Looking for a quintessential 19th-century meaty stew for a recent Colonial gastronomy program, ‘Butcher, baker, candlestick maker’ held at Susannah Place Museum and The Big Dig site in Sydney’s Rocks, we decided on the traditional ‘Haricot Mutton’.The haricot bean immediately springs to mind, but surprisingly, they do not feature in the traditional recipes for the dish. The key characteristics of this humble stew are instead, mutton or lamb neck chops, cooked with onions, carrots and turnips.

If at first you don’t succeed…

To modern tastes the recipe seems decidedly ‘plain’ – the only added flavours being salt, pepper and in some ‘fancier’ versions, a sprig of thyme or a flourish of Worcestershire Sauce upon serving. As the program was being held at Susannah Place it seemed fitting to use Dolly Youngein’s school cookery homework book (see below), but when first tested, the dish was disappointingly bland in flavour, and I popped it in the fridge knowing I’d have to find an alternative ‘classic’ to serve on the day.

Turnips in Beeton’s book of Household management, 1863. Rouse Hill House & Farm Collection. Sydney Living Museums

The missing ingredient

Never one to waste good food, Dolly’s haricot mutton became family dinner a couple of nights later with some mashed potato and crusty bread, served with an apology from being a bit dull. While tempted to boost it with a choice of condiments – mustard, horseradish and the like, we tried it on its own merit to see which might complement it best, but the flavours had developed over the weekend, into a dish with a great deal more character than when first taken from the oven. The turnip, a vegetable which I’m not terribly fond of, for its slightly acrid edge, had added something quite special to the meat and gravy, the carrot tempering some of the bitterness, with its earthy sweetness. No additives required – all it needed was time!

Haricot mutton on the table at Susannah Place Museum. Photo Jacqui Newling © Sydney Living Museums

What, no beans?

Recipes abound for Haricot mutton in cookbooks in the 1800s – in fact I’d challenge readers to find a cookbook without one, but the dish was well entrenched in English cookery by this time. It has been suggested that the dish is so old, that the haricot bean took its name from the one-pot slow stewing process that the haricot mutton shares. Cookbooks aimed at upper middle classes include haricot mutton recipes, suggesting that it wasn’t just a peasants’ dish, even though neck chops are an economical cut of meat.

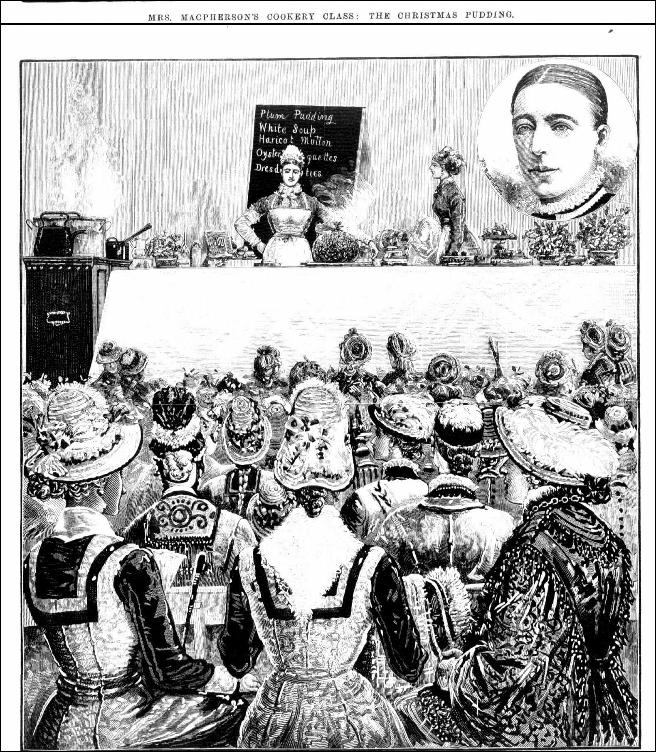

Mrs Macpherson’s Cookery Class, The Australian Sketcher, December 20, 1879. accessed via TROVE, National Library Australia.

A life’s lesson

‘Haricot Mutton’ is one of the recipes featured in an illustrated depiction of Mrs Emily Macpherson’s cookery class in 1879, shown above. Thinking gastronomically, could mean two things: that it (like the other familiar dishes listed in the program such as Plum Pudding, white soup, Oyster Croquettes) was such a popular and necessary dish that all cooks needed to know how to make it, or, that the illustrator is having a bit of a crack at Mrs Macpherson’s students, for needing to be taught such staples. Personally I think it is the latter…

