One of the best documentary sources for kitchens and dining rooms in the colonial period isn’t actually family archives – but newspaper and auction advertisements. Individuals leaving the colony after a few years – or facing ‘pecuniary embarrassment’ – would typically sell up, so lists of household effects are fairly common. Larger sales warranted their own catalogues, which could be broken down room by room; for a curator these are a goldmine of information as to furnishings and paraphernalia, artworks and even what books were in personal libraries.

To be sold by Mr Bodenham

For this series of posts on understanding the batterie de cuisine, however, it’s the contents of kitchens and dining rooms that grab our attention. In 1828 John Oxley, the prominent explorer and surveyor, died aged only 42, and the contents of his Sydney home – at the corner of King and Macquarie streets, facing St James’ church to the south and the Hyde Park Barrack to the east and now the location of the Supreme Court tower – were put up for sale by the prominent auctioneer Thomas Bodenham. The items were divided up by the 15 rooms (excluding stables and outbuildings), with the kitchen contents listed as:

7 iron Saucepans in [various] sizes and 1 Stew Pan

1 Frying Pan, 1 Grid Iron,

2 large Fish Kettles and strainers and 1 copper coal skuttle

1 Bakers Trough [ie a dough bin]

1 [meat] safe, with shelves and stand

2 oyster Patties, 2 funnels, 1 sieve, 1 spice box, 1 cheese toaster [salamander], 1 cullender, 1 fish slice, and 12 ladles, 1 spice and coffee mill

1 cast iron Oven and fittings

2 Cranes and Hooks with bars for grate

Also for sale were:

1 dresser and stand,

4 chairs

1 set of opaque china, comprising 2 vegetable dishes, sallad ditto, a soup and 1 turreen, 12 soup and 24 large plates, 6 water plates, 5 dishes, 1 fish strainer

1 dresser and stand; 5 paper [ie papier mache] tea trays and waiters [small hand trays]

You can see why these lists are so valuable to curators, especially when setting out to recreate a historic interior. This list gives a good snapshot of the contents of a well-to-do kitchen in Sydney in the 1820s. Its fit-out would be instantly comparable to that at Elizabeth Farm. The ‘2 cranes’ tell us that the Oxley’s kitchen had an open range, not yet a fully closed range, with the iron saucepans suspended over the fire on pivoting metal brackets.

The Oxley’s saucepans were of black iron, not the familiar (and iconic) coppered tin designed to sit on top of a stove. Although an oven is mentioned it is a portable one, a Dutch or ‘camp’ oven frequently seen in advertisements. This was basically a large iron pot with a lid, or box with a door, designed to be slotted into the open hearth and covered in coals. Oddly there’s no mention of a spit or roasting jack – which would be a standard fixture.

Of course you’ll have spotted the two ‘fish kettles’ – while the ‘fish strainer’ was either the insert that lifted the fish out of the kettle, or a pierced ceramic drainer insert that sat on a larger platter.

Jump forward to the 1840s and we have a goldmine of information, as the economic crash that hit New South Wales in 1840 led to a succession of partial and full house auctions over the following years. You can generally tell the difference quickly: full auctions contains all sorts of odds and ends, while partial sales tend not to include these random jars, bottles and lids – and interestingly knives rarely appear.

‘At the residence of Mr Manning’

In 1842 John Edye Manning, registrar of the Supreme Court of New South Wales, went bung was declared insolvent and his household effects at Ultimo House, just west of Sydney and which he had been renting, were put to auction. The kitchen contents were sold in one large lot, and give a good idea of what was found in a – well lets call it a ‘previously’ prosperous – colonial household. In amongst the candlesticks, spoons, nutmeg graters, hair sieves and coffee pots, were:

1 8-gallon iron kettle, 1 3-gallon ditto, 1 5-gallon pot and cover, 1 fish kettle, 2 copper stew pans and covers [i.e. the lids], 4 iron ditto of sizes, 4 large saucepans, 4 smaller ditto, 2 frying pans, 1 gridiron…

Its a fairly standard number of pots and pans, and not many more than were in the Oxley’s house. When you look at similar auctions there might be 1 or 2 more stewpans, maybe another frying pan, and often another fish kettle, but we see here the fairly standard complement for a middle-class house. This time there were also “two bottle jacks” for roasting.

