‘Let them see how like England we can be’

Following on from last week’s post about The Australian International Exhibition 1879-1880, the event was highly lacking in local flavour (a condition that many would argue is still the case today)…In the words of scholar, Graham Pont, ‘the colonial food exhibited at the Garden Palace was British, boring and unimaginative’ [1]. The various spice companies – which included the Mackenzies brand which still survives today, may disagree, albeit showcasing spices that suited English tastes, including the ubiquitous ginger, cloves, mixed spice, mustard and curry powders. The closing line of part one of Kendall’s cantata (purposely omitted from last week’s post) continued with what we might now regard a rather – dare I say – pathetic and cringe-worthy desire for emulation of the ‘Mother Country’.

Shining nations! let them see

How like England we can be… [2]

One does wonder (or wish) perhaps, if the author could have enjoyed being a little snide in this sentiment – which would have been quite a coup in having it immortalised in the opening ceremony, but testament to the final phrase, very few uniquely Australian foods were exhibited.

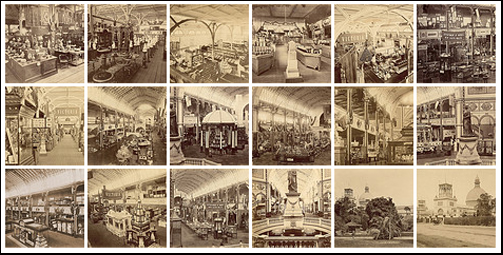

The Garden Palace, interior view ‘East Transept, (from the Dome)…’ Richards & Co. 1880. Image courtesy NLA obj-140660512. Note the cones of ‘loaf’ sugar on the Colonial Sugar Company display.

Dugong bacon, anyone?

Exceptions generally had a mercantile trade rather than taste ring to them: ‘splendidly preserved’ Moreton Bay ‘Turtle in shell’ won a First degree in Merit; ‘lard’ and ‘bacon’ from Queensland dugong, smoked beche-de-mer – ‘trepang’ or ‘sea cucumber’ – albeit prepared the way Timorese had done for centuries [3].

Salt bush lamb – how very 21st century!

‘Salt bush, salsolaceae’ gained special mention in the ‘Aboriculture and Forest Products’ section, species of which ‘to the pastoralists in Australia are practically invaluable’ as a grazing feed, due to its drought-resistant hardiness [4, 5]. Salt bush lamb and mutton have become quite a ‘thing’ in recent years, revered by discerning meat consumers. In the land so often disparaged for having mutton, mutton, mutton, for breakfast, lunch and tea, it seems its citizens were enjoying the benefits of salt-bush-fed meat on their tables 130 years ago, even if their sheep were primarily being bred for wool. On the other end of the spectrum was Australian ‘tinned meat’ – mutton and beef ‘hermetically sealed’ in cans for the export market – a precursor to the American SPAM.

A sheep in salt bush ‘pasture’. Image source © Pastures Australia. ‘Old man salt bush’ fact sheet.

Toxic tastes

Among the various varieties of wheat, oats, barley and maize, there was also a sample of ‘arrowroot’ derived from native Burrawang, macrozamia communis or cycad palm. Most of us are familiar with arrowroot (tapioca flour) thanks to the biscuits which still endure in popularity today. Arrowroot was a pantry staple in the 19th century, considered a more delicate alternative to flour, and often used in ‘invalid cookery’ and used to thicken soups and sauces. Deemed by the judges to be ‘of excellent quality’ Mr H Moss, of Nowra received Highly Commended [6].

As with many native products, this local source of starch seems to have been largely overlooked by colonists, particularly as commercial product. The First Fleet brought with it equipment to process ‘cassada’, from which arrowroot is derived in the Pacific islands, but the settlers found no success in processing the local cycad ‘nuts’ from which Aboriginal peoples used to make ‘cakes’ or damper-like breads. Without careful and labour intensive preparation the burrawang is toxic, and the settler’s found it easier to persist with growing wheat for their bread, despite its challenges in Sydney’s soils, rather than find a local alternative.

