Calling all cooks! I’ve had mixed success replicating old recipes, some working out better than others. Of late, a Thatched House Pie has proved to be something of a challenge for me, and is my current culinary conundrum. A version of this pie is one of the many recipes in a manuscript of household recipes compiled in the 1830s, now held in our library collection.

![Thatched house pie recipe circa 1832 from Manuscript recipe book : 1832-1837 [personal papers]. Caroline Simpson Library and Research Collection MSS 2011/1](../../app/uploads/sites/2/2015/10/xthatched-roof-page-blog.jpg.pagespeed.ic.X9vk1vLV4T.jpg)

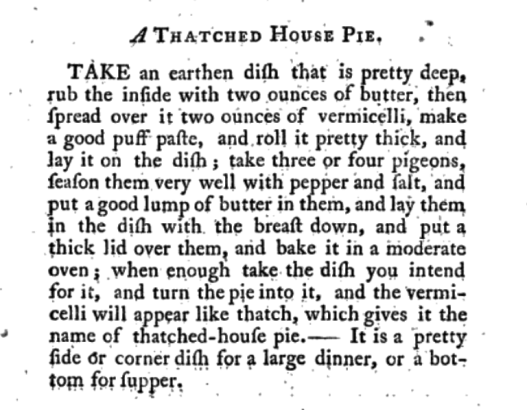

Thatched house pie recipe circa 1832 from Manuscript recipe book : 1832-1837 [personal papers]. Caroline Simpson Library and Research Collection MSS 2011/1

Thatched House Pie Lady Jane James

Take an Earthen dish that is deep rub the inside with 2 oz

of butter then spread over it 2oz of vermicelli make a good

puff paste & roll it thick & lay it in the pie dish take 3 or 4

pigeons season them very well with pepper & salt & put a lump

of butter in them & lay them in the dish the breast down

Put a thick lid over them & bake them in a moderate oven

when enough, take the dish you intend for it & turn the pye

in it and the vermicelli will appear like thatch any meat

will answer if you have not pigeons.

‘A pretty side or corner dish for a large dinner, or a bottom for supper’

I’d come across this recipe before, in Elizabeth Raffald’s The experienced housekeeper, first published in 1769. Southover Press (UK) has published a facsimile edition and various editions are accessible online. The manuscript recipe is almost word-for-word Raffald’s recipe (below), but omits her closing line “It is a pretty side or corner dish for a large dinner, or a bottom for supper”. It’s a great line, a reminder that dishes were never chosen in isolation but selected to be part of an ordered arrangement and sequence as ‘the Curator’ has explored in the past. This manuscript version does add that any meat can be used instead of pigeons – a detail I was pleased to see, pigeons not being easy to come by, or affordable, for the ordinary 2016 cook. Rather than the filling being important to me however, it was the presentation of the dish that most intrigued me; but as yet, I’ve not been able to create a ‘pretty dish’ that resembles a thatched house!

A thatched house pie. Elizabeth Raffald. The experienced housekeeper. 1786 p150. source: archive.com

Decyphering a recipe

These days our recipes are far more detailed and prescriptive, many of them being quite specific about oven temperatures, cooking times, the size of the dish to cook in etc. But when tackling a much older recipe such as this there are several points that remain a puzzle –

What sized dish? What shape? – rectangular presumably, house shape? (I settled on an old-fashioned enamel deep-sided pie dish which I think is ok; (‘The Curator’ mischievously suggests I could have dived in the deep end with a raised pie mould)

How much puff pastry? How thick? Would frozen sheets suffice, folded in two or three layers perhaps?

What type of vermicelli? spagettini # 3? Broken up or left whole? or perhaps the small shredded style sometimes seen in Italian grocers, which are used for vermicelli puddings? Do you cook it first or use it raw, hoping it cooks in the process?

And how to arrange the vermicelli so that it looks like ‘thatch’? Should the ‘thatch’ come down the sides of the dish – should I use a loaf pan? Is the vermicelli thatch meant to be edible or there simply for adornment?

And while I was relieved to find in the manuscript version that I could use a substitute for pigeons, how big would the birds have been and would they have been deboned?

