At Elizabeth Farm we’re gearing up for the Spring Harvest festival on the 25th of September, and the chard is putting on a fine show!

Spinnage and spinach

SPINACIA, Spinach, or Spinage.

… There are two or three varieties of Spinach cultivated in the kitchen-garden. The common Spinach, intended for winter use, should be sown on an open spot of ground in the latter end of July, observing to do it, is possible, when the weather is rainy. When the young plants are come up, the weeds must be destroyed, and the plants left at about five inches asunder. The ground being kept clear of weeds, the Spinach will be fit for use in October. The way of gathering it to advantage, is only to take off the longest leaves, leaving those in the center to grow bigger and at this rate a bed of Spinach will furnish the table for the whole winter, till the Spinach sown in spring is become fit for use, which is common in April.

‘The Botanists and Gardeners new Dictionary’. James Wheeler, London, 1763

If you were to go to a green-grocer in New South Wales (or Queensland) and ask for spinach what you’d usually be given is actually the much larger-leafed silver beet or chard, specifically Swiss chard. Spinach (which is often termed ‘English’ spinach), and also grown for its leaves, is actually a different plant altogether. [1]

Bunches of English spinach. Photo (c) Scott Hill

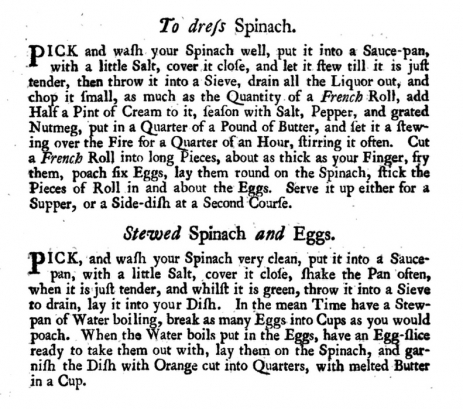

Originating in the middle east the name for this low-growing plant evolved – in the usual roundabout way such words evolve – from the original Persian, ispanak, as the plant moved west. In Latin it became spinacia, in medieval Latin spinachia, in Italian spinacia and Spanish espinaca, in old French espinache (it then wandered off by itself and became ‘epinard’ in modern French), in Old Dutch spinaetse, before becoming spinage in English in the early 1500s when it first appears in cookbooks. [1] The spelling was still in creative flux in the 18th (and indeed through the 19th and even into the 20th) century, appearing as ‘spinage’, spinnage’ and the recognisable ‘spinach’, as in these mid-century recipes by Hannah Glasse for that classic duo spinach and poached eggs:

Spinach recipes from Hannah Glasse’s ‘The Art of Cookery’ (London, 1747, 2nd edn.). Source: Google Books

‘Stewed’ simply means cooked in water, and a stew pan is what we would now term a larger saucepan. (There’s a note on f and s below). Did you notice both recipes make a point about washing the leaves? You need to wash spinach thoroughly as, growing low to the ground, it easily catches grit and dirt between its stems.

‘Round’ and ‘prickly’ spinage (my new favourite word) seeds were included in the First Fleet supplies, and it was grown at Henry Brown Hayes’ garden at Vaucluse House.

Warrigal greens

Warrigal greens in the Vaucluse House kitchen garden. Photo (c) Anita Rayner for Sydney Living Museums

The catch is that ‘English’ spinach really dislikes hot, dry weather, so it didn’t flourish in colonial gardens. There was a local alternative however – Warrigal greens (Tetragonia tetragonioides), also called New Zealand spinage spinach, which thrives in a Sydney summer. When his ship visited New Zealand Captain Cook used the plant as part of his (highly successfull) efforts to prevent scurvy in his crew, and likewise when he realised it also grew around Botany Bay in New South Wales. His journal of the voyage has constant references to the crew being sent to “gather greens”, and seeds were taken to Europe. This 1827 writer to the Hobart Courier seems unaware the plant also grew in Sydney:

We intreat some of the seafaring gentlemen who occasionally traffic between these colonies and New Zealand, to bring with them a few of the most useful native seeds and plants… The new Zealand spinage also (tetragonia expansa) admirably calculated to withstand the hot and dry seasons of this climate, for it produces abundantly during the hottest of the summer months, would supersede the use of the common spinage, which soon burns up. It is already in general use in England and Switzerland.

The Hobart Town Courier, 17 November 1827

Fortunately by cooking it the colonists learned what Aboriginal and Maori people had long known: Warrigal greens / New Zealand spinach contain a natural toxin that is broken down in the cooking process. English spinach however can be eaten raw as a salad vegetable (think of those ubiquitous bags of baby spinach leaves in the supermarket salad aisle).

Warrigal greens running rampant in the Vaucluse House kitchen garden. Photo (c) Anita Rayner for Sydney Living Museums

Quick growing and with a trailing habit warrigal greens is very easy to grow – in fact at Vaucluse House it seems to swamp the beds in the kitchen garden if you turn your back for a few days. It easily tolerates a coastal, salty environment, and likes a moist but well drained soil rich in humus. Like English spinach, all you do is pick off enough stems to provide the leaves you need, leaving the plant in the ground.

