Eagle-eyed reader Ariela asked about an usual item listed in the ‘third drawer down’ – Slacks patent digester! So chop up your turnips and gather those leftover bones – this week we’re in for for some thrifty high pressure cooking.

Slack’s patent digester

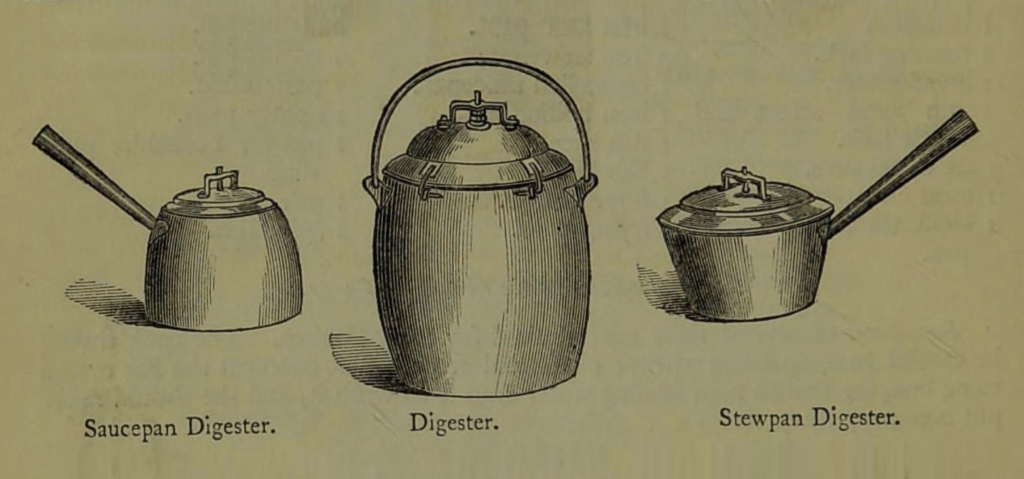

I’ll admit I was secretly hoping someone would ask, and I did receive a few puzzled questions, so I’m rather glad Ariela sent in her question. The ‘Slack’s’ part aside – they were just one of several patent-holders for variations on the concept – a digester is worth a digression before I dive back into pots and pans. Far from some bizarre Victorian invention that does the chewing for you, in essence its a pressure cooker!

The digester is a pot (provided with a pressure gage [sic]), the cover of which can be screwed down, so that the contents can be subjected to both heat and pressure.

Scientific American, January 4th, 1873.

Warne’s Model Cookery – where Slack’s product made its appearance last time – explains the digester. Its a long quote, but neatly covers both the principle and the method of using a digester:

The great importance of the digester, not only to poor families but to the public in general, in producing a large quantity of wholesome and nourishing food, by a much cheaper method than has ever hitherto been obtained, is a matter of such serious and interesting consideration, that it cannot be too earnestly recommended to those who make economy in the support of their families an object of their attention.

The chief, and indeed the only thing necessary to be done, is to direct a proper mode of using it to advantage; and this mode is both simple and easy. Care must be taken in filling the digester, to leave room enough for the steam to pass off through the valve at the top of the cover. This may be done by filling the digester only three parts full of water and bruised bones or meat, which it is to be noticed are all to be put in together. It must then be placed near a slow fire, so as only to simmer, and this it must do for the space of eight or ten hours. After this has been done, the soup is to be strained through a hair sieve or cullender, in order to separate any bits of bones. The soup is then to be put into the digester again, and after whatever vegetables, spices, &c., are thought necessary are added, the whole is to be well boiled together for an hour or two, and it will then be fit for immediate use.

From ‘Warne’s Model Cookery and Housekeeping Book’. London, Frederick Warne & Co., 1865. Rouse Hill House collection, Sydney Living Museums

A brief aside

While I was writing this post I noticed that – true to form for so many 19th century publications – that the exact same description from Warne’s appears in both the contemporary The American Home Cookbook (New York, 1864) and the later The new cyclopaedia of domestic economy and practical housekeeper (&c)’ (Connecticut, the Henry Bull publishing Co., 1872). Once you start recognizing text, you’ll realise its being re-hashed and plagiarised continually, even 50 years or more later. The challenge is finding the original.

‘Dem bones, dem bones

The digester is actually far older than the 19th century. It was invented by a French physicist, Denis Papin (1647 – 1713), in 1679. Key to his invention – which he published as “The New Digester”, was an improved pressure valve, which would release excess steam and prevent any awkward explosions. The name of the apparatus came from the action of the high-pressure environment on the bones placed within, which were broken down – or ‘digested’ – releasing their nutrients.