Trial and error

A failed attempt. Photo © Jacqui Newling

To date I’ve not found any illustrations of the finished pie, but presumably the dish was well enough known for the 18th-century reader to understand all these things without needing instructions; the modern cook is left guessing! Needless to say I’ve had several disasters and have not been able to produce a pie that I’m satisfied with. My first attempt was an abject disaster and was fed straight to the dog – I used cooked spagettini (no. 3) which I’d broken into pieces but it looked a flabby mess and nothing at all like thatch.

I felt a bit more confident using shredded ‘dessert’ vermicelli. I didn’t precook it however, as it is so thin, thinking it might soften in the cooking. It did not, and was inedible – back to the drawing board on that issue. Luckily I didn’t use the full 2 ounces (60g) as it would have filled the pie dish, and while it was a bit light-on, encouragingly it did look a little more thatch-like. For the filling I used chicken thigh fillets, with sliced leeks and herbs to add flavour, but the chicken pieces shrank as they cooked and my ‘roof’ collapsed once the pie was turned out. Perhaps I should have used a smaller dish or used more chicken pieces, packing them in more tightly. Or maybe my pastry hadn’t been thick enough to support itself.

Another try © Jacqui Newling for Sydney Living Museums

For my latest attempt I cooked the shredded vermicelli, which I could have been a bit more generous with. I cheated completely on the filling, using an egg and bacon pie filling in the hope that the pie would hold its shape, which it did. Despite the vermicelli being pre-cooked, it ‘fried’ in the butter and still became so hard it would break a tooth and so, in my view, was inedible.

I’ve come to the conclusion that the thatch roof may simply be for affect, and the crust not intended for consumption. This isn’t at all unusual, as many pies in past times did not have edible crusts but were instead, vessels for their tasty insides, broken open and enjoyed. Think of chicken or fish cooked in a salted pastry crust as a parallel: the pastry is there to create a sealed chamber for cooking, then broken open and discarded.

A pretty dish?

Is it a ‘pretty dish’? I think not, but perhaps adorned with broccoli florets around the outside to replicate a garden, it might just pass muster as a thatch house – at a stretch. Perhaps you can make a better go of it?

Lost charm

Thatch itself, as a roofing material, has endured and has considerable nostalgic appeal, but its culinary namesake has become a relic of the past and has quite lost its charm. In my mind the Thatch House pie is the predecessor of the now-classic ‘cottage pie’, and shows what a boon the versatile potato became in the late 18th and 19th centuries. Newer versions of ‘thatched roof’ pies have a mashed potato topping, with the thatch affect created by scratching the fluffy surface with the tines of a fork, before brushing with melted butter and browning in the oven. With the exception of birthday cakes and children’s party dishes (and, as the Curator adds, episodes of Heston Blumenthal or the dinner scene from ‘Close Encounters of the Third Kind’) we are less likely to want to sculpt our food into whimsical shapes for the table, and the much simplified, less-embellished cottage pie has become a comfort dish rather than a ‘pretty’ one for the corner position on an upper class table.

Detective work

We are still researching the provenance of the manuscript and how it made its way from England to Australia. Lady Jane James is one of many ‘contributing authors’ or sources of the recipes in the book, and overwhelmingly the most prevalent. But who was she, and what was the relationship between her and the writer of the manuscript? Megan Martin, Head of Collections here at Sydney Living Museums, has been investigating some of the names cited in the book as sources. It appears from Megan’s research that Lady Jane James (c1757-1825) was the youngest daughter of Charles Pratt, 1st Earl Camden (1713-1794) and his wife Elizabeth (nee Jeffreys, 1725-1779). In April 1780 Jane married Walter James James, Baronet, of Langley Hall, Berkshire. Her brother, who succeeded as the Marquess Camden, was quite significant for Australian history, being instrumental in John Macarthur receiving the land grant he later called ‘Camden’.

Lady Jane James died in September 1825, and several other contributors that Megan has managed to trace were long dead by 1832 when most of the entries in the manuscript are dated. Identifying Lady James helps make sense of the ‘vintage’ of many of the recipes in the book however, which, especially with their decidedly short-handed recipe-writing methods, seem somewhat out-dated for the 1830s, ‘thatched house pie’ being one of them.

Megan is now of the the view that the compiler (who we think may be Ann Weaver, nee Bradbury, who emigrated to New South Wales in 1853) was either making a clean copy of an earlier manuscript or compiling something from a collection of loose pages. Its a riddle that may never be resolved.

Sources and further reading:

Elizabeth Raffald The experienced housekeeper, 1786 (first published 1769).