Mmmmm, syllabub! Surely one of the best things about syllabub is its name – just saying it is fun! Syllabubs are yet another ‘ lost’ dessert – quite decadent, alcohol fueled and deliciously rich, with a long history.

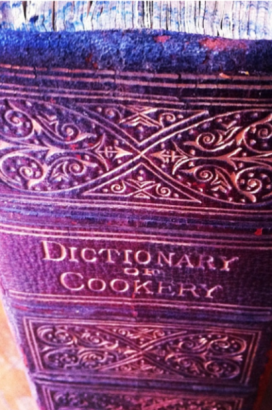

One of our team, Sarah Fitzherbert, Editor at Sydney Living Museums, has her grandmother’s cherished edition of Cassell’s Dictionary of Cookery from the 1880s. It claims to contain over 9,000 recipes but, not surprisingly, it was the recipe for ‘syllabubs under the cow’ that her family took great delight in discovering!

The delight in this recipe is, of course, the idea that you would take your punch bowl, half-filled with grog, out to your cow – because of course every household had one – and a dairymaid to tend it!

Syllabubby history

I’ve had a long fascination with syllabubs – they date back at least to the 16th century, and their form and flavour has gradually changed over time. Early recipes reveal it as a product of natural alchemy – fresh, unpasteurised milk reacting with the acidic qualities of lemon juice and alcohol (wine, cider, strong beer, sack (sherry) and / or brandy), and sugar. For extra flavour the lemon rind would be rubbed or ‘rasped’ over the rind, as we’ve previously explored in this blog.

Not to be confused with an alcoholic milk punch, which has now been lost to history, syllabubs had a characteristic creamy ‘head’, made by milling or whipping the alcohol infused cream to a rich ‘froth’. The enriched cream would then be ladled into special glass or china vessels which were specially designed for the purpose, then set aside to develop for several hours. As the mixture settled, the richer cream would separate from the other liquids and rise to the top, resulting in a layered concoction – semi solid on top and liquid below. The syllabub would then be served, either to drink or imbibe from a spoon. If the combination of thick and thin seems odd, think of our current predilection for cappuccino coffee, the textural qualities of the rich thick froth with the warm thinner milky liquid below. For for those old enough to remember the 1970s trend for Vienna coffee, or the more decadent Roman or Irish coffees, this receipt comes very close to the mark:

Kitchen alchemy

From analysing various recipes form different texts, the special character of a syllabub from ‘under the cow’ is that the force of the milk directed into the alcoholic mix would create a light bubbly froth on the surface of the mixture. The syllabub ‘head’ would develop ‘alchemically’ overnight as the mixture cooled, with the cream from the milk naturally rising to the top, presumably with the light film of bubbles remaining over it. It seems fairly normal for households to have access to a cow in the 1600s and 1700s – especially as so much of the population lived in rural settings.

What, no cow?

But it is interesting to think this process would still be recommended in Cassell’s publication from the 1880s (those 9000 recipes had to come from somewhere!), with an assumption that people had their own cow and dairymaid. Indeed, some might, but probably only large or wealthy households, or those on rural properties, such as the Rouse family, who had their own dairy cows through to the early C20th.

Clearly some other authors understood that not all would have the luxury of their own cow or dairymaid, providing an alternative technique to similar effect (we presume). Mrs Beeton’s syllabub recipe, for example, is much simplified: she cheats a bit with the addition of clotted cream, but her wording is curious, as she saying ‘milk into it’ – does she mean this as an action, with ‘milk’ the verb? or did she simply mean ‘add milk into it’? But then note the trick with the teapot in the last line…

TO MAKE SYLLABUB.

1486. INGREDIENTS – 1 pint of sherry or white wine, 1/2 grated nutmeg, sugar to taste, 1–1/2 pint of milk.

Mode.—Put the wine into a bowl, with the grated nutmeg and plenty of pounded sugar, and milk into it the above proportion of milk frothed up. Clouted cream may be laid on the top, with pounded cinnamon or nutmeg and sugar; and a little brandy may be added to the wine before the milk is put in. In some counties, cider is substituted for the wine: when this is used, brandy must always be added. Warm milk may be poured on from a spouted jug or teapot; but it must be held very high.