Across the harbour three years later, the contents of William Gibbes’ Beulah, at Kirribilli, contained “6 saucepans, 3 frying pans, 1 gridiron, 1 Dutch oven” and a dripping pan for roasting. The same year, Elizabeth Bay House formally passed to William Sharp Macleay, who had been bankrolling his father for many years. The deed lists the kitchen content which, while extensive, still only contained:

4 copper stewpans and covers; 2 iron stewpans and covers; 1 copper stock pot; 1 fish kettle; 1 small fishkettle; 1 grid iron; 2 frying pans… 2 salamanders…

And not a suspended jack, but “10 spits for roasting”: these would have been positioned horizontally in front of the flames. Ironically, the cash-strapped Macleays of Elizabeth Bay House were not known for their entertaining, so their batterie de cuisine wasn’t exactly getting a workout. Again, the contemporary kitchens at Elizabeth Farm and Vaucluse House would not be markedly different.

‘By Appointment to Her Majesty’

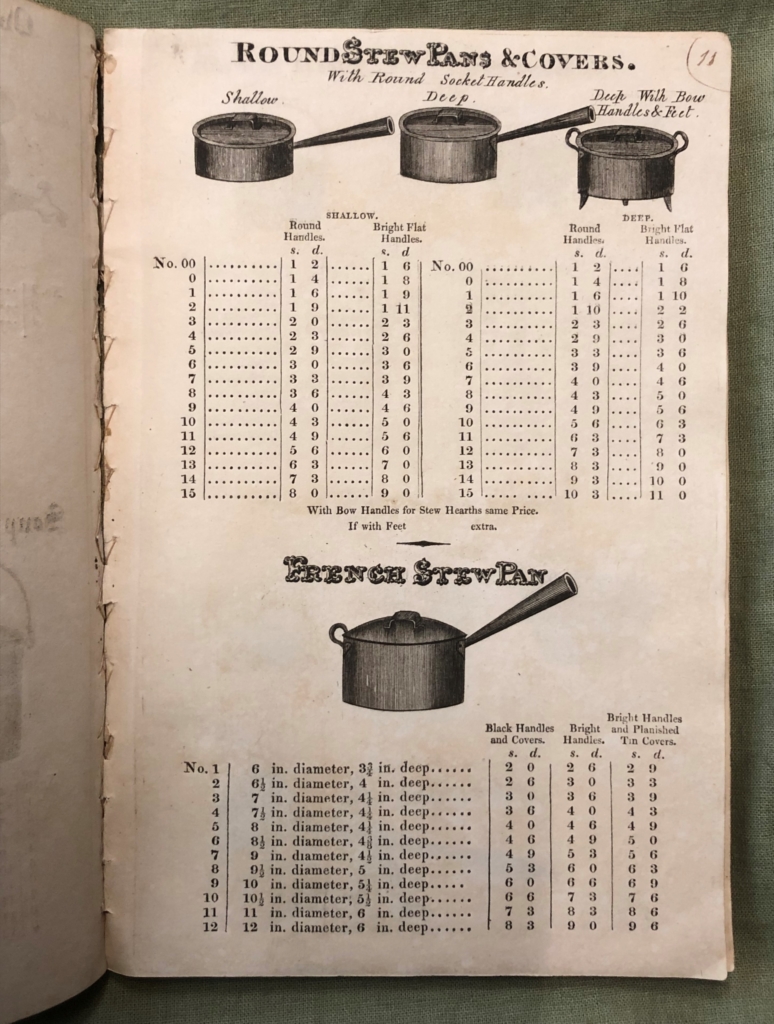

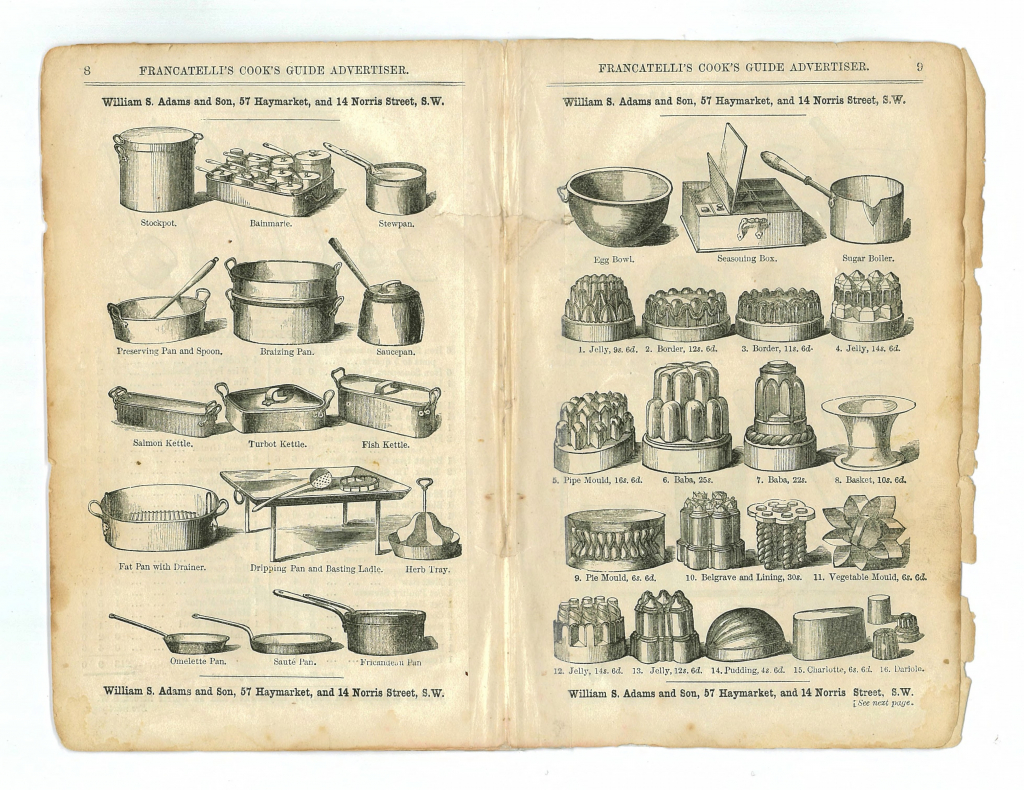

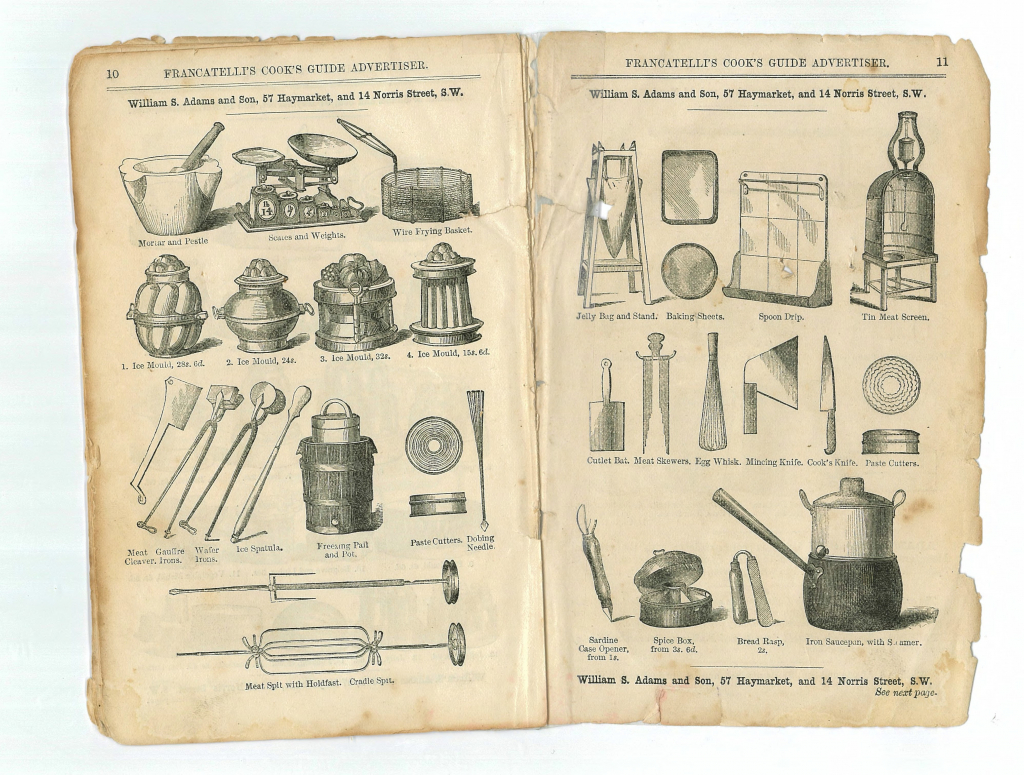

The iconic kitchen of the (later) 19th century so beloved by movie and tv stylists, is of course one full of gleaming copper pots and jelly molds, all increasingly specialised; but where did the fashionable homeowner with an eye to entertaining fit out their kitchen? In the collection at the Caroline Simpson Library are two British trade catalogues that illustrate what was available. The first, for H Barns & Sons, General Iron Founders of Birmingham, dated 1822, contains an extensive range of size and material options, illustrated by someone with a less than perfect grasp on perspective:

