During one of the floor talks for Eat Your History: a Shared Table a conversation started at the curio wall regarding a piece of kitchenalia you never see anymore, the bottle jack, and a very old question indeed: do you bake, or do you roast? As a quick test, ask yourself and the people around you: do you sit down to a roast dinner, or a baked dinner? If you roast a chicken, then why do you bake potatoes? Surely they’re all cooked in the same oven? It’s actually a very good example of how language and the way we use words can carry older meanings, often as technology changes or improves. Another great example of changing terminology is whether you sit down to ‘dinner’ or ‘tea’ in the evening, or whether a formal midday meal on Sunday is ‘lunch’ or ‘dinner’.

Some definitions from Johnson’s Dictionary of the English Language (1st edition, 1755) distinguish baking and roasting:

Bake: to heat anything in a close [i.e. ‘enclosed’] place; generally in an oven.

Roast: to dress meat by turning it round before the fire; to impart dry heat to flesh; to dress at the fire without water.

Spit: a long prong on which meat is driven to be turned before the fire.

Jack: An engine which turns the spit.

The important distinction are the words ‘dry heat’ and ‘without water’. Johnson is distinguishing here between two fundamental techniques of cooking: by placing food in water which is then heated or, as in the case of baking and roasting, by radiant heat. In modern baking, barring the eccentricities that all ovens have, the heat ideally comes from all directions. To ensure airflow around meats and prevent stewing, racks are often placed in the pan or dish to elevate the meat above the collected juices or fats (which are used to baste the meat and later as the base for a rich gravy). To Isabella Beeton the lack of ventilation in most enclosed ovens gave meats a ‘peculiar taste’. In roasting however the heat is primarily coming from one direction, either from beneath or to one side.

In the colonial kitchen

If you were cooking in the colony in the late 18th and indeed well into the 19th century, joints of meat were either boiled, or cooked in front of an open fire either on horizontal spits or suspended vertically. This second technique is what is by definition called roasting. Breads, vegetables and pies meanwhile were baked in an enclosed oven. True roasting in its historical sense is distinguished now by the name ‘spit-roasting’ – it’s the technique you see in ‘charcoal chicken’ shops.

Kitchen and fireplace at Berrima, New South Wales, Hardy Wilson, c1920. Hardy Wilson Collection, National Library of Australia © Estate of the artist

‘Open ranges’, a feature of early colonial kitchens,were basically broad openings, where pots and ‘stirrup’ griddles were suspended by brackets, chains or hooks over the open flames. Pivoting brackets were also used, to swing a pot in or out. In this mode, when cooking a joint a horizontal spit was used. These varied greatly in their sophistication, from simple hand-turned spits, to quite complex apparatus turned by fans located in the chimney and rotated by rising smoke. (Those designed by Antoine Careme for the Royal Pavilion at Brighton are a tour de force). Mrs Beeton called these ‘smoke jacks’. She notes:

IF A SPIT is used to support the meat before the fire, it should be kept quite bright. Sand and water ought to be used to scour it with, for brickdust and oil may give a disagreeable taste to the meat. When well scoured, it must be wiped quite dry with a clean cloth; and, in spitting the meat, the prime parts should be left untouched, so as to avoid any great escape of its juices.

In large scale 18th and 19th century festivities, bullocks, pigs or sheep roasted entire on a spit were a feature. The bullock roasted at Vaucluse House to ‘farewell’ Governor Darling is one that we’ve featured before.

Later cast iron ranges, with dedicated spaces for an oven and water heater to the sides, and often retrofitted into an earlier opening, had the characteristic narrower contained space for the coal fire so a suspended system was more practical. The stacked coal in the fire box created a wall of highly radiant heat, ideal for roasting. This is the style of stove seen in the kitchens at Elizabeth Farm [below] and Vaucluse House today. In Hardy Wilson’s rather nice c1920 view of a cottage kitchen [above], you can see an early and quite basic box-like enclosed oven set into an earlier, wider opening, with a brick hob constructed to either side. In this case a fire could be lit beneath AND on top of the oven, and pots could be hung from the two curved – and most likely pivoting – brackets. Its a hybrid between the earlier and incoming styles.

The first of this ‘improved’ type of cast iron stove was patented in 1780, by Thomas Robinson in London. The greater developments however took place after 1802, when Count Benjamin Rumford (the philanthropic inventor) published his essay “The construction of Kitchen Fire-Places and Kitchen Utensils”. Rumford’s aims were to design according to scientific principles, to both dramatically reduce excessive fuel consumption and improve actual cooking. While his actual inventions were soon superseded, the concepts and principles spawned a kitchen revolution.

“Spare the basting and spoil the meat”

Along with a discussion of the chemical changes that occur during cooking (this was after all the heyday of the Industrial Revolution), Beeton gives this definition of roasting:

OF THE VARIOUS METHODS OF PREPARING MEAT, ROASTING is that which most effectually preserves its nutritive qualities. Meat is roasted by being exposed to the direct influence of the fire. This is done by placing the meat before an open grate, and keeping it in motion to prevent the scorching on any particular part. When meat is properly roasted, the outer layer of its albumen is coagulated, and thus presents a barrier to the exit of the juice. In roasting meat, the heat must be strongest at first, and it should then be much reduced. To have a good juicy roast, therefore, the fire must be red and vigorous at the very commencement of the operation. In the most careful roasting, some of the juice is squeezed out of the meat: this evaporates on the surface of the meat, and gives it a dark brown colour, a rich lustre, and a strong aromatic taste. Besides these effects on the albumen and the expelled juice, roasting converts the cellular tissue of the meat into gelatine, and melts the fat out of the fat-cells.

Bottle jack used to turn a roasting joint of meat before a kitchen fire. Photo © Stuart Miller for Sydney Living Museums

Which brings us back to the bottle jack that was in the curio wall. To be used, the bottle jack is suspended above the fire, say from the chimney-piece, with the joint then hung below it from the in-built hook. The jack is wound up, and then slowly turns, rotating the meat (though I did see one demonstrated once whose spring had gone, and as a result it spun like the Rotor at Luna Park). Think of it as being like the meat cooking as it turns in a kebab shop and it makes perfect sense. Beeton writes:

THE BOTTLE-JACK, …. is now commonly used in many kitchens. This consists of a spring inclosed in a brass cylinder, and requires winding up before it is used, and sometimes, also, during the operation of roasting. The joint is fixed to an iron hook, which is suspended by a chain connected with a wheel, and which, in its turn, is connected with the bottle-jack. Beneath it stands the dripping-pan, which we have also engraved, together with the basting-ladle, the use of which latter should not be spared; as there can be no good roast without good basting. “Spare the rod, and spoil the child,” might easily be paraphrased into “Spare the basting, and spoil the meat.”

In this illustration you can see a cook spooning up the hot dripping from a tray where it falls, and onto the suspended joint to keep it moist as it turns. Note the high stack of burning coals in the range Reflectors could also be used as well, placed on the side of the roast away from the fire to both reflect the heat and concentrate it, speeding up the cooking process:

View of an ‘Australian Kitchen’ (detail) showing a bottle jack in use, Mrs Isabella Beeton, Mrs Beeton’s book of household management, London, 1880-85. Sydney Living Museums R89/80

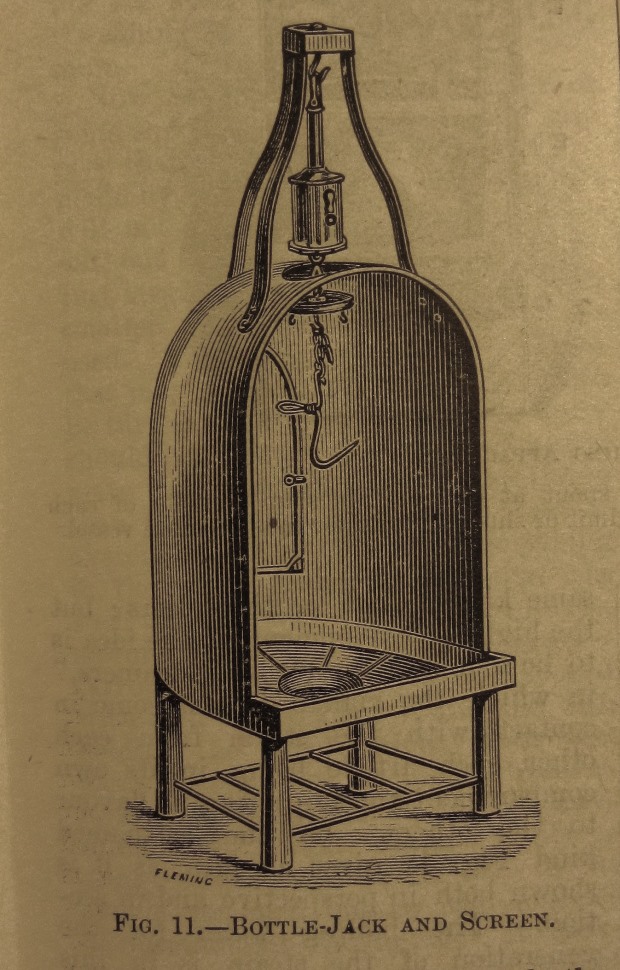

In my 1909 Cassell’s Household Cookery is this illustration of a bottle jack ready for use with a portable screen to concentrate the heat and shield the cook. There’s a door in the back so the cooking progress can be checked without moving the apparatus. The text notes a DIY variation: “Those who do not wish to go to the expense of a bottle jack may find an economic substitute in the… chimney screw-jack, which may be hastened upon any mantleshelf when wanted… It requires a little more attention than a bottle jack, but if a key be hung upon the hook with seven thicknesses of worsted wound round it, one end of which is fastened to the meat- hook, the twisting and untwisting of the worsted cord will cause a rotary motion like that produced by the most expensive bottle-jack.”

Illustration of a bottle jack and surrounding screen from Cassell’s Household Cookery, Melbourne, Casell & Co., 1909

So to answer the question: Do you bake, or do you roast? The answer is simple: you do both. Words change in time, but what is important is that language carries meanings and encoded history – whether we recognize it or not. While we use modern ovens for both ‘roasting’ and ‘baking’, the semantic convention is that we ‘bake’ vegetables, pies, pastries and breads, and we ‘roast’ meats. It may use the same mechanism, but hearkens back to much older methods and different technology. One term that is unlikely to change for some time is ‘barbecue’! I leave the final word for today’s post to Henry Fielding:

Our fathers of old were robust, stout, and strong,

And kept open house, with good cheer all day long,

Which made their plump tenants rejoice in this song–

Oh! The Roast Beef of old England, And old English Roast Beef!Henry Fielding, The Grub Street Opera. 1731

Dig deeper

Pamela Sambrook and Peter Brears’ The Country House kitchen, 1650-1900: skills and equipment for food provisioning, London, Sutton Publishing in association with the [UK] National Trust, 1997, is an excellent read, and discusses Rumford’s inventions pp106-9.

A personal favourite is Mark Girouard’s groundbreaking Life in the English country house : a social and architectural history, Harmondsworth, Middlesex: Penguin, 1980. This book changed the way I and many others understand the historic house.