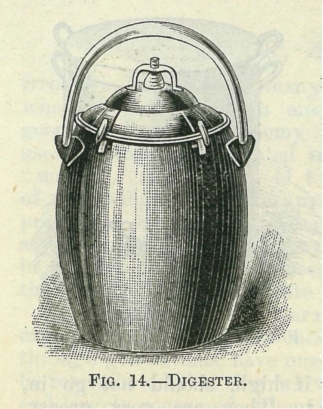

This later example from Cassels (Melbourne 1899) is just a variation on the earlier design published by Warne’s, indicating the basic design didn’t really change over the decades: a tall vessel that has a tightly secured lid. The author Lizzie Heritage neatly describes its purpose: to force out under pressure all the nutrients in meat, bones and bone marrow – you’ll quickly realise that what she’s talking about is ‘bone broth’:

To extract all the goodness from bones in the making stock, a digester is necessary, and will be found a most economical investment in institutions where cooking is done on a large scale and the bones are sufficient in quantity to justify this effort cooking. Few people realize the full measure of nutriment derivable from bones, because the time necessary to extract it is so seldom given… The reason is that the gelatin which is the object of the cook to extract, is so encased in its earthly covering, but the temperature should be high, and pressure is necessary, and only by the aid of a digester is all the soluble matter drawn out.

Shop!

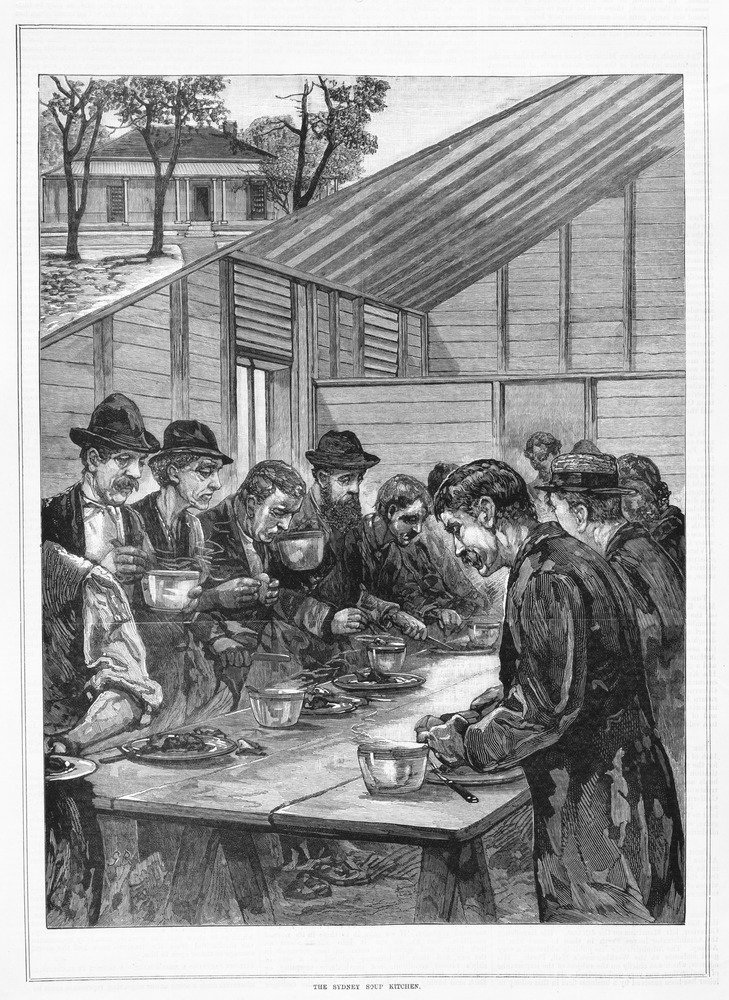

In colonial newspapers, digesters are included in lists of kitchen equipment — “… stewpans, saucepans, kettles, fish kettles with strainers, digesters, kitchens, wash basins, coffee pots and coffee mills” ran one Sydney advertisement in the Gazette, December 1819. In British and American publications, digesters appear frequently in discussions of soup kitchens and other charitable institutions, as well as low-income households. In 2016 Kim Connor wrote about similar cooking in her 2016 post on the Hyde Park Barrack destitute asylum. For the fit-out of a charity kitchen to feed the poor in rural villages, The Social Science Review (London, 1864) recommended:

Each Kitchen should consist at the least of a small range, and a small copper, or digester, or both; with such other additions as would be required for ordinary cooking purposes. The first cost of furnishing would be from £10 to £20. The sum of £10 will furnish a village Kitchen with everything required—including a three-guinea close range, a four-gallon digester, and a strong eight-gallon copper. The sum of £20 will furnish a town Kitchen on a more extensive scale, including a six-guinea close range, two four-gallon digesters, and a strong sixteen-gallon copper.