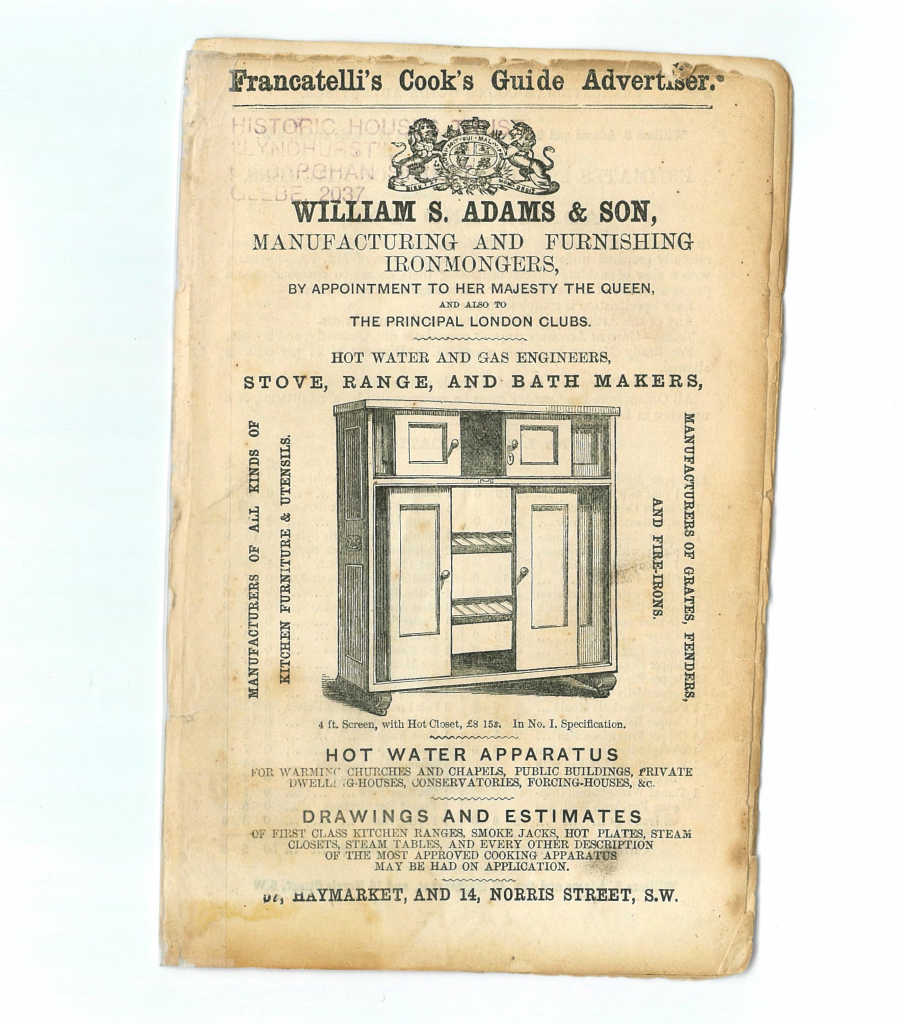

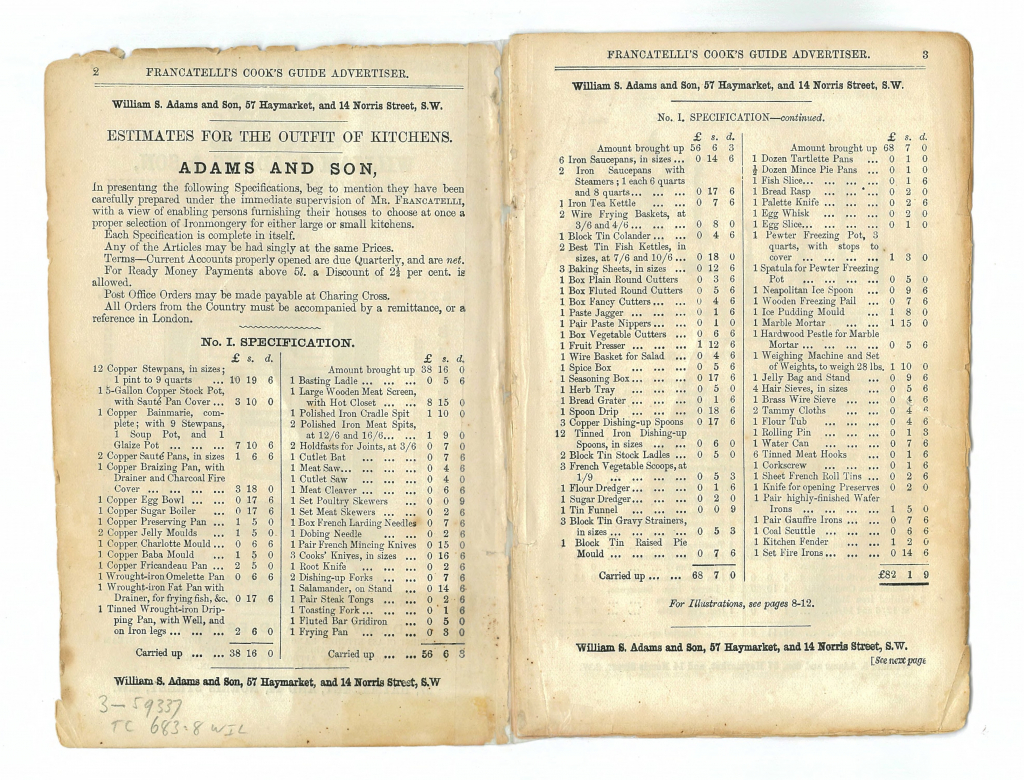

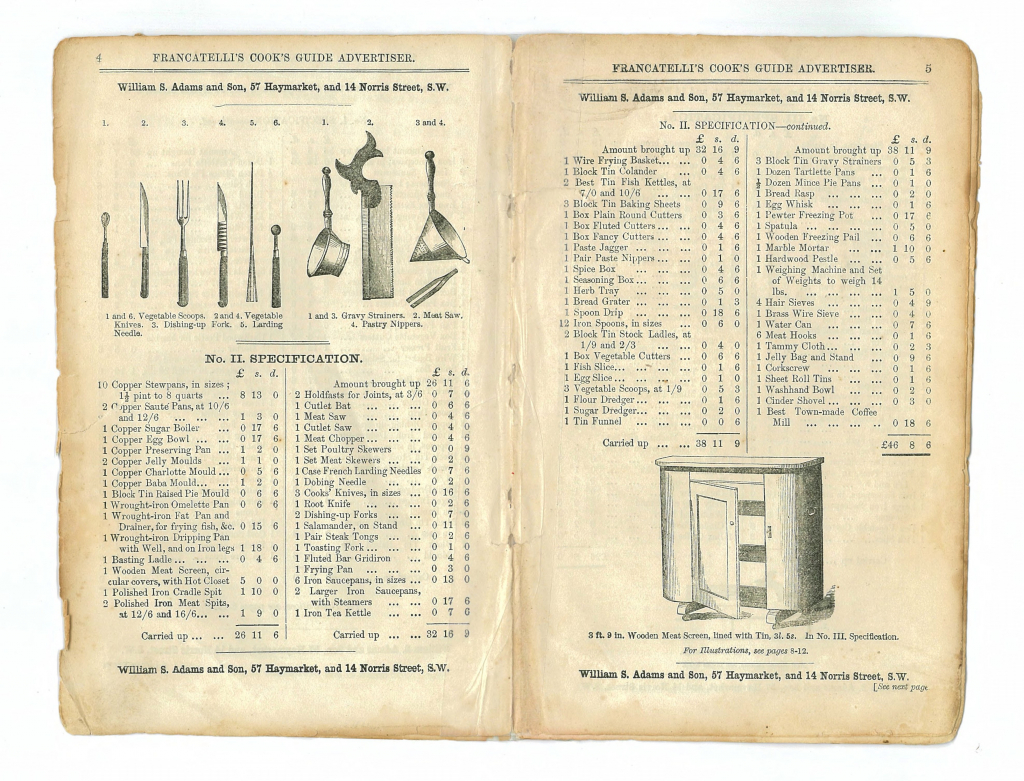

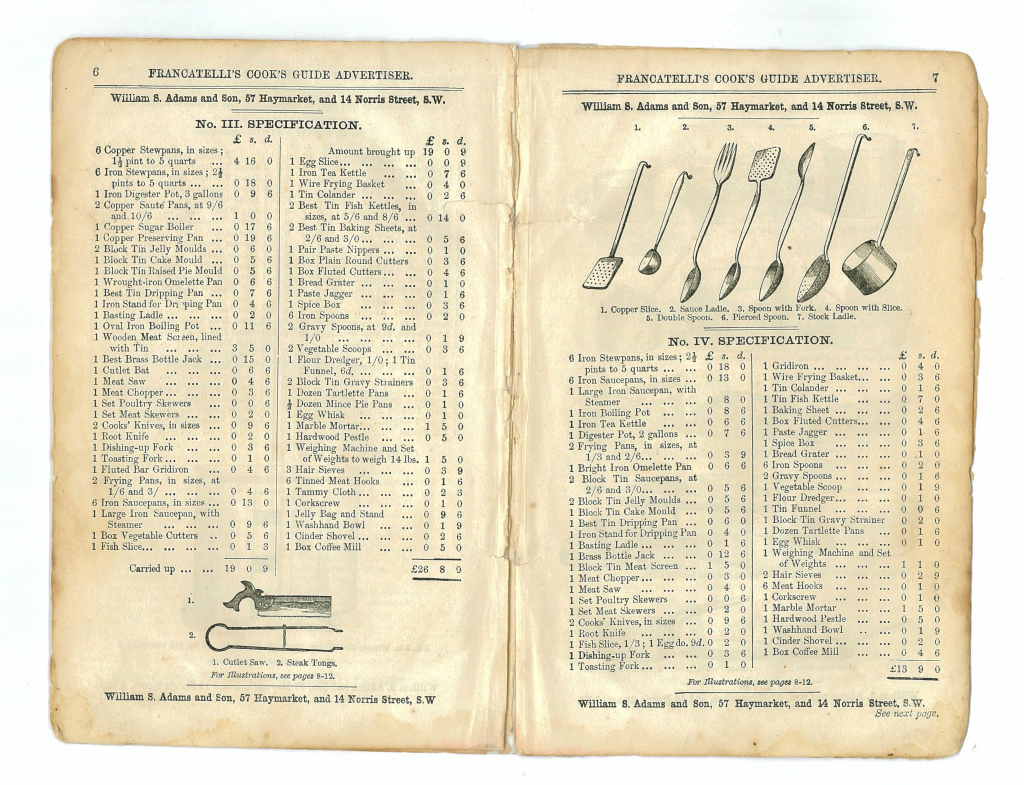

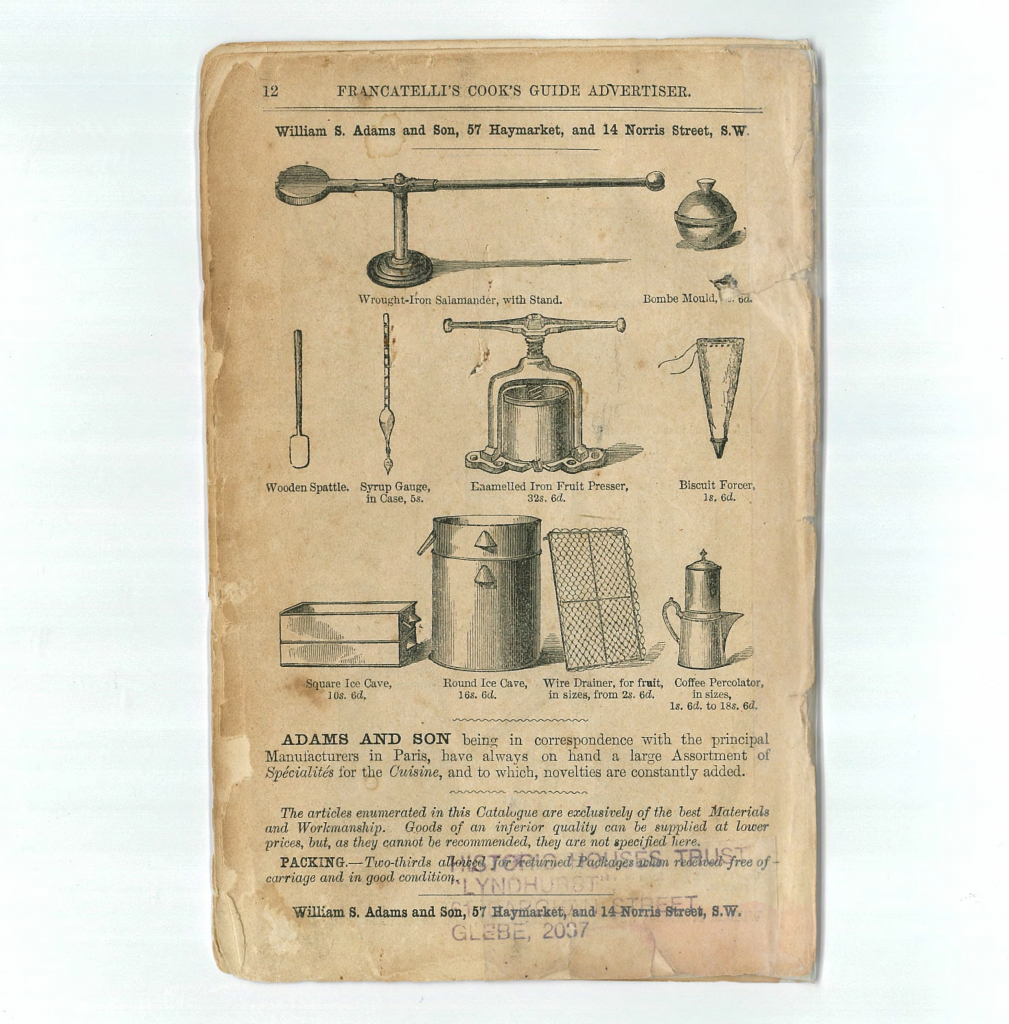

The second is the ca1860 ‘Francatelli’s cook’s guide advertiser’, produced by William S. Adams & Son – “manufacturing and furnishing ironmongers, by appointment to Her Majesty the Queen, and also to the principal London clubs”. This featured entire ‘kitchen kits’ ready to go:

