This Sunday marks the 250th birthday of one of Australian history’s most famous women – Elizabeth Macarthur!

Elizabeth’s character has always struck me as, to use a 19th century phrase, ’eminently sensible’. Throughout her life she displayed a philosophy that at times verges on the Stoic – Lennard Bickel called it a ‘habit of gentle acceptance’ [1], coupled with a determination and undoubted inner strength that she drew on at times of crisis throughout her life.

Every birthday needs a birthday cake!

We had a debate here about just what sort of cake was appropriate for Elizabeth’s birthday. We ummed and aahed about a fruit cake, certainly it would be historically appropriate for a special occasion, and would be a reminder of the abundance of fruit trees once grown at Elizabeth Farm. In the end a seed cake was the choice; well made from quality ingredients, not showy or flash but tasty and satisfying, and washed down with a good cup of Oolong tea. There’s an easy recipe for a seedcake below (including an even easier tip for a quick version). It seems appropriate for this colonial matriarch.

Elizabeth Veale was born in Bridgerule, Devon, on the 14th of August, 1766. Following the death of her father (when she was aged six) and her mother’s remarriage she moved first to her grandfather’s house, then to the care of the local vicar, John Kingdon, in his own household. In 1788 on the 6th October her life took a dramatic new course when she met and then married a young and ambitious officer then on half pay and living, and possibly teaching, in the area: John Macarthur. A small portrait in the State Library of NSW collection reputedly shows her around this time:

Elizabeth Macarthur (reputedly) ca1785 – 1790. State Library of New South Wales collection: DL Pa 8

Off to New South Wales!

And a dramatic turn it certainly was. Elizabeth was already 4 months pregnant, and had her first child, Edward, while en route to London in March the following year where John was transferred to the newly formed NSW Corps. Her new life was about to take her far from rural Devon, to the other side of the world.

She wrote philosophically to her mother that:

You will be surprised that even I who appear timid and irresolute should be a warm advocate of this scheme. So it is, and believe me I shall be greatly disappointed if anything happens to impede it. I foresee how terrific and gloomy it will appear to you. To me at first it had the same appearance, while I suffered myself to be blinded by common and vulgar prejudices. I have not now, nor I trust shall ever have one scruple or regret, but what relates to you… if we must be distant from each other, it is much the same whether I am two hundred, or far more than as many thousand miles apart from you. The same Providence will watch over and protect us there as here. The sun that shines on you will also afford me the benefit of his cheery rays.

1st September 1789

After a disastrous voyage that saw her husband fight a duel before they’d even raised anchor and then nearly die of an unknown fever, and, worse, a daughter born prematurely and buried at sea, Elizabeth and her family arrived at Sydney town. A few years later in 1793 they moved to their new home, a newly built brick cottage near Parramatta on the 100 acre estate named after her – ‘Elizabeth Farm’. Though she cannot have known it, the tumultuous events of her life had only just begun.

‘At the Elizabeth Farm’

We know a great deal about the lives of the Macarthurs and goings-on in the early colony because of Elizabeth’s letters and journals. These in turn form only a part of a colossal archive known as – take a guess! – the Macarthur Papers, held in the State Library of NSW; you’d be hard pressed to find a history of the colony that doesn’t at some point quote from them. Importantly, they have been a constant source of information for ‘history from below’, the move away from history being dominated by the study of leading (typically male) figures. The study of the servant’s lives at Vaucluse House, Elizabeth Farm and Elizabeth Bay are prime examples. Women’s histories are a significant part of this, and Elizabeth Macarthur’s life with its wealth of documentary material has been a source of fascination for decades.

Readers of this blog will be familiar with quotes from Elizabeth, on topics ranging from the content of the estate’s kitchen garden, to what time the Macarthurs ate their meals, the supply of bread rolls and the never-ending attempts to grow capers: “We have made a small quantity of olive oil, and we have had capers for our mutton. We cannot find out a successful mode of propagating the caper plant. I fear ours is a peculiar variety.” [2].

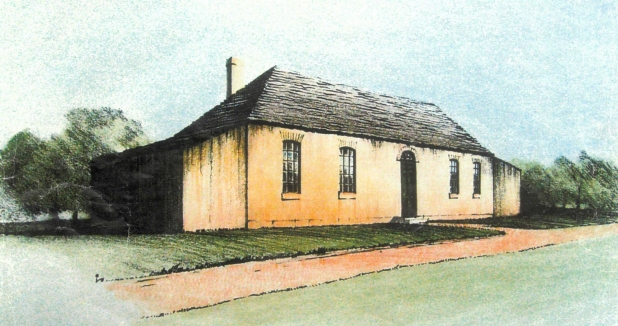

Elizabeth Farm as it may have appeared in 1793. Image (c) Sydney Living Museums

She wrote of the prosperity of the estate, located on the floodplain of the Parramatta River and for several years the proverbial food-bowl of the colony:

