In the winter months, you’ll see them dangling from the branches of a tree at the bottom of the kitchen garden at Vaucluse House, by the compost heap, like bright baubles. These days, the shaddock (also known as pomelo or pumello) is less well-known than oranges and grapefruit. But in colonial Australia, this outsized citrus was a thing of wonder.

In high perfection and in great abundance

Shaddocks crop up in the histories of several Sydney Living Museums gardens – a sure sign of their popularity. In 1816, Elizabeth Macarthur wrote a letter to a friend back home describing them growing in her garden at Elizabeth Farm, Parramatta:

Our climate is delightful, and we have in high perfection and in great abundance the fruits of warm and cold climates. In our garden, which is large we have Oranges, Lemons, Olives, Almonds, Grapes, Peaches, Apricots, Nectarines, Meddlars, Pears, Apples, Raspberries, Strawberries, Walnuts, Cherries, Plums. These fruits you know. Then we have the Loquat, a Chinese fruit, the Citron, the Shaddock and the Pomegranate, and perhaps some others that I may have forgotten to enumerate, such as the Cherry and Guava.

In England, shaddocks could only be cultivated with the aid of expensive and elaborate hothouses or orangeries. Like many colonists, Elizabeth was thrilled to find that Sydney’s temperate climate meant that they and other exotic fruits could be grown here with comparative ease.

Big as a man’s head

‘The shaddock tree’, The Ladies’ Garland, volume 5, p. 264, Philadelphia, J Van Court, 1842

Shaddocks are the largest of the citrus fruits and can grow to staggering proportions in their native south and south-eastern Asia, where they are an important part of the Mid-Autumn Festival. Sir Hans Sloane, whose collections would later found the British Museum, encountered them on his trip to Barbados in 1687 and marvelled at their prodigious size:

This Tree is in every thing like an Orange-Tree only larger … The Fruit is round as big as a Mans Head. The Rind is yellow and smooth, not thick, and the Pulp is very Aromatick besides it has a sweetish sour Tast.

At Vaucluse House, the shaddocks never grow anywhere near this big!

Sloane also gives an explanation for the name: the shaddock was brought to Jamaica by a Captain Shaddock, a commander of the East India Company, en route to England. (Subsequent research has tied this legend to an actual historical figure, Philip Chaddock.) There, they hybridised naturally with a sweet orange to give us the grapefruit.

A Rouse Hill recipe

At Rouse Hill House and Farm, a handwritten recipe for shaddock jam was found tucked into an old cookbook that had belonged to Nina Terry (nee Rouse, 1875–1968). The hand isn’t readily identifiable, but the recipe may have been written out by Nina herself. Her granddaughter Miriam Hamilton recalled Nina hosting afternoon teas in the garden, continuing a long family tradition.

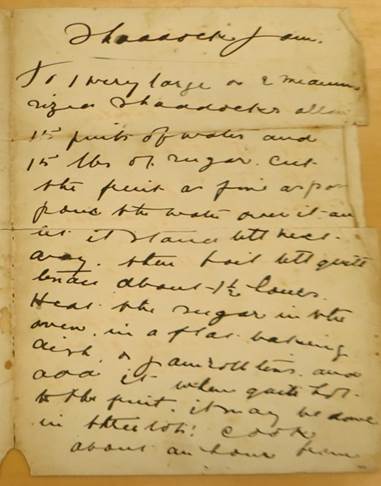

Recipe for shaddock jam, date unknown. Rouse Hill House & Farm collection, Sydney Living Museums R89/70-1:3

The recipe’s proportions indicate both the size of the fruit and the thickness of the rind: just one very large shaddock (or two medium-sized ones) to a whopping 15 pounds (7 kilos) of sugar! Shaddocks can grow to weigh several kilos. Nonetheless, these were either very strongly flavoured shaddocks, or the taste was for very sweet jam.

Written by hand

Interestingly, a near-identical version of the Rouse Hill recipe appeared in several NSW newspapers in the winter of 1908, accompanied by a simple recommendation: ‘This is excellent.’

Perhaps Nina, or whoever the scribe was, had a glut of shaddocks and was looking for ways to use them; she may have copied the recipe from the newspaper. The ‘untidy hand’ suggests it was written in a rush – Jacqui and I had to pore over certain words to make sense of them.

Shaddock blossoms in the kitchen garden at Vaucluse House, September 2015. Photo by Helen Curran © Sydney Living Museums

In these lazy late-modern times, I’m more likely to get out my phone to snap a picture of a recipe I’d like to try. Looking at that sloping hand reminded me of my father’s mother, a legendary baker, whose suitcase would always be filled with baked treats when she made the road trip from Invercargill to Dunedin, in New Zealand’s far south, to see us. Her recipe book – like this recipe for shaddock jam, tucked into a favourite cookbook alongside recipes for mustard pickles and meat soufflé – was written by hand.

Shaddock jam … a perfect companion to one of Nana’s famous scones.

Shaddock jam

To 1 very large or 2 medium sized shaddocks allow 15 pints of water and 15 lbs of sugar. Cut the fruit fine as poss. Pour the water over it and let it stand till next day. Then boil till quite tender about 1½ hours. Heat the sugar in the oven in a flat baking dish or jam roll tins and add it when quite hot to the fruit. It may be done in three lots. Cook about an hour from the time the first lot of sugar goes in.

—Helen Curran is an assistant curator at Sydney Living Museums.