As 2012 draws to a close, I’ve had the opportunity to reflect on how dramatically our food culture has altered, almost in perfect parallel with our social culture, by comparing culinary texts from 1812 and 1912.

A letter of advice – 1812

We’re fortunate to have a letter of ‘advice’ that was sent to Maria Macarthur of Parramatta in 1812, later published into a little book in 1979. The book is a transcription of a letter written by a ‘Mrs E’, titled Advice to a young lady in the colony. The production values of the 70s may make it seem rather outdated but its provenance means that it is a wonderful resource, offering us a glimpse of social protocols and attitudes in the Regency period, and it provides continued inspiration.

Mrs E is understood to be Mrs Samuel Enderby, Maria’s godmother. Maria was Governor Phillip Gidley King’s daughter, born on Norfolk Island but returned to England as a child, who developed a very close relationship with her godmother. Maria later married Hannibal Macarthur (John Macarthur’s nephew) and returned to the colony where, at the age of 19, she was about to take up residence at ‘The Vineyard’, a property neighbouring Elizabeth Farm.

The original manuscript letter is in a private collection, but a copy of it is kept at the Mitchell Library in Sydney. Mrs E went to great lengths to direct the young house-mistress on how to entertain at home in a manner that would suit her status and impress her guests with the latest London ‘society’ practices. Not only does she offer tips on running a household and managing servants, but she also outlines menu plans for a myriad of domestic occasions, from family dinners to a ‘sociable sandwich’ and a ‘grand dance’. As was typical of that time, the menus are given according to their style of service – mapped out on the page according to where each dish should be placed on the table. We’ll explore this practice in future blog posts, but certain dishes stand out on the menus that typify the era, albeit on refined tables.

One hundred years and counting – 1912

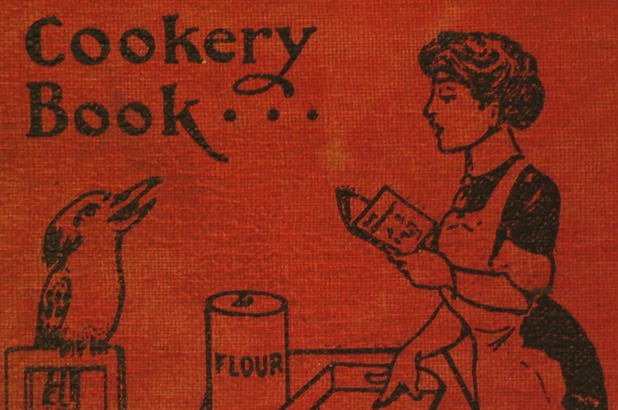

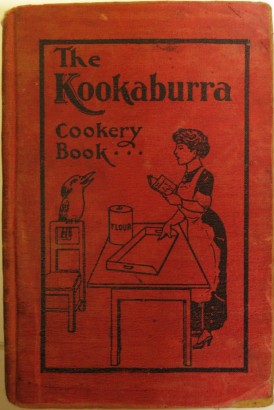

Earlier this year I was invited to speak to members of the Queen’s Club in Sydney, which was celebrating 100 years of service to its members. I was delighted be involved in developing a centenary luncheon menu for the Club, that reflected tastes in 1912. As no known menus or food service records from the club survive, I consulted menus from that period in the ephemera collection at the Mitchell Library and contemporary cookbooks, including the 1912 edition of the Kookaburra Cookery Book. While the object of the exercise was to identify what and how people ate a hundred years ago, and note how our tastes and culinary practices had changed in that time, it struck me that the 1912 menus were, surprisingly, not dissimilar to those proffered in Mrs E’s 1812 letter, both in the types of dishes and the order in which they were served.

Today we would find these one hundred year old menus quaint or nostalgic and many of the dishes would appear very ‘ordinary’, ‘conventional’ or ‘old hat’, but Mrs E would have found them quite familiar. However, she may have been disappointed at the reduced level of staff to assist in table service à la Russe (which The Curator will explore at a future opportunity), even in an upper class home. The meal started with soup then fish, followed by a healthy selection of meat, poultry or game dishes in the form of roasts, pies, ragouts and curries, not unlike a formal à la carte restaurant menu today.

In 1812, curry – which we’ll explore in more detail next month – was new and exotic, found only on elite tables. By 1912, curry powder was the universal seasoning of the day, jazzing up soups, mornay sauces and omelettes. Going by the Kookaburra Cookbook, almost anything could be made into a curry including radishes, walnuts and even peaches! In 1912 India was still part of the British Empire; Pakistan had not been annexed, with the British ‘Raj’ a legacy of the Victorian period.

Offal has faded from our domestic repertoire today but features widely in both 1812 and 1912 menus, ox-tongue in particular. Similarly, game meats such as duck, pigeon and rabbit appear almost as frequently as chicken. In fact, the range of foods available and commonly consumed was much wider than ours today – unless you are a gourmet cook, you’re now limited to conventional butchers’ meats: beef, lamb, pork and chicken. And, if you’re a supermarket shopper, your fish choices are also very narrow.

Jellies were still highly celebrated – both sweet and savoury. In 1912 macedoine vegetables, peas and small prawns, along with cubes of chicken or ham, were set in aspic in decorative moulds while jellied beetroot and puréed tomato bejewelled salads. Jellied eel, tongue and brawn were mainstays for a cold collation in both 1812 and 1912.

Fruit ices (which were very new in 1812), wine jellies and blancmanges and vanilla creams have nowadays given way to sorbets, foams, mousses, coulis and pannacotta. Jelly is now children’s fare and icecream is a no-brainer, always at hand in the domestic freezer. Semolina and sago/tapioca were once pantry staples for puddings, whereas they now only seem to be found in Middle Eastern and Asian desserts, respectively. However we find bread puddings and charlottes reappearing as comfort food on restaurant menus today.

What’s old is new again – 2012

What has obviously changed in Australian cuisine is its multicultural diversity, made possible by immigration and facilitated by modern agricultural, transport and refrigeration innovations, along with television, which has exposed us to all manner of cultures and cuisines. Yet, for all our improved access to the myriad of foods available and modern conveniences, there’s a resurgence of interest in traditional, artisan and bespoke practices.

While award winning chefs such as Heston Blumenthal (The Fat Duck, UK) and René Redzepi (Noma restaurant, Sweden) excite contemporary diners with culinary innovation and concoctions never dreamed of, it is interesting to remember that even domestic cooks 200 years ago were playing with texture and flavour (recall the 18th century bacon and eggs in flummery in last month’s post). Domestic cooks were also naturally resourceful, using wild and native ingredients such as elderflowers and game. In Australia, sometimes driven by necessity but also by curiosity, people were openly experimenting with native flora and fauna, concepts we will continue to explore in The Cook and the Curator into 2013.

Sources

Advice to a young Lady in the colonies. Barca, Margaret (ed). Greenhouse Publications Pty Ltd. 1979

The Kookaburra Cookery Book of culinary and Household Recipes and hints. The Lady Victoria Buxton Girls’ Club, Adelaide, South Australia. 1912