I thank God we enjoy all the comfort we could desire, but to give you a clearer idea of our present situation I shall make free to transcribe out of a letter of Mr MacArthur’s addressed to his brother: ‘The changes that we have undergone since the departure of Governor Philip are so great and extraordinary that to recite them all might create some suspicion of the Truth. From a state of desponding poverty, and threatening famine, that this settlement should be raised to its present aspect, in so short a time is scarcely credible. As to myself – I have a farm containing nearly 250 acres, of which upwards of 100 are under cultivation… Of this year’s produce I have sold £400 worth, I have now remaining in my granaries upwards of 1800 bushels of corn. I have at this moment 20 acres of very fine wheat growing, and 80 acres prepared for Indian corn and potatoes with which it will be planted in less than a month. My stock consists of a horse, two mares, two cows, 130 goats and upwards of 100 hogs. Poultry of all kinds I have in the greatest abundance….’

The next line is one of our favorites, as it details the transition of native foods to the colonial table. This came with a sting though – with guns and hunting dogs the European population quickly exhausted the traditional food source of the existing Indigenous population.

With the assistance of one man and half a dozen greyhounds, which I keep, my table is constantly supplied with Wild Ducks or Kangaroos averaging one week with another, these Dogs do not kill less than 300 pounds worth. The house is surrounded by Vineyard and Garden, about 3 acres. The former full of vine and fruit trees, and the latter abounding with the most excellent vegetables… [3]

We enjoy here one of the finest climates in the world, The necessities of life are abundant, and a fruitful soil affords us many luxuries. .. We have at this time about 120 acres in wheat all in a promising state. Our gardens, with Fruit and Vegetables are extensive and produce abundantly. It is now spring and the eye is delighted with the most beautiful variegated landscape. Almonds, Apricots, Pear and Apple trees are in full bloom. [4]

Elizabeth Macarthur. State Library of New South Wales collection: DG 221

Elizabeth Farm was to be her home for the rest of her life, and during her husband’s long years of exile – first following first a duel with his commanding officer, and then his pivotal role in the overthrow of Governor Bligh – it was from here that she oversaw her household, her husband’s estates, and the development of the merino wool flocks on which the family’s fortunes would later rest. While she was not alone in this, having assistance from various Governors and John’s nephew Hannibal, and with a barrage of letters giving instruction form her husband, her achievements were considerable. The only time she left Parramatta for more than a temporary visit was during the whole-scale renovations to Elizabeth Farm from 1826, and then when her husbands deteriorating health made it impossible for her to stay.

Elizabeth Macarthur aged 79, in 1945. Portrait from Camden Park reproduced as the frontispiece of Sibella Macarthur Onslow’s (1914), ‘The Macarthurs of Camden Park’.

She returned to Parramatta after his death at Camden, and lived there at “dear ancient Parramatta”, as she called it, for another 26 years. She died in 1850, aged 84, while visiting her daughter Emmeline and her husband Henry Parker at their house ‘Clovelly’, at Watson’s Bay. She was buried at Camden Park in the family mausoleum, survived by five of her nine children.

A copy of Elizabeth’s portrait hangs in the vestibule of Elizabeth Farm today. Photo (c) Leo Rocker for Sydney Living Museums

Seedcake

Ingredients

- 2 eggs

- 1/2 cup sugar

- 125g butter, melted

- 1/2 teaspoon vanilla

- 125g self-raising flour

- 1 tablespoon caraway seeds

Note

Seedcakes, flavoured with caraway, were popular fare throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, fading from glory in the early 1900s. If you don't want to make a cake from scratch (although this is a very easy recipe), you can do what my friend Jemma's grandmother did – simply add a tablespoon of caraway seeds to a store-bought sponge or butter cake mix!

Directions

| Preheat oven to 180ºC and grease and flour a loaf tin. Beat the eggs and sugar together until pale and frothy. Add the butter, vanilla, flour and seeds, and mix well. Pour batter into tin and bake for 35–40 minutes or until the top of the cake is golden and a skewer tests clean. Allow the cake to cool slightly in the tin, then transfer it to a cooling rack. Slice when cold. | |

Notes

[1] Lennard Bickel (1991), Australia’s first lady: the story of Elizabeth Macarthur, p9

[2] Elizabeth Macarthur writing to her son Edward in England, 12th may 1832. ML A2906

[3] Elizabeth Macarthur to Miss Kingdon in Bridegerule,, 23 August 1794.

[4] Elizabeth Macarthur to Miss Kingdon in Bridegerule, 1 September 1798.

Print recipe

Print recipe