While the Curator rattles the pots and pans, I’m looking at the cooking ‘apparatus’ upon which they were used at various points in time. We’ve recently looked at domestic hearth cookery from the early 1800’s, but today I’m taking us to the First Fleet encampment at Sydney Cove in 1788.

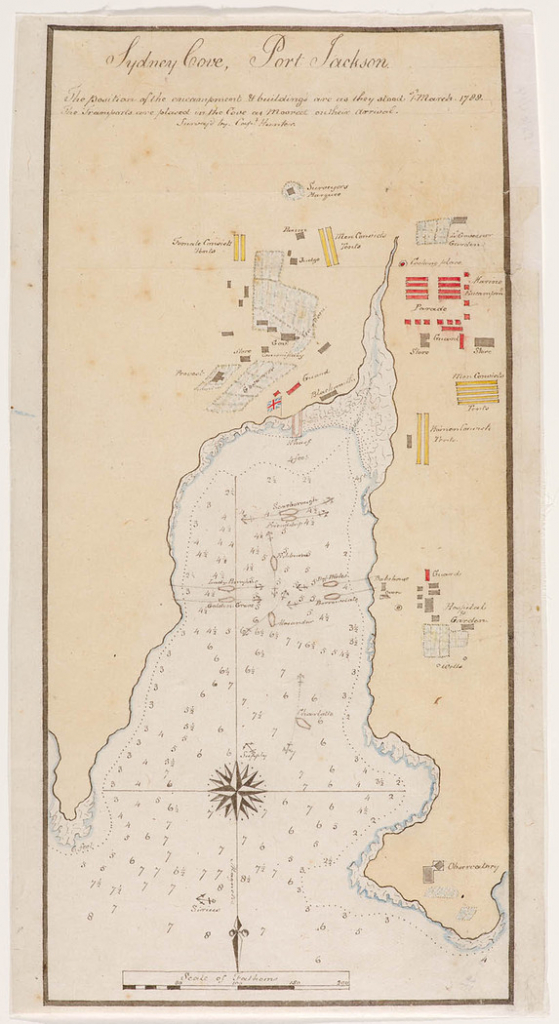

The circular mark to the right of the stem of the stream denotes the cooking place.

A hand-drawn ‘map’ of the embryonic Sydney settlement (shown in part, above and in full at the end of this page) depicts a ‘cooking place’ with a red spot surrounded by dots, looking something like a target or bulls eye. It is conveniently positioned near the head of the stream, just south of the rows of marines’ tents, which are also coloured red on the map. There is a similar ‘bulls eye’ further north, in the vicinity of the hospital, however it is not coloured in or marked as a cooking place (see full map at the end of the page).

Boiling over

The cooking place was a shared, communal facility. Communal coppers and ‘kettles’ were used aboard ships, mounted on a brick structure in which a fire would be lit. In less permanent situations, large iron pots or cauldrons could be suspended over fire from a portable tripod or cross-bar as shown below, so I originally imagined this ‘cooking place’ to be similar, where people could come to boil their rations.

Self education

A visit to our (ex)colonial ‘cousins’ at the American Revolution Museum in Yorktown, Virginia made me rethink my theory. One of the features of this ‘living history’ museum is an outdoor camp that depicts daily life for soldiers of the revolutionary army under George Washington in the early 1780’s. Included in their displays of a tent-village is a ‘field kitchen’ fashioned out of earth, which was typical in British – and anti-British –military camps from the early 1700’s.

Further evidence

Artworks of military camps from the Georgian period show similar formations. A row of ‘cooking places’ can be seen along the boundary wall to the left of a painting by Samuel Hieronymous Grimm from 1780, shown below, with smoke being emitted from some of them.

DIY instructions

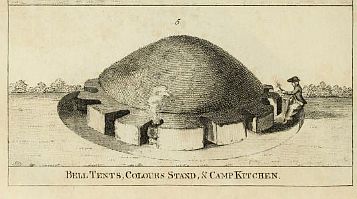

The process for constructing the field kitchen and the benefits of their use are described in A Treatise of Military Discipline, In which is Laid Down and Explained the Duty of the Officer and Soldier, Thro’ the Several Branches of the Service (pp. 244-245) by Humphrey Bland and an updated version with illustration (below) can be found in Military Antiquities respecting a history of the English army, from the conquest to the present time by Francis Grose, 1801 (pp. 37, 39).

Accessed via Archive.org. https://archive.org/details/militaryantiquit02grosuoft/page/n87

The field kitchen at the American Revolution Museum in Yorktown (shown below and at top) is based on Humphrey Bland’s technique, where the fires in the cooking stations are covered, sheltering the flames from rain and more importantly, minimising the risk of fires spreading or sparks flying which might ignite canvas tents or worse, a poorly positioned munitions store of gunpowder!

To build the kitchen, a circular trench is dug into the ground, and the earth removed from the trench is piled on top of the area within circle to form a mound. The edges of the mound are packed down or reinforced with mud to prevent them from caving in. Cavities are dug into the edge of the mound, in which the fires will be located. Small holes are then cut from above, about 30-40 cm from the edge, which will act as cooking points or hobs. Very little fuel is required or wasted, and the natural airflow from the two connected openings helps fan the heat.

Messing about

This type of cooking set-up was highly practical and efficient, especially for an ‘itinerant’ army. It could be dug out of the earth within a day, and once formed, could be operated by a number of cooks at one time, depending how many ‘hobs’ were built into the structure. Ideally there would be as many hobs as ‘mess’ groups in the regiment. Each mess group comprised six men, with each man taking his turn on a roster basis, to prepare a meal for his mess-mates.

To cook on the fire, a pot or ‘billy’ style kettle can be sat on top of the upper opening, over the flame. Standing in the trench, the cook can tend to the pot without having to bend down too far, or can sit on the bench that is formed on the outside of the trench. And as the cooking is done in full view of the soldiers’ supervisors and fellow mess-mates, the opportunity for ‘purloining’ any of the rations for personal benefit is minimised.

Where there’s smoke…

The image above, by Tomkins, 1782, appears to feature similar cooking facilities. It is somewhat curious however, as the mounds are very close together, and show smoke pluming from a central funnel, which is incongruous with the field kitchen described by military handbooks of the time. Was the painter unfamiliar with the way they functioned and interpreted them incorrectly, or is it yet another version of the same principle? That’s a question we will have to leave bubbling away on the stove….

Further reading

For a detailed analysis of earthen camp kitchens, their construction and use see Rees, John U. ‘”As many fireplaces as you have tents …” Earthen Camp Kitchens’ Originally published in Food History News (Fall 1997).