In larger, urban soup kitchens the digesters and boilers held huge quantities – over 80 gallons each. One huge digester could be accompanied by half a dozen or more boilers or finishing the soup. In 1847 a soup kitchen opened in Dublin, part of efforts to alleviate the terrible famine. It used a mobile cooking mechanism designed by Alexis Soyer, incorporating a variation of the digester concept. A report was quoted in the Australian press:

The building, which is constructed of wood, is about forty feet in length, and thirty feet in breadth, and consists of one large apartment, where the preparation and distribution of the food is effected. In the centre… is a large steam boiler, mounted on wheels, and arranged round the apartment are a number of metalic box-shaped vessel-, also mounted on wheels, into which the materials for the soup are placed. These are heated by steam, conveyed by means of iron pipes from a central boiler, and by slow digestive process, the entire of the nutriment

contained in the materials is extracted without having its properties

deteriorated.

‘Irish Intelligence’; The Hobart Guardian, 11 August 1847

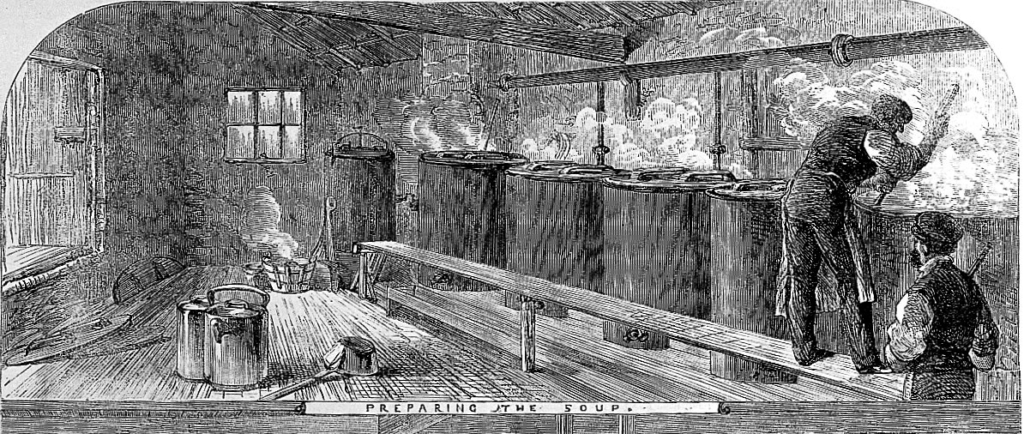

The very large soup kitchens in London and elsewhere used digesters as the first stage in a cooking process that is essentially the same as described in Warnes, though on an industrial not domestic scale: pressure cook the bones, offcuts and offal, then add vegetables and grains to the extracted broth and cook again. Mmm yum! In this detail (above) of an 1862 view, the large cylinder at the left rear with the curved clamp on its top is the digester, the 6 remaining vats are for boiling up the finished soup.

Domestic digesters?

Writers advocated the digester for poor households as a way of getting every last bit of nutrition out of household scraps, but they were in themselves expensive items, and so out of reach of that very market. A heavy soup pot with a tight fitting lid – that could be weighed down to secure extra pressure – was the economic alernative.

To wrap up, here’s a rather horrifying – and yes, thankfully a satirical – account of a soup kitchen being set up in Hobart in June, 1831:

“TO CONTRACTORS AND OTHERS. WANTED to erect immediately for the reception of paupers, about to be transported here, a row of Alms houses, together with suitable residences for the pauper Governor, pauper Superintendents, pauper Deputies, Overseers, Cooks, Scullions, &c. &c. The site of the intended buildings has been most judiciously laid out adjoining to the public slaughter-house, where the facility is so great of conveying all the heads, plucks, and offal of every description into the soup kitchens, which, with the well appreciated thickening gelatinous qualities of the town ditch water, will, it is presumed by the Committee, aided by the voluntary subscription of garbage of one kind or other about the town, be sufficient to support these wretched creatures without drawing on the Commissariat…. [Signed] – GEORGE STARVE-THEM-ALL, Secretary. June 28, 1831”.

[Hobart] Colonial Times, June 29, 1831.

Second helpings

A very thorough paper I came across while writing this weeks post is Soup and Reform: Improving the Poor and Reforming Immigrants through Soup Kitchens 1870–1910, by Philip Carstairs, published in the International Journal of Historical Archaeology in 2017. You can read it online here. Brace yourself for the line “..large pipes emptying into a long trough on the ground floor…”