4 specifications, carefully prepared under the immediate supervision of Mr Francatelli, with a view of enabling persons furnishing their houses to choose at once a proper selection of ironmongery for either small or large kitchens.

Charles Elmé Francatelli (1805–1876) was, like Alexis Soyer, one of the great celebrity chefs of 19th century London. One time cook to Queen Victoria, later to the Prince and Princess of Wales, and head chef to a selection of the great Clubs of London, he was the Jamie Oliver or Nigella Lawson of his day – and like them he used his name to promote kitchen merchandise and wrote a series of cookery books. This catalogue provided 4 ready-to-go batterie de cuisines, from a very aspirational set at £82, to sets at £46, £26 and £13.

‘Set 3’ contained 6 stewpans, 6 saucepans, 2 frying pans, oval iron boiling pot, a gridiron, fish kettle, and 2 jelly molds, and sounds very much like the set we’d expect at Elizabeth Farm. In colonial Sydney, with its (let face it, a chronic) shortage of trained (let alone experienced) cooks, there was simply no need for a more complex arrangement.

So in conclusion, after a lot of lists the contents of a middle class kitchen in Sydney in the 1820s through the ’40s were pretty standard, and even for decades afterwards there is little real change. If I were to fit out a ‘standard batterie de cuisine’ with its pots and pans, it would probably contain:

4 copper stewpans and covers; a ‘black iron’ stewpan; 3 large and 3 small copper saucepans; 1 stock pot; 1 fish kettle; 1 tea kettle; 3 frying pans; 1 grid iron; a suspended roasting jack; and a salamander…

Now I’m off to Bodenham’s to pick up a bargain. Cheers!