Rainbow chard

Ruby chard at left and white stemmed silver beet at right are actually both rainbow chard. Photo (c) Scott Hill for Sydney Living Museums

With its brightly coloured stems rainbow chard is often described as the “poster child of the heirloom vegetable movement”. This one variety can produce stems that are white, pink, yellow or a ruby red:

Yellow stemmed chard at Elizabeth Farm. Photo (c) Scott Hill for Sydney Living Museums

Cooking with spinach and chard

Dishes served with spinach are often described as ‘Florentine’, apparently a reference to Maria de Medici’s – yes, she of the Florentine Medici, and who married King Henry IV of France in 1600 – favourite vegetable. Here she is in a totally gratuitous image:

Maria de Medici loved her spinage! Detail from a portrait by Frans Pourbus or Scipione Pulzone. Source: Wikimedia used under creative commons license.

Makes a change from Popeye. Eliza Acton (Modern Cookery, 1845) gives us a traditional English style of cooking spinach, repeated by Beeton and the other expected authors, and which is also how you can cook chard; pressing the cooked leaves deals with the issue of having the spinach or chard leak hot water all over your plate. While fully grown English spinach isn’t available in every grocer you can use baby spinach, which is just the young leaves of the plant. And yes, you could use chopped frozen spinach:

SPINACH (Common English Mode) Boil the spinach very green in plenty of water, drain and then press the moisture from it between two trenches [you could use two breadboards]; chop it small, put it into a clean saucepan, with a slice of fresh butter, and stir until the whole is very well mixed and very hot… and send it quickly to table.

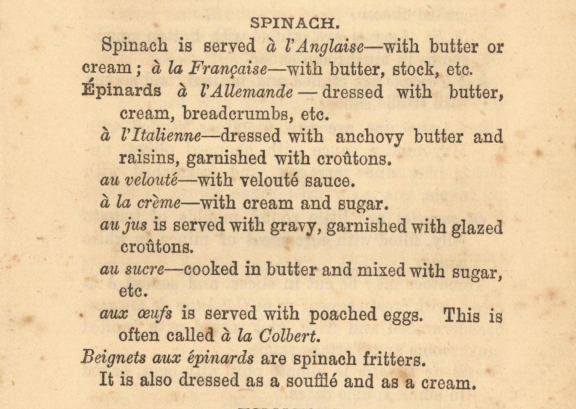

The same method is repeated by other authors including Mrs Beeton. Maria Rundell (A new system of domestic cookery, 1805) added that it then “looks well if pressed into a tin mould in the form of a large leaf, which is sold at tin-shops. A spoonful of cream, is an improvement.” This characteristic creamy addition would later be termed a l’Anglaise:

Modes of serving spinach from Nancy Lake, ‘Menus made easy’ (1903)

This week visitors at a candlelight tour of Elizabeth Farm made the dish, which was then served up at the fully set table. The croutons were made using a biscuit-ring, and I have to say I rather enjoyed it! Serve a crouton to your plate, then add the creamy spinach on top.

Plate of spinach a la Anglais. Photo (c) Scott Hill for Sydney Living Museums

Add the eggs

If you go back to Hannah Glasse’s recipe, she dresses the bed of cooked spinach, which has been sauteed in butter and cream, with poached eggs and finger-thick croutons made from a sliced ‘French roll’ – a baguette. While she suggests it as a second course dish, it would make a very fine breakfast. The trick with her recipe is that when removed from the water the spinach / chard can’t be fully cooked, or it will lose its colour and go mushy when sauteed.

The recipe ‘a la Creme’ in Lake’s guide, which is served with sugar, may jump out; 19th century spinach recipes include cinnamon and other spices. Hannah Glasse’s spinach recipes, such as her ‘spinach pudding’, often include nutmeg and are very mid-Georgian. If you’re after a less sweet dish, try using a good spoonful of sour cream instead of sweet.

Bon appetite!

Notes

[1] The Macquarie Dictionary [Sydney, Macquarie Publishers. 2009, 5th edition], notes that “While spinach and silverbeet are known throughout Australia, there is a distinct preference for spinach in NSW and Queensland, and silverbeet in Victoria, Tasmania and South Australia, for the form of beet.”

[2] see The Shorter Oxford Dictionary, 6th edn.

Nancy Lake, Menus made easy, or how to order dinner and give the dishes their French names. London, Frederick Waren & Co., 1903 (14th edn.)

Hannah Glasse’s typesetter wasn’t having issues that day; the spelling follows a convention where the first ‘s’ in a word usually appears as an ‘f’, the second as a more familiar ‘s’, the first of a pair as an ‘f’. ‘Sucess’ would therefore appear as fucefs – unless the word is spelt with a capital, in which case it is Sucefs. What IS a bit whacky is that some words here DO use an s, like ‘boils’ and ‘dish’. Go figure!

On Sunday, September 25th its Spring Harvest time at Elizabeth Farm! We’ll be talking about it again, but you can read all about the event here.