![Burrawang (macrozamia communis) seeds. Photo by AYArktos [CC BY-SA 2.5 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.5)], via Wikimedia Commons](../../app/uploads/sites/2/2016/09/x800px-BurrawangSeeds-wiki-commons-545x409.jpg.pagespeed.ic.pPdOZs85Hm.jpg)

Burrawang (macrozamia communis) seeds. Photo by AYArktos [CC BY-SA 2.5 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.5)], via Wikimedia Commons

A French connection

The enterprising Mr Moss (who would later become mayor of Nowra) must have thought he was on to a good thing however – he had exhibited his product in the Paris Universal Exhibition in 1867 [1]. H. Moss, Shoalhaven submitted 2 samples: ‘prepared arrowroot, from the Burrawang nut’ and ‘unprepared, ditto’; Another sample of ‘macrozamia spir.’ arrowroot was also submitted by N.S.Wales Exhibition Commission, so clearly it was a resource of interest and had it received accolades, perhaps one of commercial value [6].

A product made the seeds from another native plant, ‘castanospermum Australe’ popularly known as the ‘bean tree’ for its large lumpy pods, were also exhibited in the Paris exhibition by T. Bawden from the northern New South Wales Clarence River district. According to the catalogue, ‘This starch has been highly recommended; the seeds are abundant and the manufacture inexpensive’. Cha[rle]s Moore, director of the Sydney Botanic Gardens between 1848 and 1896, went one step further, exhibiting ‘One bottle of biscuits’ made from seeds of the Bean-tree. From the description I imagine they were a bit like a Scottish oatcake or American ‘jonny cake’:

[they] are used as an article of food by the Aboriginal [peoples] who prepare them by first steeping them, in water from eight to ten days; then they are taken out, dried in the sun, roasted upon hot stones. pounded up into a coarse meal, in which state it may be kept for an indefinite period. When required for use, the meal is simply mixed with water, made into a thin cake, and baked in the usual manner. In taste, cakes prepared in this way resemble a coarse ship-biscuit. [7]

Curiously, neither the bean-tree arrowroot nor the biscuits were included in the Sydney exhibition catalogue.

Were they nuts?

While the source of the macrozamia arrowroot is understood to be the plant’s kernels, or ‘nuts’, a newspaper article published some years later, in 1910, suggest otherwise, and perhaps explains why such an enterprise was not viable, even after receiving recognition at the Australian International exhibition:

As to economic value, the farinan of the burrawang is very similar to that from the arrowroot plant in analysis and external features. But there the economic relationship ends. The [true] arrowroot is practically an annual, but how many years would it take to bring a zamia seedling to sufficient maturity to yield “a cup of arrowroot!” Probably the lifetime of an ordinary man. for it is not the nuts, but the trunk or bulb of an entire plant that yields, or did yield, arrowroot or farinae, that … Mr Moss [produced].

He told me the plant had to be broken up, and internal part treated to grinding and precipitation, as in dealing with the arrowroot bulbs.

Mr J. Maclean, ‘Burrawang Nuts’ Sydney Morning Herald, June 4, 1910 p. 6.Thumbnail images from Sydney International Exhibition Album, Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences (MAAS).

Sources and further reading:

[1] Graham Pont ‘Corroberee Interrupted’ in Colonial City Global City, Sydney’s International Exhibition, 1879. Peter Proudfoot, Roslyn Maguire and Robert Freestone, editors. Crossing Press. Sydney 2000.

[2] The Cantata commissioned for The Sydney International Exhibition for the opening ceremony of the exhibition written by Henry Kendall [part 1 (of 4)]

[3] Linda Young, Masters Thesis, ‘Let them see how like England we can be: an account of the Sydney International Exhibition 1879.’ 1983.

[4] Fielding’s guide for visitors, Sydney International Exhibition, 1879. Mitchell Library DSM/606/S

[5] Plants of New South Wales: According to the Census of Baron F. Von Mueller … With an Introductory Essay and Occasional Notes (1885). Ferdinand von Mueller, William Woolls.

[6] The official record of the Sydney International Exhibition 18789. State Library of New South Wales. DSM/606/S

[7] Catalogue of the Natural and Industrial products of New South Wales in the Paris Universal Exhibition, 1867

[8] Mr J. Maclean, ‘Burrawang Nuts’ Sydney Morning Herald, June 4, 1910 p. 6.

[9] Sydney International Exhibition Album Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences (MAAS)