While we’re mainly looking at the pots and pans in this series on the colonial batterie de cuisine, it’s a good time for a diversion into all the miscellaneous bits and pieces in a kitchen – all those things we keep in the ‘third drawer down’.

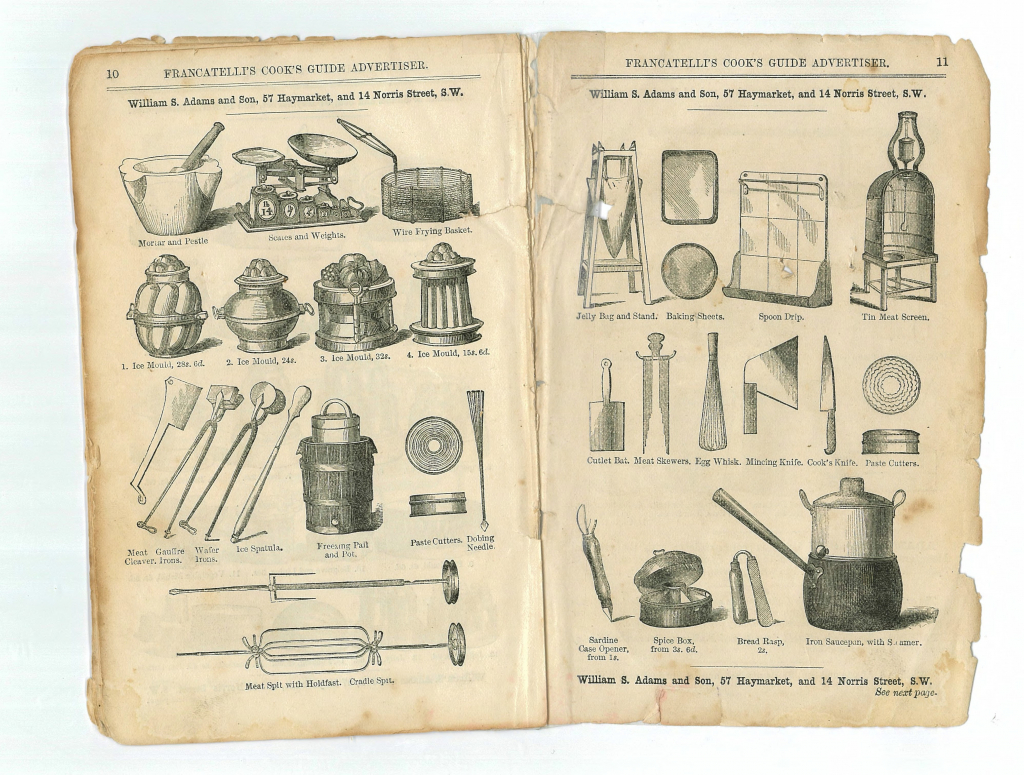

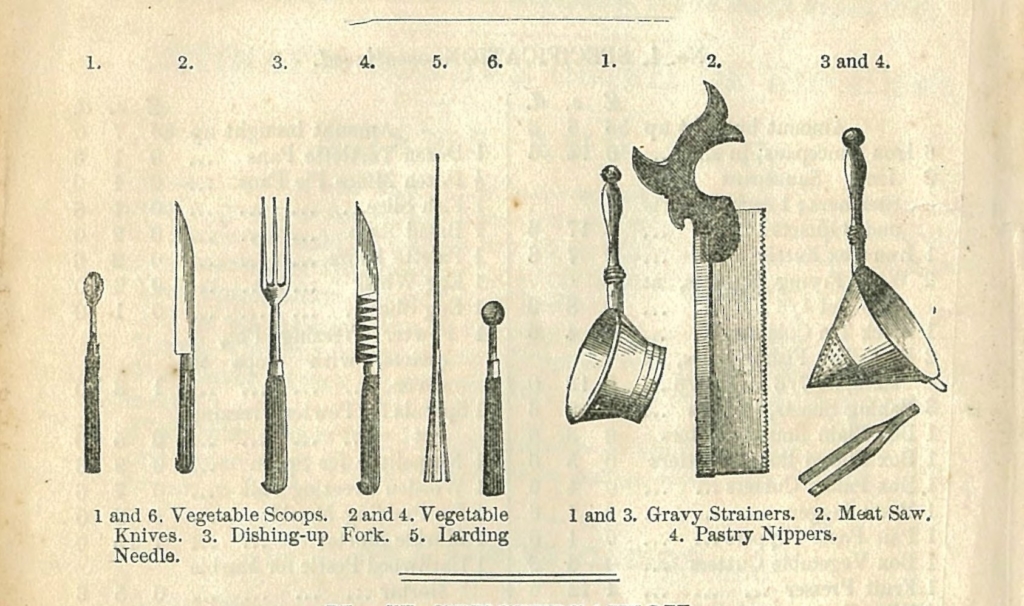

The auction and trade catalogues we looked at last week certainly contained pots and pans, – and fish kettles! – but they also list the many smaller things, all the utensils that a cook might need. This page from Francatelli’s catalogue illustrates a whole batch of necessary items: from a mortar & pestle and jelly bags, to knives, spoons and ladles, pastry cutters and spice boxes:

The kitchen from scratch

A lot of 19th century household and servants’ guides, whilst providing a wealth of information on household economy, are of far less use when it comes to the requirements for actually fitting out a kitchen. Anne Cobbett’s ‘The English Housekeeper’ (London, 1835), while it doesn’t give lists, and starts out singularly unhelpfully by saying such lists are ‘impossible’, does go on to provide a practical rebuttal of the popular image of the showpiece-kitchen:

It is impossible to give particular directions for fitting up a kitchen, because so much must depend upon the number of servants employed in it, and upon what is required in the way of cookery. It was the fashion formerly to adorn the kitchen with a quantity of copper sauce-pans, stew pans, &c. &c. very expensive, and exceedingly troubling to keep clean. Many of these articles which were regularly scoured once a week, were not, perhaps, used once in a year.

Whole generations of kitchen maids crouched over stone sinks just cried ‘hallelujah!’ Rather than go for show, she advises, the homemaker should consult the cook who will use them as to what they actually need.

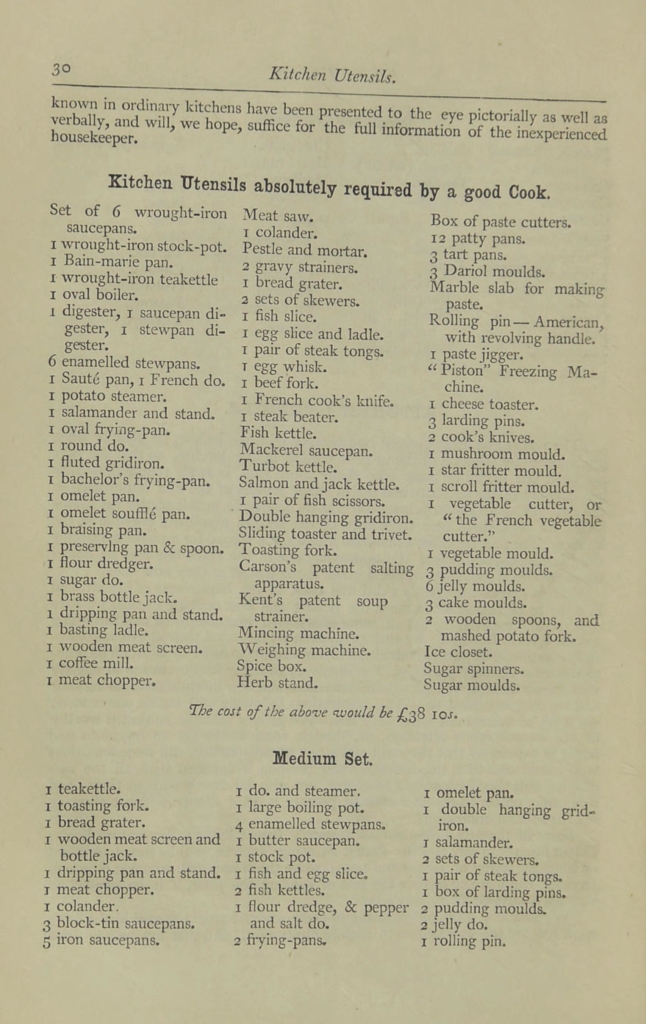

Kitchen utensils absolutely required by a good cook!

