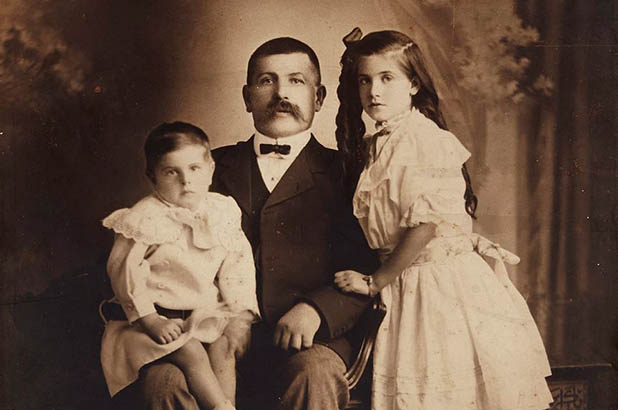

Dolly’s ‘Cooking homework book’ is 101 years old. Jenny (known as Dolly) Youngein (pictured, right) lived in Susannah Place at 64 Gloucester Street, where her parents ran the corner shop from 1904. Dolly was 12 years old when she created the book. It is still in her family’s possession and is a treasured memento of her childhood.

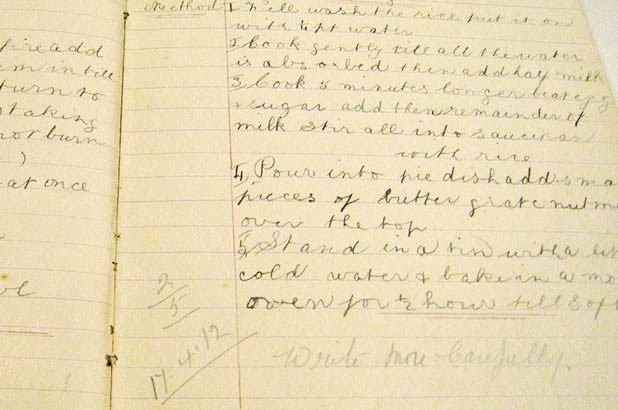

In 1912 Dolly was a pupil at the local Fort Street Superior Public School. Her carefully noted handwritten recipes were a product of school cookery classes. Despite her efforts at recording her recipes, Dolly sometimes received poor marks and her work suffered several red-pencil corrections for her handwriting skills, with comments such as ‘write more neatly’ and ‘rule neat lines’ written in the margin by her teacher.

Cooking credentials

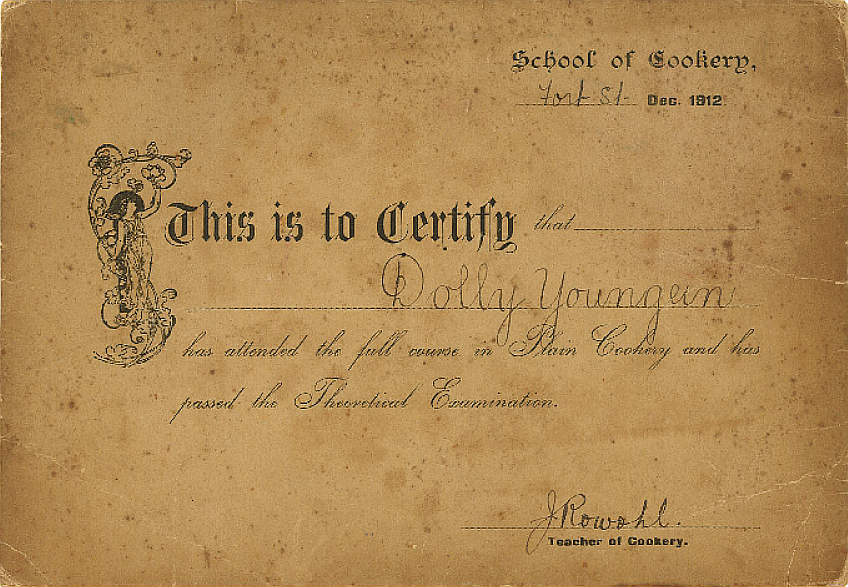

Despite her teacher’s criticisms, Dolly received a printed certificate from the ‘School of Cookery’ at the end of the year, certifying that:

‘Dolly Youngein has attended the full course in Plain Cookery and has passed the Theoretical Examination’.

