While we’re on the subject of spices, this week I’m headed down the garden path to look at the decorative qualities of this culinary icon, ginger.

Down the (sub-tropical) garden path…

Edible ginger – also known as common, stem, true or ‘Canton’ ginger – was recorded growing in the colony in 1803 [1], and in the Botanic Gardens in Sydney in 1823, though it was not a great success and in 1827 Charles Fraser reported its condition was, unsurprisingly, ‘delicate’. Valued as a culinary and medicinal spice it was one of many plants being trialed – along with tea, coffee, cocoa, sugarcane and any number of grain crops – to see if a local industry could be established. While edible ginger clearly wasn’t a success, Sydney being just that bit too far (actually way too far) south, the many decorative and hardier forms were widely grown in shrubberies and pleasure gardens for their aesthetic and botanical novelty value.

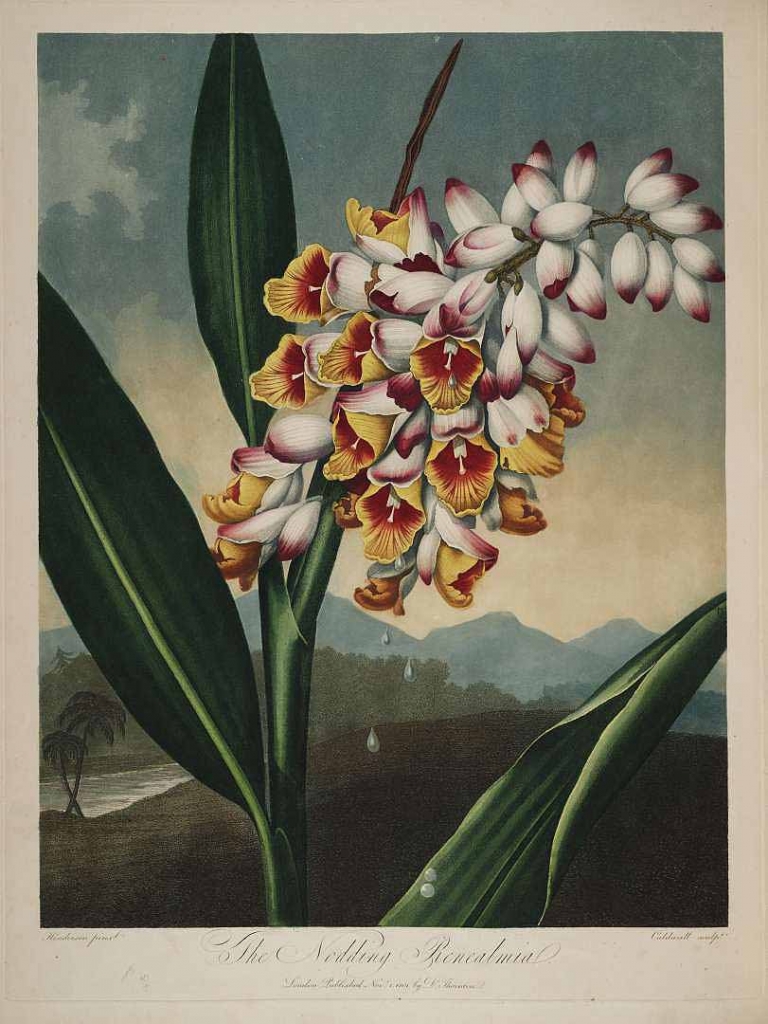

A particular favourite was the shell ginger, Alpinia zerumbet (then known as Alpinia nutans, and previously Renealmia nutans, as seen in Thornton’s plate below), named for its pendulous racemes of pretty, white ‘shell’ flowers flushed with yellow and pink. In the 1850s it was readily available from the various nurseries. At Vaucluse House we grow a stand of the variegated form (not surprisingly called A. zerumbet ‘Variegata’), whose leaves are striped with yellow and which likes to bake in full sun. Planted next to the bridge between the house and tearooms, its long stems – well over 10 foot high – create a decorative archway through which the house itself is first seen.

‘The nodding Renealmia’ (Alpinia zerumbet) from Dr Thornton’s ‘Temple of Flora’, 1807. Image www.archive.org

The white ginger – also known as the ”white garland-lily’ or ‘ginger lily’ (Hedychium coronarium) with its pure white flowers was also grown. Not actually a ginger at all, but named for the similar appearance of its arching stems and leaves, is the vivid ‘blue ginger’, (Dichorisandra thyrsiflora) seen here growing around shoulder-height in dappled light in the shrubbery at at Elizabeth Farm:

Blue ginger (Dichorisandra thyrsiflora) at Elizabeth Farm. Photo (c) Scott Hill for Sydney Living Museums

Gardeners today have a wealth of these flowering gingers to choose from, gathered from across south-east Asia, Micronesia and the Pacific Islands.

In the late 1800s garden style began to swerve significantly away from the Victorian gardenesque, and perennial plants grown for the quality of their foliage rather than their flowers became increasingly popular. With the proliferation of stove or hot-houses, characteristic broad-leafed tropical plants were able to be grown in climates far colder than their origins. Writer-designers like the Englishman William Robinson promoted this new style in his works including ‘The Sub-Tropical Garden, or, beauty of form in the flower garden‘ (1871). Whereas in England tougher plants such as yuccas and pampas grass were used to create the desired effect, in colonial gardens there were the many exotic gingers, philodendrons and crotons, cannas and bananas and so on all readily at hand.

Ginger’s cousin, cardamom

Also in the ginger family is the ‘Queen of spices’ cardomom (Elettaria cardamomum), one of the signature tastes and scents of, amongst many others, Indian and Sri Lankan cuisines. Medically it features alongside cloves used as a tincture, added to mouthwashes and antiseptics. Unlike the familiar ginger rhizome, it is the cardomom seed pod that is used. Kew Gardens website notes that “Cardamom is the world’s third most-valuable spice by weight (after saffron and vanilla)” and has the title ‘Queen of spices’, with pepper being the King. [2]

Green cardamom pods. Image: Prathyush Thomas, Wikipedia. Used under creative commons license.

Along with edible ginger, cardamom was grown in the colony quite early, also a plant recorded at the Botanic Gardens in 1827. Its leaves, carried on stems up to a towering six meters high, are a plain green. Its flowers are also white, but with a violet-tinged throat. The characteristic elongated seedpods grow in a bundle of three.

And here’s the catch…

Several species of cardamom are used to produce the edible pod; and what is often thought to be cardamom and frequently sold as such in nurseries is actually ‘false cardamom’, a dwarf variety of shell ginger (alpinia nutans). Its flowers are a lovely white with throats flushed with yellow and marked with orange/red.

A spike of ‘false’ cardamom flowers. Photo (c) Scott Hill, 2016

The colourful throats of individual ‘false’ cardamom flowers. Photo (c) Scott Hill, 2016

Sydney is too far south for cardamom to set seed and usually even flower, and false cardamom can be a no-show for flowers as well; along with our garden team we all noticed that the very warm summers we’ve been experiencing lately have resulted in a lot more flowers than usual, and even the round seed pods forming quite freely (true cardamom pods are more elongated). These were growing this past summer in my own backyard, Id never seen them flower let alone set seed in a decade, and had only grown them for their lush tropical appearance:

Cardomom seed pods. Photo (c) Scott Hill

Seeds aside, the leaves of the false cardamom are still very fragrant, simply run a leaf between your fingers or crush one to release the wonderful aroma. A favourite technique of mine is to wrap chicken or fish in a leaf (bruised first to release the scent) then in foil before roasting, barbecuing or steaming. Instead of adding cardamom pods to cooking rice, crushing one leaf into a small ball and popping it into your rice as its cooks will also impart a delicate flavour – its just a bit fiddly to fish out afterwards before serving.

And for dinner…

This easy 1885 recipe, from the Riverine Grazier, is for a dry curry using cardomom pods. I’m not quite sure I’d be trusting prawns transported that far inland in 1885 however! Some thinly sliced chicken would substitute; and assuming the recipe uses school prawns, which aren’t large, probably around 300 grams. The curry powder? A good Madras mix of course, and I’d add the pods to the onion as it fries to release the flavour, before adding the apple which Id grate just before use. Recently I’ve taken to quickly frying my rice in some ghee before I add the water; in which case pop 2 or 3 pods in there as well to create a scented accompaniment.

A Dry Curry.

— Two ounces of butter, one tablespoonful of curry powder, one small, onion, one small apple, two cloves, a pinch of cinnamon powder, a few cardamom seeds, two dried and powdered bay leaves, the juice of half a lemon, salt to taste, about one gill [now there’s a measurement you don’t see every day – use around 120 mls] of good stock, two dozen prawns. Melt the butter and fry the onion, apple, and curry powder for about five minutes ; add the stock and other seasonings and stir until boiling. Shell the prawns, add them to the sauce, and let simmer for ten minutes. Bo very careful not to add too much stock, as there should be no gravy [excess liquid] when the curry is served, but each prawn should be coated with a thick curry mixture. Served with boiled rice quite hot.

The Riverine Grazier; Ladies’ Column for Saturday, 12th Sep 1885

Notes

[1] ‘List of Plants in the Colony of New South Wales that are not Indigenous, March 20th 1803’

[2] Read more on true cardamom at the Kew gardens website: http://www.kew.org/science-conservation/plants-fungi/elettaria-cardamomum-cardamom

I also came across this article from 1882, promoting the cardamom plant for Queensland growers:

“Many of our (Queenslander) readers up North evince a desire to make the acquaintance of the cardomom, a tropical plant cultivated in India and elsewhere for its aromatic tonic seeds to be found amongst the stock of chemists and druggists everywhere. The name cardamom is generic, and applies equally to the seeds of Elettaria cardamomum and Amomum cardamomum, and these, besides being useful medicinally, form an important ingredient in curries, sauces, and the like. The former of these is a native of the tropical parts of India, and furnishes the small or Malabar cardamoms of commerce. The plant springs up spontaneously in the forests of Travancore when the land is cleared, and in four years’ time is matured and bears, continuing , to do so until the seventh year, when it is cut down, and makes a fresh start from the stump without any replanting. Amomum cardamomum is very similar to the above, the chief difference being in the flower, and both are members of the ginger family, Zingiberacea. Seeds of both varieties and several others known to commerce can be obtained from Indian planters and nurserymen, but, the plant being bulbous, the seeds will not readily germinate, so that plants or bulbs are more frequently used for making a plantation. After the plants are fairly started they are easily propagated by the shoots or suckers which arc thrown out from the root. In rich moist lands in Northern Queensland this plant should be readily established, and prove a valuable addition to our marketable products.” Brisbane Courier 23 December 1882