The advice for using warm milk (emulating fresh cow-temperature) being poured from a height, using the spout of the teapot to create extra pressure for sharp delivery into the mixture mimics the fresh milking process. I’ve seen Mrs B credited elsewhere with finding this ingenious solution for the dairymaid-deprived household, but in fact this technique was offered in 1747 by Hannah Glasse and was probably a known household technique even before she published her recipe.

Pink ‘spider’. Photo Toby & K http://inthemoodfornoodles.blogspot.com.au

Spider bait

The taste for these split-textured dishes has all-but disappeared, with the exception, perhaps, for the cappuccino. English food historian Ivan Day suggests that syllabubs, along with many other sweetened dairy desserts, lost their charm as ice-cream making became possible as a domestic craft. After being popular for over 300 years, syllabubs disappeared from our tables. Day’s observation made me think, however, that in fact the original syllabub roots still exist in what we’d know today an ice-cream ‘spider’. The spider has limited popularity in Australia (or perhaps I’ve grown too old for them?); I identify spiders with American pop-culture of the 20th century – Richie Cunningham’s Happy Days ice-cream sodas – rather than being a remnant of seventeenth-century England.

‘Everlasting’ syllabub

With the recent trend towards rediscovering traditional dishes, syllabubs do seem to be enjoying a quiet revival. Our modern idea of a syllabub is closer to what was known as the ‘Everlasting syllabub’ which was also around in the 1700s, where sugar, rubbed over a lemon and alcohol were absorbed into thick cream which would hold its form once well whipped (hence the everlasting), then be laid over the top of sweet red or white wine. Rather than laying it over wine, the alcohol infused cream is ideal for use in a trifle, or makes a decadent filling for brandy snaps. I find sherry generally gives a nicer flavour than wine and the nutmeg is a must! Whipping the cream to a soft consistency before adding the alcohol helps it hold its form.

‘Everlasting’ syllabub

Ingredients

- 300ml pouring (whipping) cream

- 1 tablespoon caster sugar (or pure icing sugar)

- 100ml sweet sherry (or non-alcoholic alternative such as pear nectar)

- 1 teaspoon lemon juice

- 1 teaspoon finely grated lemon zest (optional)

- freshly grated nutmeg (to garnish)

- toasted flaked almonds (to garnish)

Note

This syllabub can be served as is, or with crumbled macaroons or amaretti biscuits sprinkled over the top. It can also be piped into brandy snaps or baskets, or used as the cream layer in a trifle. Use a sweetish sherry or experiment with liqueurs, remembering that their colour will affect the ‘purity’ of the traditional white syllabub. I'm particularly partial to Grand Marnier, for its orange flavour, and hazelnut Frangelico – dilute the liqueur to taste. If you prefer an alcohol-free version, replace the liqueur with fruit syrup or a fragrant elderflower cordial.

Serves 4

Directions

| Using electric beaters, whip the cream and sugar on medium speed until the cream starts to thicken. Reduce the beater speed and, while still beating, add the sherry in a slow steady drizzle. Add the lemon juice and the zest, if using. | |

| Taste for sweetness, and add more sugar if needed. Increase the beater speed until the mixture forms a thick cream (the time will depend on the power of your beaters). Be careful not to over beat, as the syllabub may curdle or split. | |

| To serve, spoon the syllabub into dainty glasses and garnish with the grated nutmeg and flaked almonds. | |

* examples can be found on Ivan Day’s website http://www.historicfood.com/Syllabub%20Recipes.htm

Isabella Beeton, Beeton’s Book of Household Management 1861.

Cassell’s Dictionary of Cookery

‘Spider’ image http://inthemoodfornoodles.blogspot.com.au/2012/12/brisbane-gluten-free-and-vegan-eating.html

Print recipe

Print recipe