Last year we talked about those confusing and interchangeable words baking and roasting, and got to grip with table- and soup spoons. They’re far from the only confusing words used in the historic kitchen and household, so today I’m starting a series of posts looking at the vast range of pots and pans you can see in a historic kitchen – and what exactly they were called and used for.

Whats in a name?

Names for household objects can vary widely from those we use today, and a 19th century dictionary is a valuable resource for the researcher. When I wrote my thesis I actually had a copy of Johnson’s Dictionary on my desk. A few years ago I wrote a definition of the words ‘couch’ and ‘sofa’ as used in the early 1800s, using historic definitions. I include it here because it still gives me a chuckle [1]:

Of all the names for domestic furniture, be they modern or historic, perhaps the most confusing terms are ‘couch’ and ‘sofa’. At the time of their introduction to English they appear as seemingly freely interchangeable terms, subject to the whims of fashion and the individual preference of chair makers, retailers and purchasers, and indeed their mixed usage today is much the same. The entry for Johnson’s Dictionary (1st edition) shows that by 1755 ‘sofa’ had not yet entered the English vocabulary and still referred to its original meaning, that of the continual seating that lined the walls of a Turkish diwan, or reception room: “Sofa: [I believe an Eastern word.] A splendid seat covered with carpets”. Couch however has a clearly established meaning: “Couch [from the verb]; a seat of repofe [i.e. repose], on which it is common to lye down dressed.” The second edition (1827) provides the updated but singularly unhelpful definition of sofa as “a couch”, which is in turn defined as a “seat of repose; a bed”.

So basically, “sofa, see couch’, and ‘couch, see sofa’… and don’t get me started with ‘lounge’!

The ‘B.d.C’

Part of the batterie de cuisine at Vaucluse House. Photo (c) Scott Hill, Sydney Living Museums

Back in 2012 we looked at the ‘batterie de cuisine‘, a phrase you’ll often hear in a historic kitchen. Though the term today is not often heard outside of professional kitchens and house museums, every household has one. It simply refers to the moveable collection of pots, pans and equipment used in a kitchen (not the stove, sink or large appliances). When you look at the 19th century kitchen however, the variety of shapes and sizes can be bewildering, and each had its specific name and nominated use. So lets start at the very beginning – with boiling water, and the ‘kettle’.

Polly, put the kettle on!

Aluminium kettles on the stove at Meroogal. (C) Sydney Living Museums. Detail of photograph by John Storey

‘Kettle’ is a name that has kept its basic meaning but today become defined to a specific item – the handled and spouted container, either plugged in or placed on the stove-top, that you boil water in. As a word it began with the Latin catinus (a bowl), then meandered through Old English with cetel, Middle English ketel and the Scandinavian kettil and kessel. A kettle is essentially a container used to boil liquid; usually, but not always, water. While foodstuffs such as fish can then be placed into it (hence ‘fish-kettle’), it’s the purpose of boiling the water that defines the vessel. Samuel Johnson [Johnson’s Dictionary of the English Language, 1755] defined it:

Kettle. A vessel in which liquor is boiled. In the kitchen the name of pot is given to the boiler that grows narrower towards the top, and of kettle to that which grows wider. In authors they are confounded.

In early colonial newspapers the most common kettles mentioned in advertisements are ‘tea kettles’ – namely those familiar, top-handled pots with a long, narrow upwards pointing spout, used to boil water which could then be poured into a teapot. While the iconic kettle has a bright shiny copper exterior, black iron-kettles were far more hard wearing (and heavier). They’re often quite large, holding several liters.

Copper kettle at Throsby Park. Sydney Living Museums, detail of photograph (c) Doug Riley

For heating a much larger quantity of water, there is the ‘tea boiler’. Webster describes them: “Tea boilers are made of cast iron, and hold two or 3 gallons of water [roughly 15 1/2 liters, so very heavy when full] wanted for tea; they are detached vessels, and, being boiled over the fire in the range, are kept hot upon the hob; they have a cock to draw off the water.”

A tea boiler in the scullery at Vaucluse House. Photo (c) Scott Hill for Sydney Living Museums

It highlights a basic fact: in an era before gas, electricity and the ‘insta-boil’, hot water had to be kept ready at all times in case it was needed. If you had to start from scratch, you could be waiting a considerable amount of time for that pot of tea.

The ‘fish kettle’

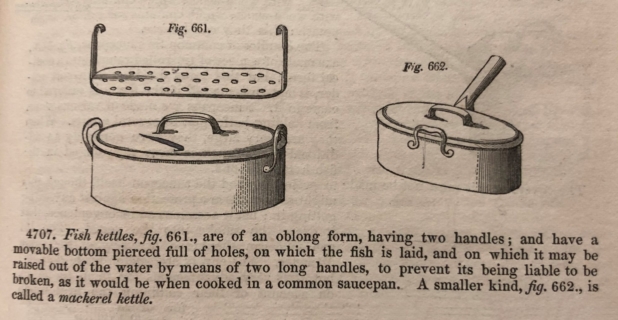

The next kettle the ads mention is the distinctively shaped ‘fish-kettle’, which Beeton defines:

FISH-KETTLES are made in an oblong form, and have two handles, with a movable bottom, pierced full of holes, on which the fish is laid, and on which it may be lifted from the water, by means of two long handles attached to each side of the movable bottom. This is to prevent the liability of breaking the fish, as it would necessarily be if it were cooked in a common saucepan. [Household Management, 1865 edn.]

