Now that we’re expert in the fine art of roasting, lets try our hand at broiling!

Broil: To drefs or cook by laying on the coals, or before the fire. Samuel Johnson, 1755.

You probably don’t realise it, but many of us use this technique routinely – at the barbecue! [1] While today its meaning is confusing in a geographical context, historically broiling is simply a form of grilling over an open flame, using a slatted surface such as a hand-held gridiron. Beeton describes the process:

Broiling is an excellent mode of cooking tender, juicy meat, from the best joints, fish, &c., but it is not suited to other kinds… To broil successfully there must be a hot, clear fire, to start with, so that the albumen [proteins] of the meat, suddenly heated, becomes hardened and a crust is formed which effectively retains the juice. The gridiron should be hot and well greased. …the food should be turned often with tongs or some instrument that will not make new holes or cut. [2]

Today the words broiling and grilling are highly interchangeable, often depending on which country you’re from and whether you’re referring to heat ‘from above’ or ‘below’. A quick web search will give you no end of pages debating the terms. Johnson (1755) quotes the use of the word by Dryden in his translation of Virgil’s Aeneid:

Some strip the skin, some portion out the spoil… some on the fire the reeking entrails broil.

Very much a barbecue. In 1906 The Book of the Home, published in London, used both words effectively for the same process, albeit with a subtle phrasing suggesting that broiling used heat from in front (i.e. that the meat was hung, but not constantly rotated like a roast) or above “in the case of a gas or electric stove”. In 1909 Cassell’s Household Cookery decided the difference was in fact the angle of cooking, whether it was vertical (broil) or horizontal (grill), and used direct or radiant heat respectively:

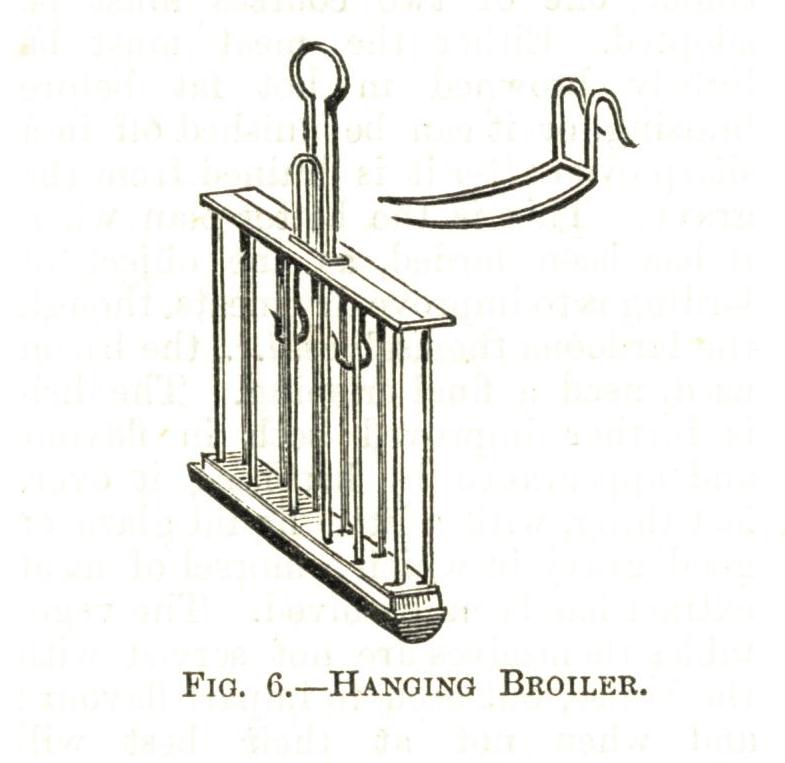

Broiling is quite distinct from grilling, though the two terms are frequently regarded as synonymous. The result is totally different for a grill has a sweetness which no broil possesses (due mainly to the contact with the fire, and the consequent retention of the gravy [i.e. the meat juices]. Broiling is also convenient, and needs comparatively little attention; it is economical too, as its answers for small joint, birds &c., less fire being needed than would suffice to heat a side oven for baking them. There are many varieties of hanging broilers or toasters; the best, for good sized pieces of meat are the double ones, with a fitted tin pan underneath as illustrated:

‘Hanging broiler’ illustrated in Lizzie Heritage, Cassell’s household cookery, Cassell & Co., Melbourne, 1909. Caroline Simpson Library & Research Collection, Sydney Living Museums 641.5 HER

In this illustration, the nasty-looking hooks attach directly on the top of the grate, and the slatted basket is hung on them, the hooks sliding in under the top horizontal leaving the handle above clear. In Emma Rouse’s 1863 edition of Mrs Beeton’s Book of Household Economy, the ‘beaten-up-Beeton’ in the Rouse Hill collection, is this method of broiling steaks, complete with a sophisticated French title for your tastefully written menu cards:

BROILED BEEF-STEAKS or RUMP-STEAKS

(Fr.- Bifteck a l’Anglaise)Mode.- As the success of a good broil so much depends on the state of the fire, see that it is bright and clear, and perfectly free from smoke, and do not add any fresh fuel just before you require to use the gridiron. Sprinkle a little salt over the fire, put on the gridiron for a few minutes, to get thoroughly hot through; rub it with a piece of fresh suet, to prevent the meat from sticking, and lay on the steaks, which should be cut of an equal thickness, about three quarters of an inch, or rather thinner, and level them by beating them as little as possible with a rolling pin. Turn them frequently with steak tongs (if these are not hand, stick a fork in the edge of the fat, so that no gravy escapes), and in from 8 to 10 minutes they will be done. Have ready a very hot dish, into which puts the ketchup, and, when liked, a little minced shalot; dish up the steaks, rub them over with butter, and season with salt.

