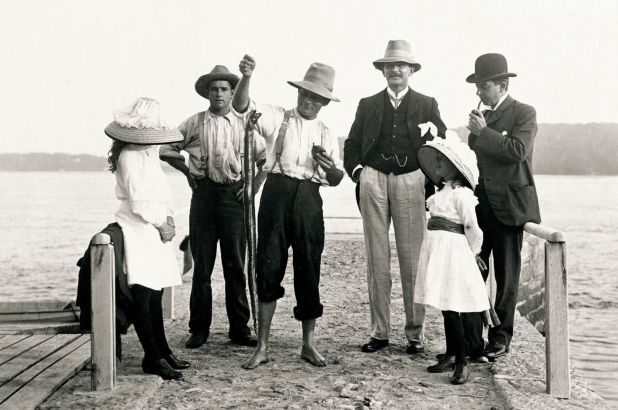

As we gear up for this year’s Eel Festival at Elizabeth Farm on Sunday 3 March, we are exploring the various ways that eels were cooked and eaten in the past. We have no indication of what became of the eel in the above image from the early 1900s – was it grilled, stewed, crumbed and fried or ??

So far we’ve enjoyed eels freshly roasted by Fred from Fred’s Bush Tucker (see below) smoked (more on this next time) at our Eel Festivals, and I’ve also tried collared eels and jellied eels, following English traditions (which I’d deem tasty, but not as enjoyable as the former options). Then there’s the way that most Australians might sample eel these days, at sushi bars which served ‘grilled’ eels which are imported ready-marinated in soy sauce and sugar.

Coal roasted eel using indigenous bush tucker methods at the Eel Festival at Elizabeth Farm. Photo © James Horan for Sydney Living Museums

Eeeuw yuck!

But cooking eels is one thing – preparing them for cooking is quite another! And I’m speaking from experience. Eels are naturally slippery and slimy, a natural characteristic of their composition. Whenever possible I buy eels from a restaurant supplier, which have conveniently been cleaned and de-slimed. But there was a time when I had to buy them straight from the tank in Chinatown, to make collared eel for a media interview, which was quite a different kettle of fish (err, eels!)

The ‘eeeuw’ factor was high (on my personal scale), but the process was a real education for me as a gastronomer. I developed a much deeper appreciation of what is involved to prepare eels for the table – especially when freshly caught – a process that many more accomplished cooks than I, past and present must have experienced. It’s certainly not a task for the squeamish amongst us, and although I’m a bit of an adventurous cook I’d be happy if I’m not required to repeat it any time soon! So be warned, the details below may not appeal to some of our readers…

Festival visitor Bruce Zellie with eels in the aquarium at the 2018 Eel Festival at Elizabeth Farm (detail). Photo © Alex Wisser for Sydney Living Museums

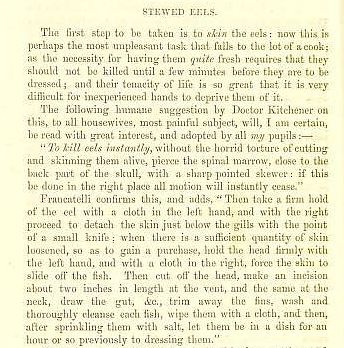

The Tickletooth method

Needless to say I declined the offer of taking the eels home alive in a bag of tank water and let the fishmonger ‘dispatch’ the glistening black creatures with great efficiency. It appears that this part of the process was a matter of concern for cooks in past times. According to the wonderfully named Tabitha Tickletooth (pseudonym for cookery author Charles Selby) in The Dinner Question “they should not be killed until a few minutes before they are to be dressed; and their tenacity of life is so great that it is very difficult for inexperienced hands to deprive them of it.” The author the proceeds to give detailed advice about the quickest and most humane method.

Instructions from ‘Tabitha Tickletooth’ for preparing eels for cooking in ‘The Dinner Question’ by or Charles Selby, 1860. Accessed via archive.org

The lot of the cook

“The first step to be taken is to skin the eels [which] is perhaps the most unpleasant task falls to the lot of the cook…”

Many other recipes advise that the skin should be removed, thankfully, as I consider skinning an eel is well beyond my skill set – I’d end up with raggedy scraps of eel rather than a neat long fillet. And the skin on the restaurant standard eels was clean and although sticky, relatively easy to work with and not unpleasant to eat.

Cleaned eel ready for culinary use. Photo © James Horan for Sydney Living Museums

Unpleasant indeed

Not so the live eels’ I purchased on this occasion, which were a Tasmanian species. Despite rinsing the eels under running water and wiping them with paper towel, my hands were covered in black slime that was extremely difficult to remove. Soap and hot water had no impact, and just slid off; paper towels stuck in clumps to my hands and had to be rinsed off under running water; a cloth tea-towel was a little more successful in getting the gooey slime off, but not all of it. In the end I resorted to scraping the excess gunk off with a pallet knife and washing my hands in a vinegar solution to cut through the persistent sticky residue.

Sadly I’d not yet discovered Mrs Tickletooth’s advice, which she gleaned from Queen Victoria’s chef Charles Francatelli, to handle the eel with a layer of cloth over the skin, but worked this out myself the hard way. (The tea-towel I used also had to be washed in vinegar). Only then was I able to proceed with collaring the eel…

Rolling the seasoned eel fillet for collared eel Photo © Amanda Ho, ABC News Radio Online