Beeton’s text is lifted straight from Thomas Webster (1847), who illustrated two common forms:

Fish kettles, from Thomas Webster’s Encyclopaedia of domestic economy. London, 1847

A pair of pots similar to what Webster calls a ‘mackerel kettle’ are in the kitchen at Vaucluse House. Around 20cms wide, and with long handles distinctively to one side, they could be used for poaching smaller fish:

Small fish kettles at Vaucluse House. Photo (c) Scott Hill for Sydney Living Museums

…while a larger pot, around 50cms long, easily functions as a kettle for larger fish, such as snapper or a large bream:

Oval pot from the batterie de cuisine at Vaucluse House. Photo (c) Scott Hill, Sydney Living Museums

You’ll notice I haven’t definitively called these two ‘fish kettles’, or even ‘kettles’, and there’s a reason. For the vast bulk of 19th century kitchens this degree of specialization – typified by the kite-shaped European ‘turbot kettle’ – just didn’t happen. The vast array seen at Petworth (an awe-inspiring thousand pieces!), or in the made-for-tv kitchen of Downton, were costly in the extreme. The large pot shown above – which Webster (1847, p821) calls a “kitchen boiler or kettle” – was used just as well for a large joint of meat such as mutton or beef. Beeton stresses that “the kettle in which a joint is dressed should be large enough to allow room for a good supply of water; if the meat be cramped and be surrounded with but little water, it will be stewed, not boiled” [Household Management, 1861].

Without the handled lift shown by Webster, a piece of muslin could be used to lower and lift a fish just as well. With a large kettle such as this a colonial Sydney household could enjoy a dish such as this poached snapper served with cucumber scales, part of a reconstruction I did at Vaucluse House some years ago:

Poached snapper ready to serve at Vaucluse House. Detail of photograph (c) Cath Muscat for Sydney Living Museums

You get a kettle, and you get a kettle – everyone gets a kettle!

Naturally there are more:

GLAZE-KETTLE. — This is a kettle used for keeping the strong stock boiled down to a jelly, which is known by the name of glaze. It is composed of two tin vessels, as shown in the cut, one of which, the upper — containing the glaze, is inserted into one of larger diameter and containing boiling water. A brush is put in the small hole at the top of the lid, and is employed for putting the glaze on anything that may require it.

GRAVY-KETTLE. — This is a utensil which will not be found in every kitchen; but it is a useful one where it is necessary to keep gravies hot for the purpose of pouring over various dishes as they are cooking. It is made of copper, and should, consequently, be heated over the hot plate, if there be one, or a charcoal stove.

[Isabella Beeton, The Book of Household Management, 1861edn.]

Another ‘kettle’ mentioned in the ads is a ‘try-kettle’. One was auctioned in 1803, salvaged from a shipwreck. Better known as try-pot, this was a considerable size, and used on board ship for boiling down whale or seal blubber for oil. Its name (try = tri) is derived from its 3 feet, which gave it stability on deck. There’s one in the scullery at Vaucluse House.

Salmon in court bouillon

This illustration from ‘Artistic Cookery: A Practical System Suited for the Use of the Nobility and Gentry’ (1870) shows fish cooked in a fish kettle, including one (the fish at top) you can try at home: salmon poached in a court bouillon stock. This is a classic stock, easy to prepare and use.

Plate 7 from Artistic Cookery: A Practical System Suited for the Use of the Nobility and Gentry, by Urbain Dubois. London, Longman Green and Co., 1870.

Salmon served in court-bouillon

The salmon represented in the drawing is cut, and boiled in a court-bouillon; this is certainly the fittest mode of cooking it; but salmon boiled in a ‘court-bouillon’, ought to be served as soon as done, to be eaten hot; if it remains in the liquid, or if served half cold, it cannot but lose its good qualities. It would be better to eat it quite cold.

To prepare salmon, cut in slices, and boiled in a ‘court-bouillon’, it must first be scaled; when the slices are cut, they must be well cleaned, then set on the drainer of a fish-kettle with the head and tail; then the fish must be covered with a sufficient quantity of cold ‘court-bouillon’ of wine; the kettle is then set on the fire, till it boils; then put beside the fire, but kept covered: in ten minutes the slices are done.

To make a court bouillon, combine the following:

3 3/4 liters cold water

1/2 a liter white wine

50 mls lemon juice

700 g mirepoix

4 bay leaves

4 crushed peppercorns, crushed

1 pinch dried thyme

1 bunch parsley stems, torn

1 tbsp salt

A mirepoix is itself a classic mix: use a mix of 1 part each diced carrots and celery, to 2 parts diced onions. In a large pot bring the whole mix up to a high simmer, then drop to a simmer for another 3/4 of an hour. Strain the liquid through a colander, then again through muslin to leave a clear stock. This makes a decent quantity, so you’ll have some to freeze for later use. Any cookbook will give you a recipe.

Place the fish, or fish fillets, single layered in a kettle or broad pot, cover with the simmering court bouillon, and keep at a simmer for a few minutes. Drop the heat to a low simmer and poach another 10 minutes or until cooked, perhaps 15 for a whole salmon. Use a slotted spatula to lift from the stock, and pat dry. Serve immediately, or if not, as Dubois suggests, cold. You could also use the stock for poaching chicken.

[1] Yes, this a good example of ‘curator humour’.