The exact time for broiling steaks must be determined by taste, whether they are liked underdone or well done; more than from 8 to 10 minutes for a steak three quarters of an inch of thickness, we think, would spoil and dry up the juices of the meat.

Gridiron from the Vaucluse House collection, and used in the Curio Wall in the Eat Your History exhibition. Sydney Living Museums V81/36

This gridiron, from the Vaucluse House collection, has splayed back feet that can be rested on the top bar of the grate while in use. Mary Radcliffe adds one important note for broiling: “Observe never to baste anything on the grid-iron, because that may be the means of burning it, and making it smoky.” (A Modern System of Domestic Cookery, Manchester, 1823, p43). In other words, adding drippy liquids causes a flare-up, as any good barbecue aficionado will tell you.

In All about Cookery and other works by Beeton there are several recipes for ‘broiled beef’ served with rich sauces. In most however it is cold cooked beef that is used, leftovers from a previous roast, which is reheated and given extra flavour by broiling and then being served with a sauce. This thrifty use of leftovers to avoid waste pervades all of Beeton’s guides. Typically her weekly menus are arranged to utilise the remains of grander meals. Similarly, in Mrs Maclurcan’s Cookery Book (Sydney, 1909), broiling is often given as a finishing element after a much longer process; in her recipe for broiled beef palates for instance the palates are soaked for an hour, boiled for three hours, the crumbed and broiled for a far shorter 5 minutes at the end before serving. Fish can also be broiled; Maria Rundell (A New System of Domestic Cookery, London, 1808) advises wrapping a well buttered piece of salmon in paper so it wont stick to the gridiron, and serving with an anchovy sauce. [3]

And a sauce to serve with your beef-steak?

Oyster, tomato, onion, and many other sauces are frequent accompaniments to rump-steak, but true lovers of this English dish generally reject all additions but pepper and salt. [Beeton, 1863]

This recipe for steak with a mushroom sauce also comes with ‘serving suggestion’:

Beef, broiled, and Mushroom Sauce.

INGREDIENTS- 2 or 3 dozen button mushrooms, 1 oz of butter, salt and cayenne [pepper] to taste, 1 tablespoon of mushroom ketchup, mashed potatoes

Wipe the mushrooms free of grit with a flannel, and salt; put them in a stewpan with the butter, seasoning and ketchup; stir over the fire until the mushrooms are quite done, when pour it into the middle of the mashed potatoes [which is arranged as a ‘bowl’ shape in the centre of a plate], browned.Then place round the potatoes slices of cold beef, nicely broiled over a clear fire. In making the mushroom sauce the ketchup may be dispensed with , if there is sufficient gravy. [1]

Bon appétit!

Notes

[1] For our international readers, a reminder that this blog uses Australian terminology with a heavy dose of 19th century prose. The rather fantastic image at the top is by Adrian Wiggins, and was taken at a Sydney Living Musuems: Food event at the Hyde Park Barrack in 2013. It featured a rustic barbecue made from reinforcement mesh and corrugated iron.

[2] Mrs Beeton’s All About Cookery, c1900, from Jacqui’s collection.

[3] Mary “what me, rip of someone else’s title?” Radcliffe gives this recipe for broiled salmon with an anchovy sauce.

Ingredients: Salmon fillets, butter, flour, salt, 2 whole anchovies, a leek, capers, pepper, nutmeg, lemons to garnish.

“To broil fresh Salmon. Cut some slices from a fresh salmon, and wipe them clean and dry; then melt some butter smooth and fine, with a little flour and basket salt Put the pieces of salmon into it, and roll them about, that they may be covered all over with butter. Then lay them on a nice clean gridiron, and broil them over a clear but slow fire. While the salmon is broiling, make your sauce thus: take two anchovies, wash, bone, and cut them into small pieces, and cut a leek into three or four long pieces.

Set on a sauce-pan with some butter and a little flour, put in the anchovies and leek, with some capers cut small, some pepper and salt, and a little nutmeg; add to them some warm water, and two spoonfuls of vinegar, shaking the saucepan till it boils; and then keep it on the simmer till you are ready for it. When the salmon is done on one side, turn it on the other till it is quite enough; then take the leek out of the sauce, pour it into a dish, and lay the broiled salmon upon it. Garnish with lemons cut in quarters.”