When you read 19th century cookbooks the terminology can be unfamiliar. Take this definition of stewing: “the act or operation of seething, or boiling slowly.” [1] Boiling sure, but ‘seething’?

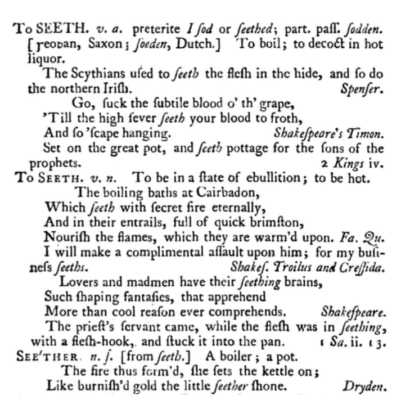

Words, as I (yes, very frequently) point out, can have very blurred definitions. ‘Seething’ is a term we’d use now to define an emotional state of barely-controlled rage. Historically, however, it was a cooking term. He of the famous dictionary, Samuel Johnson [1755], defined it as to boil; to decoct in hot liquor, and refers to the pot used as a seether. As he provides literary evidence for his definitions, he then quotes the poet John Dryden : The fire thus form’d, she sets the kettle on; Like burnish’d gold the little seether shone [2]. If you think of a furious person, red-faced and with cartoon-like steam coming out of their ears, you get how the word evolved to the modern meaning.

By the 1870s it seems to have dropped out of culinary use:

SEETHE – to boil. A word in common use before French cookery introduced the bouillir.

Charles Mackay, ‘Lost Beauties of the English Language’. New York, 1874.

A seething pot

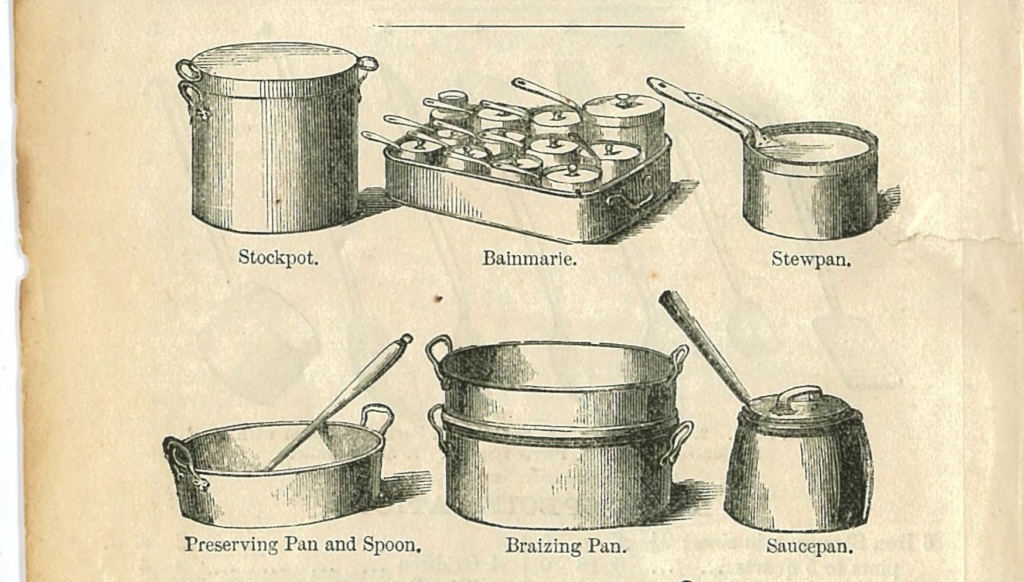

Since this series of posts is all about identifying the contents of a colonial kitchen, what exactly is a stew pot? This detail from Francatelli shows the defining characteristics of the main pot forms: in contrast to a ‘saucepan’ whose sides flare inwards, or a ‘kettle’ where they flare outwards, a ‘stewpan’ is distinctly straight sided, and it has a close fitting ‘cover’ (the lid) to keep in the steam and stop the contents from drying out as they ‘seethed’:

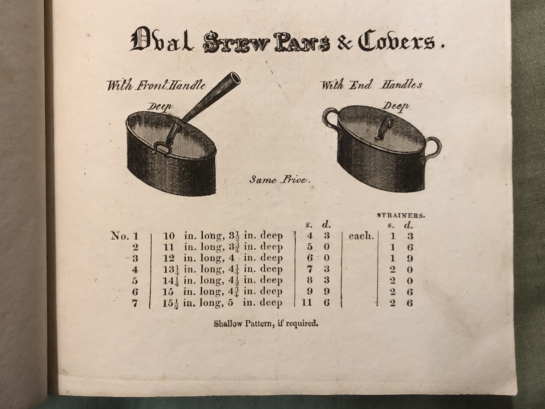

They can be round or oval in shape, as with this example from Vaucluse House – which just to be confusing could also be used as a fish kettle for small fish:

…and they can be huge! This stewpan from Vaucluse – which surely couldn’t be lifted when full – could be used for stewing whole joints or fowl:

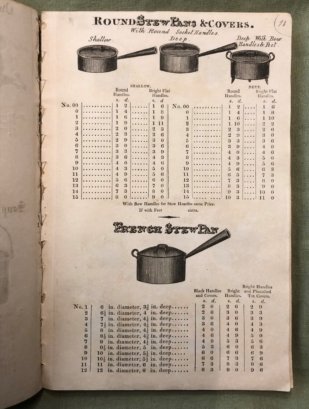

Stewing on an electric stove is quite easy – you just turn down the heat and walk away. On a gas stove you need to be more careful, as a very low flame can blow out, and you may also need a diffuser to avoid too concentrated a heat source. On a closed coal range you moved the pot off the high heat to the side. If – as at Elizabeth Farm – you were using an open, wood-fueled hearth however, then a stew could be made in a high sided pot that had feet or that sat on a raised platform, such as an iron trivet, and typically sat over hot coals dragged to one side of the main fire. You can see an example in the Barns’ catalogue, below, at top right. That way the meat placed in the cooking liquid simmered, but never boiled. You had to keep an eye on it though, to make sure of a constant heat.

‘Wholesome, convenient, and economical…’

Eliza Acton (Modern Cookery, 1845 edn.) wrote of stewing:

STEWING. This very wholesome, convenient, and economical mode of cookery is by no means so well understood nor profited by in England or America as on the continent, where its advantages are fully appreciated. …[If] the process be skilfully conducted, meat softly stoved or stewed, in close-shutting, or luted vessels, is in – every respect equal, if not superior, to that which is roasted; but it must be simmered only, and in the gentlest possible manner, or, instead of being tender, nutritious, and highly palatable, it will be dry, hard, and indigestible.

…Thick, well-tinned iron saucepans will answer for all the ordinary purposes of common English cookery, even for stewing, provided they have tightly-fitting lids to prevent the escape of the steam; but the copper ones are of more convenient form, and better adapted to a superior order of cookery.

A well-luted pot

Since I’m on a roll with definitions… a ‘luted’ vessel? This is also a very rarely heard term, and one that suggests Renaissance music rather than cooking. Websters Dictionary (1828) explains:

LU’TING, noun [Latin lutum, mud, clay.] Among chimists, a composition of clay or other tenacious substance used for stopping the juncture of vessels so closely as to prevent the escape or entrance of air.

LUTE, verb transitive To close or coat with lute

…so to ‘lute’ a cooking pot means using a substance such as pastry (‘paste’) or clay to create a seal around the join between the vessel and the lid. This was a way of turning even a dodgy, badly made pot into a very serviceable stew-pan.

‘A good English stew’

To finish, here’s Acton’s recipe for ‘A Good English stew’. It’s a basic recipe, and any number of variations can be made, by adding pepper, bay, tomato paste, onions and carrots, red wine, you name it:

Ingredients (extrapolated from Acton’s directions)

1.4 kilos beef, cubed into 5cm squares. Rump seems very excessive for stewing, so try shin or chuck, or the round cuts, but not too lean!

1.1 ltrs water or, far better, stock;

Teaspoon of salt, and also of cayenne pepper;

Grated skin of a large lemon, and juice of half;

Tablespoon rice flour in half a cup of water;

Splash of soy sauce;

130 mls white wine or port.

Method (as per Acton’s directions)

On three pounds of tender rump of beef, freed from skin and fat, and cut down into two-inch squares, pour rather more than a quart of cold broth or gravy. [Bring to a heat and] When it boils add salt if required, and a little cayenne, and keep it just simmering [i.e drop the heat right down immediately] for a couple of hours; then put to it the grated rind of a large lemon, or of two small ones, and half an hour after stir [in]to it a tablespoonful of rice-flour, smoothly mixed with a wineglassful of mushroom catsup, a dessertspoonful of lemon-juice, and a teaspoonful of soy: in fifteen minutes it will be ready to serve. A glass and a half of port, or of white wine, will greatly improve this stew.

References

[1] Joseph Worcester, A Dictionary of The English Language. London, Sampson Low, Son & Co., 1859

[2] From Dryden’s translation of ‘The Story of Baucis and Philemon’ from Ovid’s Metamorphoses, quoted in Johnson’s Dictionary, 1755. Baucis and Philemon were poor peasants who, obeying the ancient laws of hospitality, gave shelter to two travelers who had been turned away by all others. As is the way with such stories, the travelers were – surprise! – actually Zeus and Hermes (the ‘denial of hospitality and its repercussions’ trope was firmly established in ancient literature). For the two poor peasants the story ends very well, as their hovel magically turned into a stupendous temple over which they were appointed custodians; for their inhospitable neighbors, not so well, as they were all drowned in a flood sent by the two very displeased gods.