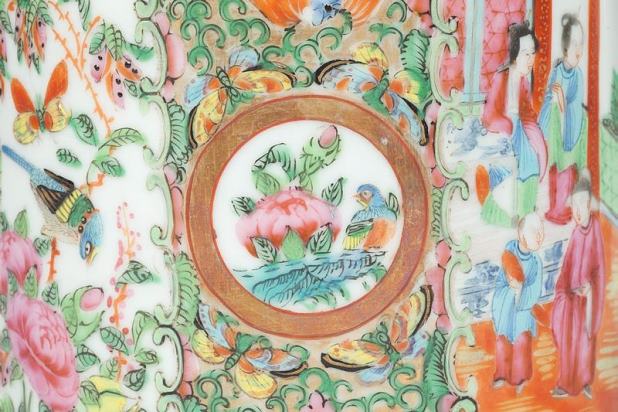

Quong Tart, the entrepreneurial proprietor of the tea rooms and former goldminer, struck a rich vein when he decided to market his business towards the women of Sydney, with lounges equipped with writing materials, magazines and “powder rooms”. You can almost hear the communal feminine sigh of relief with the news in 1881, that the Chinese tea-merchant Quong Tart was opening tea rooms, specially fitted out for ladies, in the new and fashionable arcades of Sydney. The Loong Shan Tea Rooms didn’t serve lemon chicken or anything in a black bean sauce – their menu was strictly British – but they differed from other restaurants in Sydney by welcoming women as both employees and patrons. Here, at last, were places where women could eat, drink (tea only of course – the cup that cheers, but does not inebriate!) and meet in the city. Women flocked to his tea rooms, entranced by their exotic Chinese carvings and aromatic tea served in delicately patterned porcelain.

Contentious issues

And it wasn’t just to drink the tea. Some women had more serious purposes in mind, such as the Women’s Literary Society (WLS) – a kind of ladies’ book club – that not only discussed the literary works of the day, but such contentious issues as the women’s vote. It was upstairs in the Loong Shan Tea Rooms in 1889 that a member of the WLS, Maybanke Anderson, raised the question of female suffrage, only to be countered by a much esteemed member of the group who angrily objected to the discussion of such a disgraceful matter.

Quong Tart inside the Loong Shan Tea rooms by Cleare and Co., Sydney. Tart McEvoy papers, Society of Australian Genealogists 11/6/6/26 no.7

Undeterred, Maybanke continued to meet at the Loong Shan with her fellow suffragettes, and there they planned the campaigns for the vote, for women’s rights, for kindergartens and equal pay. Without spaces like the tea rooms, in which women of all classes could gather in a central location, these first wave feminists would have faced not just the question of how to change national legislation, but the very basic problem of ‘where do we meet’? Sydney, with the help of a Chinese restaurateur’s business acumen, was changing to meet the needs of women and they seized the opportunity to ‘take over the joint’, to agitate for political reform and take their place in the social and political life of the city.

View of Loong Shan Tea House, 137 King St by Cleare and Co., Sydney. Tart McEvoy papers, Society of Australian Genealogists PR 6/26/10

Special thanks to Ralph Hawkins from the Society of Australian Genealogists who provided access to Quong Tart archives and resources.

[1] James Tyrell, Old Books, Old Friends, Old Sydney. Angus and Roberston, Sydney, 1952, 77.

[2] James Inglis, Our Australian Cousins, 1879, p.170.

[3] Tyrell, 77.