There’s a special pleasure in tasting a fruit straight from the tree. Just a few months ago, the cherry guavas in the kitchen garden at Vaucluse House were tiny, unpromising-looking green orbs. This week, the first of them ripened: little rose-coloured marbles of sweet-tart deliciousness, each a perfect mouthful – and the perfect ingredient for a clear fruit jelly.

A consignment of fruit trees

In 1846, William Charles Wentworth bought a selection of fruit trees, grape vines and ornamental plants from William Macarthur’s famous nursery at Camden Park and planted them in the garden at Vaucluse House. [i] Among them was a Cattley’s purple guava (Psidium cattleyanum), also known as the strawberry or cherry guava.

Remains of the orchid house at Camden Park – part of a complex of hothouses at William Macarthur’s famous 19th-century nursery. Photo Helen Curran © Sydney Living Museums

Cherry guavas ripening on the tree in the kitchen garden at Vaucluse House, September 2015. Photo Helen Curran © Sydney Living Museums

Originally from Brazil, the cherry guava had arrived in Australia by 1831, and was soon being lauded as ‘an excellent fruit, [which] bears most abundantly’ (Sydney Morning Herald, 26 February 1841). Despite its name, the cherry guava doesn’t taste like a cherry at all – or a strawberry for that matter. Here’s the English Magazine of Domestic Economy attempting to pin down that elusive flavour in 1840:

The berry is round, of a beautiful mulberry purple colour, about the size of a large gooseberry, which fruit it much more nearly resembles in flavour than that of the strawberry … It differs, however, totally from either of these berries in the skin, which is like that of the orange, with little cells containing an essential oil, and this gives a peculiar aromatic flavour, not only pleasant but unique.

The most delicious conserve

Nineteenth-century English readers were reliant on such descriptions. In Australia, cherry guavas grow freely in the open air, but in England they were limited to those in possession of a hothouse or conservatory, and few were in a position to sample the exotic fruits straight from the shrub. Instead, the passion was for guava jelly, imported from the British colonies in the West Indies and sold at enormous prices.

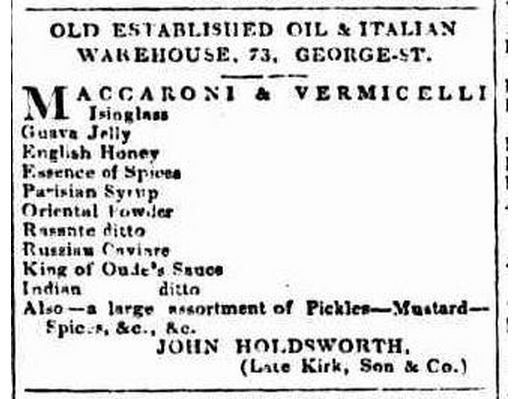

Guava jelly was a luxury item in mid-1800s Sydney too, given head billing in the newspaper advertisements of the city’s importers. In 1838, you could buy it from the Italian warehouse at 73 George Street – and while you were there, stock up on ‘English Honey’, ‘Parisian Syrup’, ‘Russian Caviare’ and ‘King of Oude’s Sauce’.

An advertisement for guava jelly in the Sydney Monitor, 12 October 1838.

Unlike their English counterparts, Australian cooks were able to experiment with making guava jelly themselves. In March 1918, the Sydney Morning Herald reported that cherry guavas were selling at sixpence a box – ‘[not] cheap enough to make [them] suitable as a preserving fruit … but those who are fortunate enough to possess a tree or two will find … that guava jelly is one of the most delicious conserves of all’.

This isn’t the boxed, powdered jelly to be found at birthday parties and buffets, of course, but the real deal: fruit stewed with water, strained through fine muslin, and the liquid boiled with sugar until it reaches setting point. The result is a darkly glowing red jelly, like the jar that Jacqui was kind enough to give me.

