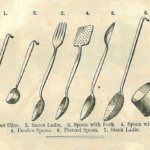

A phrase you’ll often hear in a historic kitchen is batterie de cuisine. Though the term today is not often heard outside of professional kitchens and house museums, every household has one. It simply refers to the moveable collection of pots, pans and equipment used in a kitchen, though not the stove or large appliances.

With the growing interest in historic life ‘below stairs’, boosted by television period dramas featuring accurately recreated kitchens (you know which one I mean), house museums now take great pride in their kitchens and associated spaces. If you’ve ever been to Petworth, a historic house in England, you’ll have seen the famous kitchen with its vast collection of gleaming copper pots.

The Vaucluse House batterie de cuisine

Vaucluse House has an extensive batterie de cuisine of 137 pots, pans and jelly moulds. Though not provenanced to the Wentworth family, it represents a typical collection for a large colonial Victorian household. They are made of copper – an excellent and even heat conductor – lined with tin – which stopped any food being poisoned by excessive contact with the copper. Several pieces show signs of repair by a tinker, an indicator of their value and the expense of replacing them.

At Vaucluse House the pots were cleaned in the scullery at a low slops sink where the scullery maid would kneel; the sink then emptied towards the nearby creek. The heavy scouring on the Vaucluse pots suggests that at some stage salt, sand or a similar coarse abrasive was used to clean them. To bring up the gleaming colour, lemon juice was used as a polish – definitely not kind on the hands while you do the dishes.

The much-quoted sage of the Victorian kitchen, Isabella Beeton, gave the following advice as to the care and use of kitchen pots and pans:

As not only health but life may be said to depend on the cleanliness of culinary utensils, great attention must be paid to their condition generally, but more especially to that of the saucepans, stewpans, and boilers… Soup-pots and kettles should be washed immediately after being used, and dried before the fire, and they should be kept in a dry place, in order that they may escape the deteriorating influence of rust, and, thereby, be destroyed. Copper utensils should never be used in the kitchen unless tinned, and the utmost care should be taken, not to let the tin be rubbed off. If by chance this should occur, have it replaced before the vessel is again brought into use. Neither soup nor gravy should, at any time, be suffered to remain in them longer than is absolutely necessary, as any fat or acid that is in them, may affect the metal, so as to impregnate with poison what is intended to be eaten…

Mrs [Isabella] Beeton, Book of Household management. Chapter III: ‘arrangement and economy of the kitchen’ 1861.

But how could even a large household possibly use so many pots?

The answer lies in the increasing specialisation of the 19th century kitchen, with inventors of kitchen paraphernalia including Alexis Soyer and Count Rumford, and with the influence of highly trained French chefs who had begun to move to England after the French Revolution. This influence peaked during the reign of George IV, who attracted the ‘superstar chef’ Antonin Carême to his court. Coupled with the invention of the flat topped ‘closed range’ cooking stove on which to place them, soon there were an ever growing range of pots for highly specialised uses: for poaching a specific fish, creating a myriad of complex sauces, for boiling, braising, stewing, frying and fricasseeing.

The list went on – and the washing piled up.