Recently we celebrated the Elizabeth Farm Spring Harvest festival. It was a great day of artisan food, talks and demonstrations, and lazing about in deckchairs. In the dining room we looked at one of my favourite topics – historic table settings – and visitors had a go at creating a table setting that evoked a dinner with the Macarthurs.

The Cook and the Curator at the Spring Harvest Festival at Elizabeth Farm. Photo © James Horan for Sydney Living Museums

Setting the scene

We imagined it was a spring evening in 1829. ‘At home’ were John and Elizabeth Macarthur and two of their daughters, Emmeline and Elizabeth Jnr., and son William who was visiting from Camden (his brother James was at that time in England on business. In the diagrams below however I’ve used 6 settings to simplify the discussion). It was about 5pm, the family were just about to enter the dining room so the staff under the eye of the butler John Butler (yes, that really was his name!) were finishing the table. Like many well-to-do colonial families the Macarthurs ate their main meal slightly later in the day, about 5 pm. Their staff had already eaten at about 4. Breakfast, which was a substantial affair, was around 10:30 or 11am. By this stage all had been up for several hours. (A midday luncheon was still a meal for the future, when dining habits had changed significantly.) We then discussed the principles of the a la Francaise setting: that the various dishes were placed on the table and that diners served themselves and their fellow diners.

Whats on the menu?

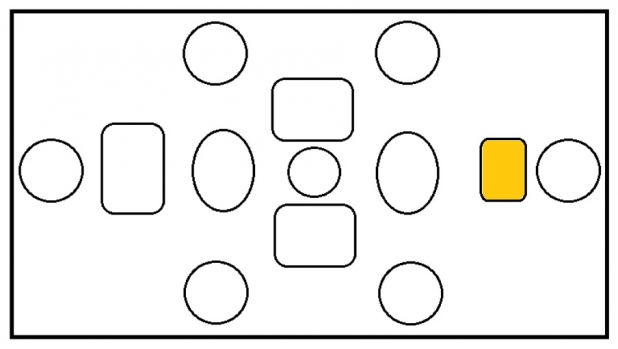

We used descriptions of colonial dinners by Godfrey Mundy and the later Macleay menu as a guide; kangaroo tail soup was also added, reflecting a letter written by Macarthur where he mentions hunting kangaroo with his greyhounds. The soup was placed (in yellow, below) ready in front of Elizabeth, along with a stack of soup bowls. She served it, and then it was taken around the table, possibly by the (then 24 year old) footman John Bono.

Location of the soup tureen in the first course of an ‘a la Francaise’ setting

If you thought Elizabeth Farm was a very mono-cultural place guess again: John Bono was described in official documents as a ‘Mussalman’, an archaic term for a Muslim. We know frustratingly little else about him; aged 15, had ‘arrived free’ in 1820 on board the ship the ‘Active’ – one of several to bear that name. As children James and William had been tutored by a French aristocrat, Gabriel Louis Marie Huon de Kerilleau; in the early 1820s there were also a Chinese cook, and a carpenter variously known as ‘Matchiping’ or ‘Mak Si Ying’ worked at both the main residence and nearby Hambledon cottage – and lets not forget the Greek pirates! Importantly, there was also a close association with Aboriginal people both from the local Parramatta area and the Cowpastures to the South-West, most notably Tedbury, son of the famed Pemulwuy.

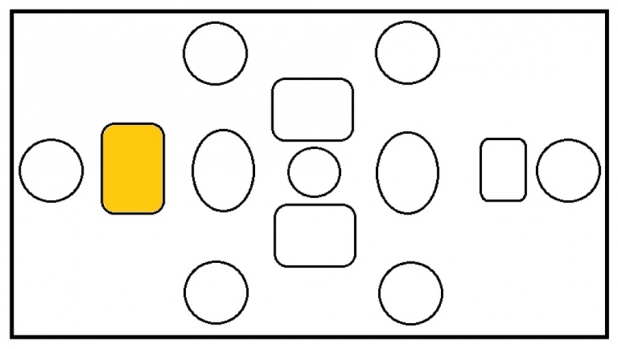

But back to dinner! At the other end of the table, in front of John (left of the diagram) , sits a large snapper served in a lemon sauce. This dish is also called a ‘remove’ because, quite literally, it will be removed when finished and replaced with another dish, in this case a meat dish of ‘beef tongue in a sauce piquante’ – a dish from the Macleay menu.