A jar of Jacqui’s guava jelly, made from the cherry guavas at Vaucluse House. Photo © Helen Curran

The trouble with sticky fingers

Homemade guava jelly was exhibited at Sydney’s floral and horticultural shows throughout the 1840s – to the fury of one of the Sydney Morning Herald’s correspondents.

An 1847 letter from ‘David Decorous’ protests the inclusion of jellies and preserves at the city’s flower shows. The writer is particularly aggrieved by young ladies dipping their fingers into the jars of candied peaches and quince marmalade. He lays the blame squarely on a Mr Staddon, whose preserves were, it seems, particularly irresistible: ‘His guava-jelly [is] incomparable at a dessert or in diffusing a benign influence over a bowl of whisky punch’.

Yep, David’s a classic curmudgeon. But his grumpy tirade holds a clue to why guava jelly was so popular: during the 19th century, it was used as an ingredient in both trifle and the dessert known as ‘floating island’.

Unlike French îles flottantes (poached meringues floating in custard), the floating island found in Britain and her colonies featured various sweetmeats atop a syllabub-like concoction. This dish, sampled by the British writer Frederic Bayley, is typical:

There is a made dish in the Antilles, called floating island, which is very luxuriant, and a great ornament to the dessert or the supper table. A sort of pond composed of wine, sugar, citron, and cream, but principally of the latter ingredient, is contained in a large glass, and surrounds a little island of guava jelly, which is seen floating on the top.

Frederic William Naylor Bayley, Four Years’ Residence in the West Indies, 1833

David’s letter also suggests another popular colonial use for guava jelly: for a time, it was considered indispensable in making punch.

Oh! ye gods, what punch!

In 1845, the weekly Sydney newspaper Bell’s Life published a recipe for punch, drawn from a Canadian travelogue. A small pot of guava jelly, dissolved in a pint of boiling water, was added to a pint of freshly brewed green tea along with plenty of lime-infused sugar. The final touch – six glasses of cognac, two of Madeira, a bottle of rum and ‘the slightest possible sprinkling of nutmeg’.

Here was the punch; and, oh! ye gods, what punch! … Whether it was the tea, the limes, or the Guava jelly I will not pretend to say, but, the truth must be told, [we] were very curiously ‘bosky’ [tipsy] by ten oclock …

Is this what William Charles Wentworth had in mind for his cherry guava he ordered from Camden Park the following year? We’ll never know! But I’ll be trying a (modified, responsible!) version with the rest of Jacqui’s gorgeous jelly as soon as the occasion arises.

Cherry guava jelly

You won’t find cherry guavas in the markets these days, as the fruit has a short window of ripeness. As one of our horticulturists, Anita Rayner, told me: ‘It’s all or nothing with the cherry guava … you’ve got to get them when they’re red enough for the flavour to be at its peak, but before they become too soft.’ But you may find a tree: the cherry guava has become naturalised in some parts of the country.

Jacqui made her guava jelly by substituting cherry guavas for lilly pilly berries in her recipe for lilly pilly jelly. You’ll find it contains helpful advice for avoiding a cloudy jelly and for determining when setting point has been reached.

You could also try this recipe, which appeared in the Goulburn Evening Post in 1927.

Select the purple guavas when just ripe – not overripe. Allow a pint of water to four of fruit and cook gently with the lid on the preserving pan for about 15 minutes. Remove the lid and continue cooking for another 15 minutes or so. Strain the juice, measure it and allow an equal measure of sugar to that of juice. Boil very rapidly for 1o minutes, until the jellying stage is reached.

The verdict – delicious. Photo © Helen Curran

—Guest blogger Helen Curran is an assistant curator at Sydney Living Museums

[i] When the Historic Houses Trust re-created the kitchen garden at Vaucluse House in 2000, this receipt from Camden Park was one of the key pieces of evidence for what would have been growing in the mid 1800s. A cherry guava has also been planted in the garden at Elizabeth Farm.