If pepper is the king of spices and cardamom the queen, cinnamon in my mind, must be the princess – delicate, sweet and fair. And if this were a fairy tale, cassia would be her ‘illegitimate’ step sister … bold and brash, without cinnamon’s grace and refinement.

Barking up the wrong tree?

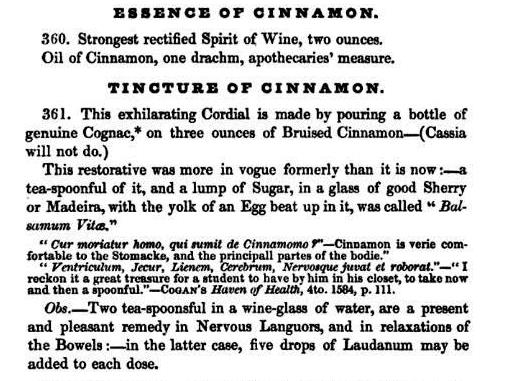

The image above shows two sorts of cinnamon commonly available on the market – ‘true’ cinnamon, Cinnamomum zeylanicum which is native to Sri Lanka and cassia, Cinnamomum burmanii, once known as ‘bastard cinnamon’ which is from south east Asia. Both are derived from processing particular layers of bark from their respective trees. They have a distinguishable difference in aroma and flavour – cinnamon is comparatively mild but has a cleaner sweetness than cassia which is more pungent or aggressive cinnamon-like aroma. It is often difficult for people to discern their differences when purchasing, as some spice companies label cassia as cinnamon. It’s even harder for the untrained eye to work out which type of cinnamon your are buying once the bark has been ground into a powder.

Bastard cinnamon. Curtis’s botanical magazine. 1801. p. 1636. by Bentham-Moxon Trust.; Curtis, William. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew.; Stanley Smith Horticultural Trust.

An endangered art

True cinnamon is the fine under layer of bark peeled from branches from the cinnamon tree, botanical name, Cinnamomum zeylanicum, which is native to Sri Lanka and southern India. (You can see the etimological association between zeylanicum and and Ceylon, the colonial name for Sri Lanka. In some European countries it is still referred to as Ceylonese cinnamon). The art of cinnamon peeling and forming it into fine cigar like quills is an artisan practice, still performed at point of harvest in Sri Lanka. The various steps in the process have been passed on from generation to generation, although the traditional processing is in danger of declining as young Sri Lankans move into better paid, less labour intensive careers. The sensual nature of cinnamon itself is beautifully articulated by immortalised in Michael Ondaatjie’s poem, The cinnamon peeler.

Innocent cousin or impostor?

Cassia, sometimes known as ‘bakers cinnamon’, ‘bastard cinnamon’ and ‘Dutch cinnamon’ is cheaper to produce and process than true cinnamon, being one thick curl of much harder bark (noticeable in the foreground of the image above). Each tree gives a greater product yield involving far less specialised labour than true cinnamon. Cassia is therefore more attractive for commercial food producers – it’s the ‘cinnamon’ found in commercially made cinnamon buns and scrolls, raisin breads and the now ubiquitous cinnamon ‘donut’. Once ground into powder form, true cinnamon loses its ‘oomph’ more readily than cassia, which remains quite pungent after processing, another reason it is favoured by commercial food manufacturers – giving more ‘bang for the buck’ and therefore more economical.

With slow cooking, true cinnamon remains sweet, where the bolder characteristics in cassia tend to dominate other ingredients. So as a rule of thumb, choose true cinnamon for more delicately flavopured dishes – poached fruit, custard and rice pudding, rice and couscous dishes for example, and cassia for bolder flavours – Asian soy-sauce marinades or mulled red wine; use it sparingly in biscuits and cake recipes.

Packaged cinnamon sticks, Niru Brand, Canada. Note that the image on the packet shows cassia rather than ‘true’ cinnamon. Image source: Niru Enterprises website

“Cassia will not do.”

So, what’s the big deal you ask? They both taste of cinnamon so does it really matter? At the end of the day, its a matter of taste and our tastes are generally influenced by what we know, what we’ve been brought up with, and what our palates have been trained to tell our brains is right.

When trying to replicate historical recipes it is very difficult to determine which cinnamon has been used by which cooks and for which dishes. The most telling clue may come from regional politics and colonial territory, according to the origin and period of your recipe (see my potted history theory below). I have found only one ‘receipt’ that distinguishes between the two, Dr Kitchener’s Apicius Redivivus, or The Cook’s Oracle, first published in 1815. According to the eminent physician, ‘cassia will not do’ when making a tincture of cinnamon (one wonders if those suffering ‘nervous langours’ would notice the difference once the five drops of Laudanum are added – under the good doctor’s orders!)

Tincture of cinnamon. Dr William Kitchener. The Cook’s Oracle. Cadell 1836. p. 269

Another case of mistaken identity

‘Tejpat’ leaves from the cinnamon tree also have a culinary use, and are the reason that some Anglicised recipes call for European style bay leaves. Cinnamon and cassia both belong to the laurel or Lauraceae family so when Indian recipes were appropriated by the British they used the closest species they could find locally. Tejpat, or ‘Indian bay’ leaves have three ribs (shown in the botanical illustration above) and a much more delicate flavour than the very savoury European bay, but if you’d never tried a ‘real’ curry made with cinnamon leaves, how would you know?

Spice wars

The confusion lies in history (of course!) from a time when the Dutch and the English were vying for hegemony in India, Sri Lanka and south east Asia. To simplify a period of great political and economical complexity, you have two trading companies, the Dutch Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie (VOC – United East India Company) and the British East India Company (BEIC). By the late 1700s the English were gaining power in China and India but the Dutch had control of Sri Lanka, known then as Ceylon AND the Spice Islands in the Molucca Straits and a global trading port in Batavia (now part of Indonesia). This gave them a monopoly on Sri Lanka’s cinnamon and the Spice Island’s nutmegs, cloves (until Pierre Poivre and friends interfered – see last week’s Peter Piper’s peppers post) and the locally grown cassia. Dutch ‘Spekulaas’ biscuits are the legacy of this rich and exotic blend of ‘sweet’ spices. But in the late 1790s the English gained control of Sri Lanka, and along with it, direct access to cinnamon, leaving the Dutch out in the cold. From then on, the Dutch traded predominantly in cassia, which became known as ‘Dutch cinnamon’, and cassia remains today the common cinnamon in northern Europe and the USA – who had no desire to trade with the English having just gained independence. Cassia also grows in Vietnam and was known as ‘Saigon cinnamon’ until the 1970s when the moniker lost its gloss… but that’s yet another chapter in history…

sources and further reading:

Herbie’s Spices – what’s the difference between cinnamon and cassia?

Ian Hemphill, The spice and herb bible Published by Robert Rose Inc. Ontario, Canada

University of Ruhuna Faculty of Agriculture. Cinnamon processing and quality assessment.

Curtis’s Botanical Magazine, 1801

Cinnamon sticks image Niru Enterprises, Canada. http://niru.ca/product/cinnamon-sticks/