Location of the first ‘remove’ dish in an a la Francaise setting

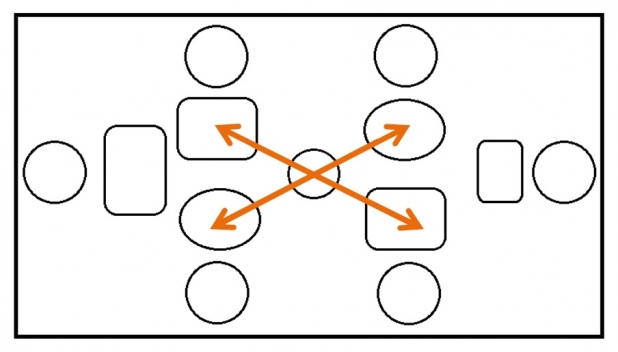

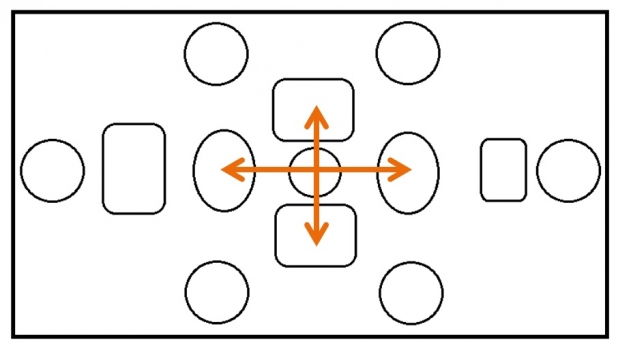

The soup and fish / beef tongues ‘answer’ each other. By this we mean that the positions they occupy on the table relate to each other in a geometric manner – in this case at opposite ends of the table’s central axis. The remainder of the dishes were a lettuce salad, cauliflower au gratin, Wonga pigeon in a bread sauce (which reminded Mundy he was “dining in the Antipodes”) and a ‘raised pie’. These were also arranged to ‘answer’ each other; with 4 dishes there are different ways they could be arranged, in a square or a diamond. The arrows show which dishes ‘answer each other’, the pigeon to the raised pie, the salad to the cauliflower. This way each diner had a combination of meat and vegetable / salad dishes in front to them:

Table arrangement showing the dishes ‘answering’ each other in the first course of an ‘a la Francaise’ setting

Another table arrangement showing the dishes ‘answering’ each other in an ‘a la Francaise’ setting

At the center of the table is a comport (we used two) of fresh fruit. You may remember Elizabeth’s description of the wide variety of fruit available at Elizabeth Farm:

In our own Garden, which is large we have Oranges, Lemons, Olives, Almonds, Grapes, Peaches, Apricots, Nectarines, Medlars, Pears, Apples, Raspberries, Strawberries, Walnuts, Cherries, Plums. These fruits you know. Then we have the Loquat a Chinese Fruit, The Citron, the Shaddock, the Pomegranate, and perhaps others that I may have forgotten to enumerate, such as the Cherry, and Guava. We have an abundance, even to profusion, in so much that our pigs are fed Peaches, Apricots & Melons in the Season. Oranges and Lemons we have the whole year round, yet there is a particular Season from May to August (our winter) when the Trees yield a regular crop. I have, I perceive, omitted to mention the Fig of which we have many varieties and an abundance. [1]

Dining table set during a talk at the Elizabeth Farm Spring Fair. Photo © Scott Hill for Sydney Living Museums

While also discussed the second course in large meal – where the dishes were replaced with a new set, and the gymnastics of the dessert where the table was stripped to the bare wood and reset. You can read about that course, and the Macarthurs dessert ware (and what they ate for breakfast), in this previous post.

Notes

[1] Elizabeth Macarthur writing from Parramatta to her childhood friend Eliza Kingdon in England, March 1816, ML A2908

What do we use when setting the table? While these are largely ‘prop’ items, they are sympathetic to the period we set out to evoke, namely the 1820s.

The silverware we use is 20th century, in ‘King’s pattern’ which was a popular design in the 19th century and indeed still today. The notable difference is the knives, which are today made in one piece; the Macarthur’s knives were made in two sections, a handle and a blade which was set into it. As a result, the knife was significantly heavier than its modern counterpart. Other silver serving-ware is from various dates over the early 20th century but is also sympathetic to the colonial period. The plates and serving dishes are modern Spode, but in a pattern called ‘Italian Landscape’ which dates to 1818. Glassware is crystal, and in a thumb-cut pattern also used in the 19th century. The ‘mallet’ design decanters however are late Georgian in origin.

Erratum

The original version of this post suggested that John Bono was “likely of South Indian” origin. Re-examination of the evidence doesn’t support this, meaning his origins are still unknown. Ongoing research may uncover more details, and we’ll update this should more become known.