Can you just imagine light-footed dancers skipping across the governor’s table, mindful not to upset a glass or tread in anyone’s dinner…

“We yesterday dined at Government House, at a farewell dinner given to Colonel and Mrs Paterson. – It was but stupid – Mrs Macquarie has not the art of making people feel happy and comfortable around her. There were in all Seventeen Persons present[.] Mrs Ms dinners, are as much too small as the dinners usually given in the Colony are too profuse…

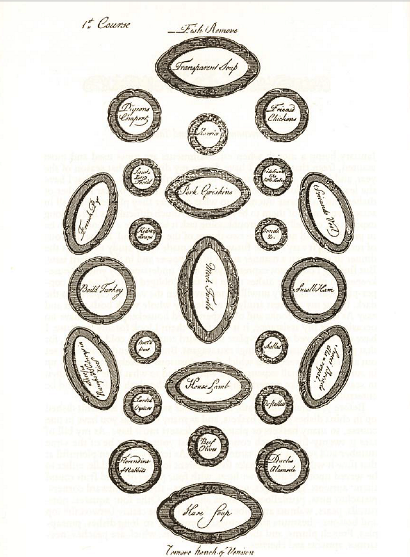

… At the Top (where Captain Antill, the aid de Camp presides) there was Soup removed by a very small Boiled Turkey at the Bottom (where Captain Cleveland the Brigade Major sits). There was a piece of Roast Beef. The sides were fricassee, curried Duck, Kidneys & a Tongue, the Corners Vegetables. 2nd Course, at the Top, Stewed Oysters, bottom Wild Ducks, sides & corners tartlets, Jellies & vegetables, in the middle there was an Epergne. – The Table was very large, & one might have danced a Reel between the dishes.”

Judge-advocate Ellis Bent to his mother, 27 April 1810.

Dancing to another’s tune

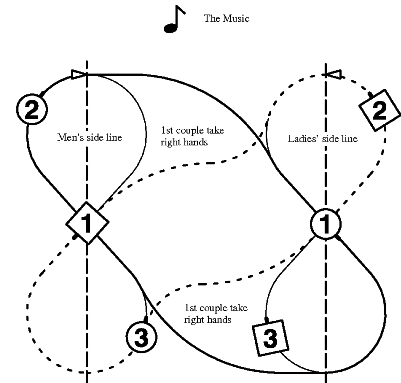

A reel is a Scottish dance, and as Jane Austen movies attest, were very popular in the Regency period.

Inveran Reels Figure, Scottish country dancing dictionary © Reuban Freemantle, 2014

James Cassidy, Professor of dance and author of A Treatise on the theory and practice of dancing 1810 gives an evocative description:

“One of the most pleasing movements in reel or country dancing which answers all the principles varying at once, is what they call the Hay [or heying]. The figure of it altogether represents a number of serpentine lines, interlacing or intervolving each other.”

A tough crowd to please

It seems as though Elizabeth Henrietta Macquarie had a long way to go to win over Sydney society. And while it may be ill-mannered to criticise one’s hostess, I am grateful to Ellis Bent for this little slice of edible history, which has survived for us to relish. This dinner follows the dining style of the day, a la Francaise, Regency style. Bent takes particular note of who sat where, which was terribly important and, of course, determined according to rank and professional importance (I wonder where Mr Bent was positioned?).

First course table plan illustrated in Elizabeth Raffald, The experienced English housekeeper, Southover Press, East Sussex, facsimilie of 1769 edition. Caroline Simpson Library and Research Collection, Sydney Living Museums 641.5942 RAF

A worldly palate

This menu is the earliest I have found that references a curry – duck on this occasion – being served in the colony. Although curries appear in English cookery texts from 1747, they were still very fashionable in the early 1800s. Certainly they were appearing on the finer tables in England – Mrs E’s letter to Maria Macarthur in 1812, which contained a selection of menus and advice on entertaining in polite society at the time, recommended various kinds of curry be served at formal and sociable dinners. Interestingly, curries were only ever served as a first course dish. Curry powders were advertised in the Sydney Gazette from 1814, so prior to that it may have been left to the head housekeeper to concoct one from a recipe or cookbook.

Bent makes no special mention of the duck curry, so we can presume that it was not a dish worthy of remark over any of the others; perhaps he possessed a worldly palate, to which curries were customary, or maybe he was just a difficult man to impress?

The Indian connection

Lachlan Macquarie had spent many years serving in India between 1787 and 1807, as a lieutenant in the 77th Regiment and later, lieutenant-colonel of the 73rd Regiment. His accomplishments were significant, seeing much active service in India and Ceylon (Sri Lanka), with time also spent in China and Egypt before returning to Britain in 1807 with intentions to marry Elizabeth Henrietta Campbell of Airds (1778-1835) who at 29, was 17 years his junior.