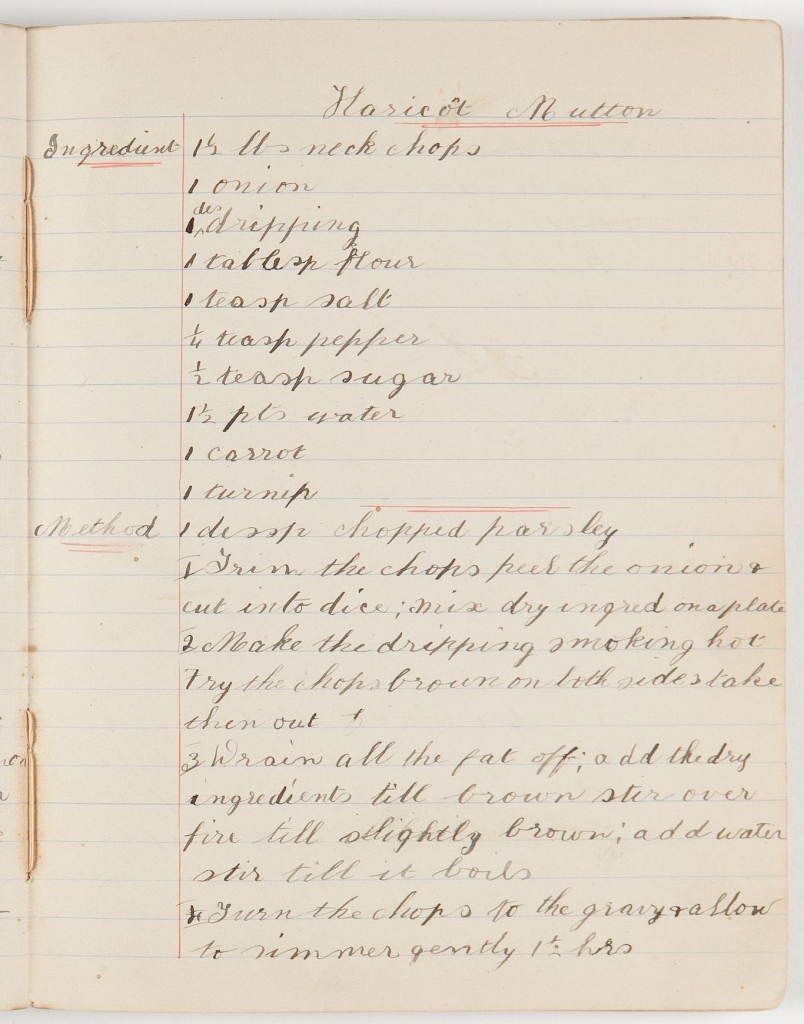

Recipe for Haricot Mutton (p. 1) from Dolly Youngein’s cooking homework book, Fort Street School. Courtesy John Brown. © Sydney Living Museums

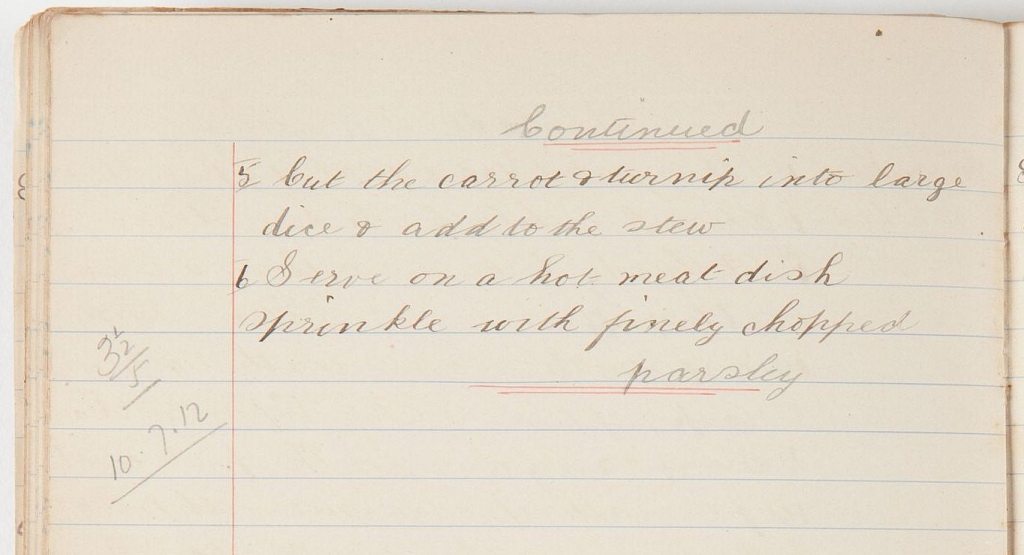

Recipe for Haricot Mutton (p. 2) from Dolly Youngein’s cooking homework book, Fort Street School. Courtesy John Brown. © Sydney Living Museums

School-book staple

‘Haricot Mutton’ is also on of the dishes that twelve year old Dolly Youngein was expected to master as part of the Plain Cookery course she undertook at Fort Street Public School in 1912. Dolly’s work did not score well in her homework book, losing 30% of her mark – possibly for the omission of adding the onions to the pot when the browned meat was returned to the stew, or with the other root vegetables.

The forgotten hero

Turnips were a root vegetable staple in colonial times. they stored well without refrigeration (like other root vegetables they could be stored in sand boxes) and an important source of Vitamin C. Although still available in grocers shops, seems to have dropped away from our general ingredient list these days, except perhaps for winter soup packs. Compared with carrots, which have become a very cheap ingredient (currently less than $2.oo per kilo), turnips, often the ‘swede’ variety, are around the $5.00 per kilo mark, suggesting a less competitive market for growers and retailers.