Dolly Youngein Fort Street School cookery certificate. 1912. Courtesy John Brown. © Sydney Living Museums

Formalised cookery education programs had become increasingly influential since the 1880s. English-trained cookery teachers made their way to Australia and became influential voices with locally published cookbooks. Margaret Pearson, Australian Cookery for the People (c1890), Harriet Wicken, whose recipes appear in Phillip’s Muskett’s Art of Living In Australia (1893) and Margaret A. Wylie, The Golden Wattle Cookery Book (1926), highlighted their London ‘diplome‘ training credentials and/or their association with institutional cooking programs to add authority to their works.

Necessary skills for novices

While there’s no evidence of Dolly cooking the recipes she recorded, the book tells us what type of dishes and techniques were deemed necessary for a novice cook, albeit of a young age, in the early 1900s.

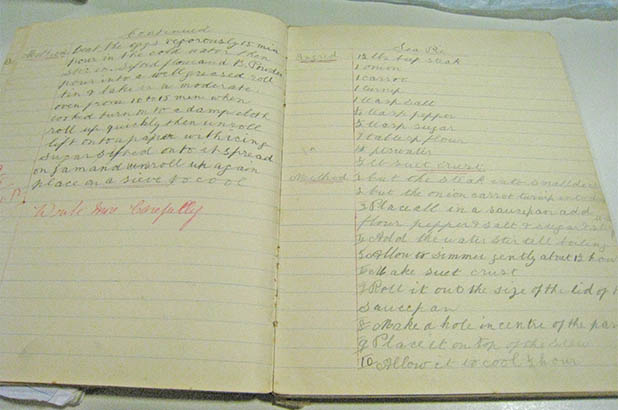

Savoury dishes include Mutton Broth, Baked Vegetables, Steak & Kidney Pudding and Sea Pie; dessert dishes include Blanc Mange (in this case, sweetened milk thickened with cornflour), Boiled Custard (the addition of an egg is all that distinguishes it from the blancmange), Rice Pudding, Jam Roly, and a curious sounding Sweet White Sauce – an alternative to custard it would seem. Both the Steak and Kidney Pudding and the Jam Roly are boiled puddings, made with suet pastry, and stand testament to a tradition of stove-top cookery over oven baking. Similarly, the Sea Pie is more of a pudding or ‘pot-pie’, made in a saucepan on the stove.

An ocean-going pie

Sea Pie is a curious dish that pops up from time to time in old cookery books. Contrary to the name, they are invariably meat-based, in the same family as a shepherd’s or cottage pie, made with a potato or suet-crust pastry topping. The idea was that they could be made while traversing the globe on ships in an oven, if one was available, or in a saucepan on a stove. Dolly’s recipe is not dissimilar to the one in Girlie Andersen’s Golden Wattle cookbook (a product of an institutional cookery education program).

First you make a simple beef stew in a saucepan, flavoured with onions and root vegetables and thickened with flour. The Golden Wattle version added a sheep’s kidney. Once cooked, suet (short-crust) pastry is rolled out to the same size as the saucepan, using the lid as a guide, and laid over the stew. A small hole was made in the centre to let steam escape and the ‘pie’ would then cook on the stove for another half hour or so before serving.

I can only imagine that the pastry top would look somewhat unappetising to a modern eye, as it would steam rather than bake and therefore not colour, and would be a soft rather than crisp texture. In this sense it seems more like a pudding than a pie, but this in itself demonstrates how our expectations and understanding of things, and therefore our tastes, alter over time. Perhaps it could be popped under a salamander or griller to make it more appealing for a modern aesthetic. If you can master a basic short pastry, this could be a handy dish for camping holidays.