It is impossible to imagine that Macquarie was not well versed in exotic tastes, not least of which would have included curries in India. Indeed, on a return visit to England in 1803, having landed at Brighton, “he sat down at the Castle Inn to the most excellent comfortable English Dinner for the first time these 15 Years!” The inclusion of a curry on his Sydney dinner table was de rigueur at the time, but would also have acted as a reminder to those in company, of his successful career in the Indian sub-continent. George Jervis, Macquarie’s personal servant who accompanied the governor to New South Wales, was Indian, spending over 25 years in his employ, so we can expect that there was a level of authenticity to curries served at Government House at this time.

A “shabby” table

We would expect that the menu Bent described would have satisfied Macquarie’s idea of a ‘comfortable English dinner’ embellished with trendy Regency delicacies such as tartlets and jellies, which had to be set without refrigeration – possibly kept cool in government house’s cellars or suspended down a well. Despite their cheapness, local oysters, as previously discussed in this blog, were clearly acceptable on the governor’s table, and wild duck provided a game component as was customary, for a formal meal. But the comment I find most interesting is Bent’s swipe at Mrs Macquarie for meanness, a criticism she has found hard to shake in over 200 years: “Mrs Ms dinners, are as much too small as the dinners usually given in the Colony are too profuse.”

Derby porcelain “Japan” dish, c1800-1820, from Governor Macquarie’s dinner service, currently on public display in The Lachlan Macquarie Room, Macquarie University Library. Image courtesy Macquarie University

Reading the list of dishes served makes you wonder what else might have been on the table in a more ‘profuse’ colonial dinner? While Bent’s is not a fully comprehensive description of the meal, it seems that there were six or seven dishes at each course, with the possibility of a few more ‘sides’ unworthy of mention – butter, sauces or gravy dishes, lemon slices etc. Size and quantity are clearly wanting – the turkey was ‘very small’, “a piece of beef” suggests it was only a piece of something that could have been larger, and “a” tongue – how many was he expecting? Seventeen people is quite a cohort to feed, so perhaps the spread was a bit skimpy for one with a robust appetite. The Macquarie’s attracted other disparaging comments from colonists, Joseph Arnold noted in February 1810, “both Scotch & consequently close fisted… [the Macquarie’s] kept a shabby table”.

‘It is not genteel to crowd the table’

I’m not sure why I feel the need to defend Mrs Macquarie, but let’s consider the advice Maria Macarthur was given in the early 1810s by Mrs ‘E‘ her godmother in England,

“Many people do not understand the rules on these occasions… it is not genteel to crowd the table… it is not the fashion now to cram the guests, and force them [to] eat … at the same time, it is better to be civil, than to be censured as being rude, by those who do not understand new customs… we must conform in some degree to other peoples prejudices, and the custom of the society in which we reside…” Mrs ‘E’. 1812

These mealy-mouthed comments and negative accounts were made in the first few weeks and months of the Macquarie’s time in the colony. Without a helpful godmother to guide her, as young Maria Macarthur had in Mrs ‘E’, it seems Elizabeth Macquarie’s mistake was to abide her own sensibility rather than concede to local expectations- and she obviously had the locals reeling.

Sources and further reading

The governor’s table, Jane Kelso.

James P. Cassidy. A Treatise on the theory and practice of dancing. Dublin 1810; Reuben Freemantle, Scottish country dancing dictionary; Thomas Wilson. 1822. An Analysis of Country Dancing, Wherein All the Figures Used in that Polite Amusement are Rendered Familiar by Engraved Lines: Containing Also, Directions for Composing Almost Any Number of Figures to One Tune, with Some Entire New Reels; Together with the Complete Etiquette on the Ball-room. W. Calvert. 1822 (Google eBook); Life at Government House in the Macquarie era, Sydney living Museums; Macquarie University Journeys in time: Lachlan Macquarie. 2009; Lachlan and Elizabeth archive, Macquarie University library; The Lachlan and Elizabeth Macquarie room; Australian Dictionary of Biography – Ellis Bent, Elizabeth Macquarie, Lachlan Macquarie; Joseph Arnold to his brother, 25 February 1810, ML A1849/2, p3. Advice to a young lady in the colonies being a letter sent from Mrs E of England to Maria Macarthur in the colony of N.S. Wales in 1812 – Barca, ed. 1979.

Special thanks to Jane Kelso, historian for her research published in ‘Life at government House in the Macquarie era’ in Insites Historic Houses Trust NSW, 2010.