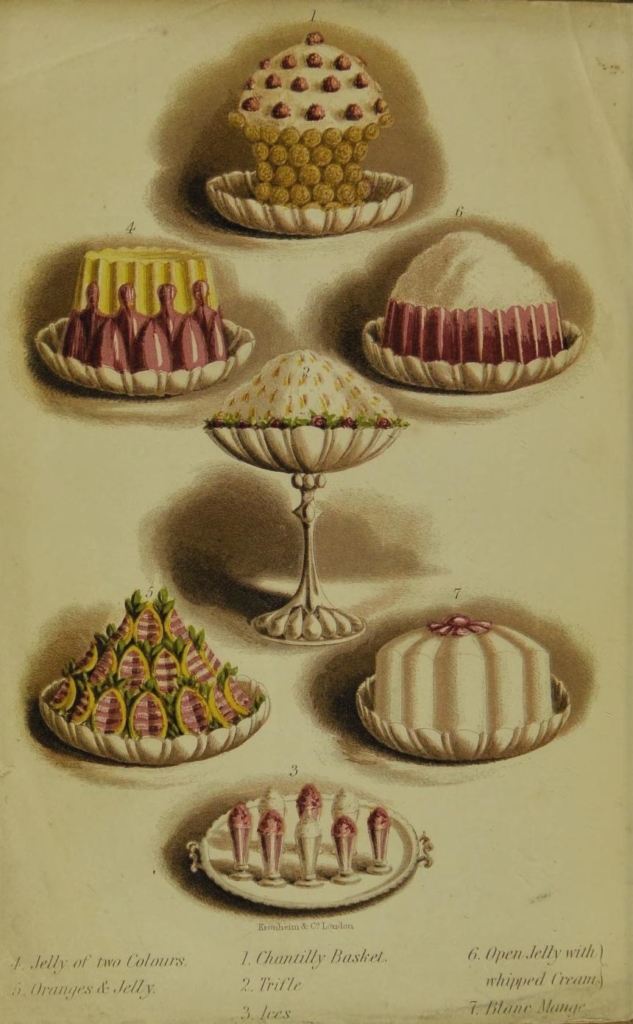

Warne’s Model Cookery and Housekeeping Book (“contains complete instructions for household management”), which is contemporary with Cobbett, does provide lists comparable with the fit-outs of the Sydney kitchens discussed in my last post. Its frontispiece of jellies and blancmanges has little to do with this – but it’s rather wonderful so I’m including it. Long term followers of the blog will spot the ribband oranges at bottom left:

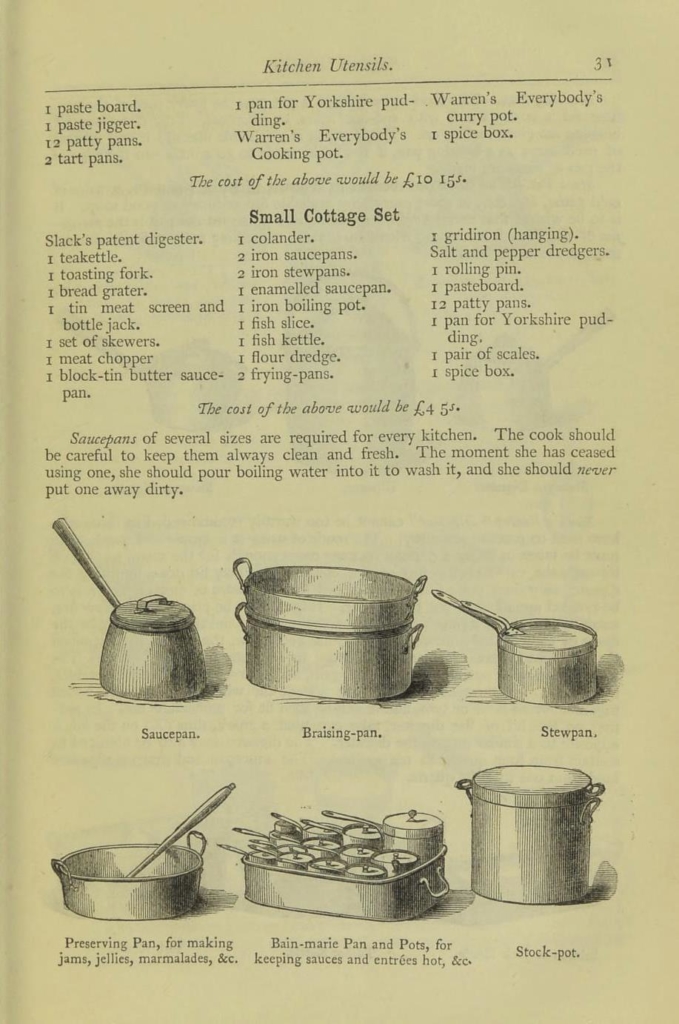

Warne’s included 3 lists for differing sized household. If we take the number of post and frying pans we’ve decided on for well-to-do households like Elizabeth Farm or Vaucluse as a guide, then a mix of lists no.1 and 2 would be applicable:

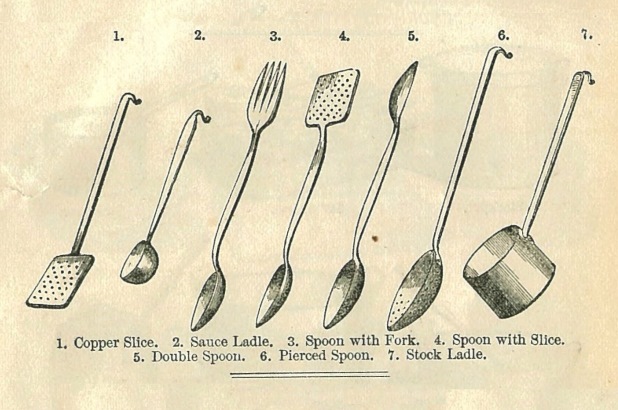

The odd omissions between the lists stand out to me – and again, especially the peculiar knife situation. While the first includes 2 cooks’ knives and a vegetable cutter, the second only includes only a ‘meat chopper’ – a cleaver. List one contains “2 wooden spoons and a mashed potato fork”, while list two only contains a rolling pin. Likewise, compared to the Francatelli catalogues you note that the Warne lists are also missing spoons, ladles and sieves. Their absence does not of course imply that they were not used. Feathers for example, which could be used as a pastry brush, appear nowhere in any list.

Second helpings

Warne’s Model Cookery Book is online here

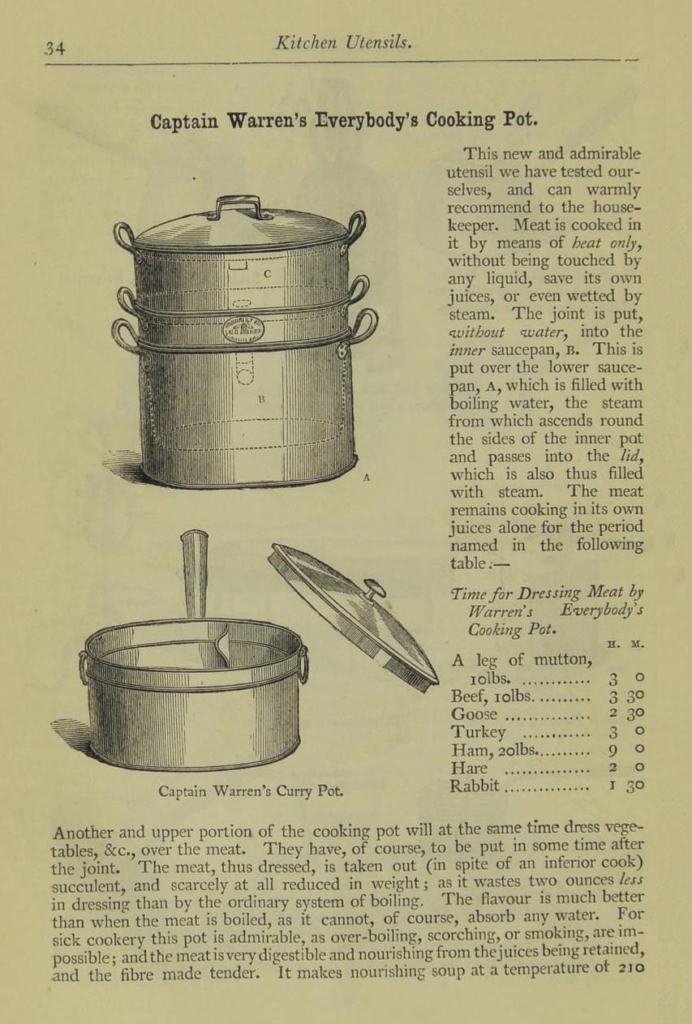

The studious and attentive Servant will have noted “[Captain] Warren’s Everybody’s Cooking Pot.” This egalitarian item was essentially a ‘pot within a pot’ – an inserted upper chamber held the meat. It was sealed from the lower, which contained water that was boiled. Steam circulated around the upper chamber, heating it so that the joint cooked “in its own juices”. An extra layer could be added that contained vegetables, added about 2/3 through the cooking process – and hopefully not scalding the cook terribly when it was opened: