In September 1879 Sydney presented itself on the world stage by hosting an ambitious International Exhibition, which ran until April 1880. The exhibition was held with typical Victorian pomp, in an expansive, purpose-built ‘Garden Palace’ located on Sydney’s foreshores, in the Botanic Gardens.

The exhibition at the Garden Palace is the focus of Jonathan Jones, winner of the 2016 Kaldor Art Prize. Kaldor’s Project 32 ‘barrangal dyara (skin and bones)‘ is a multi-faceted arts and culture project which seeks to revive the Palace in extraordinarily innovative ways, and explore its significance to Sydneysiders and to Australia’s first peoples. The ambitious project includes a series of symposia, a striking art installation which marks the location of the palace in the Botanic Gardens, free family activity days and lunchtime talks which kicked off on September 17. Yours truly will be speaking on Sunday October 2, as part of the talks series, on the ‘Food and flavours of the Garden Palace.’

Australian International Exhibition, Sydney, 1879-1880 at the Garden Palace. Image courtesy State Library of Victoria. Call # 24950

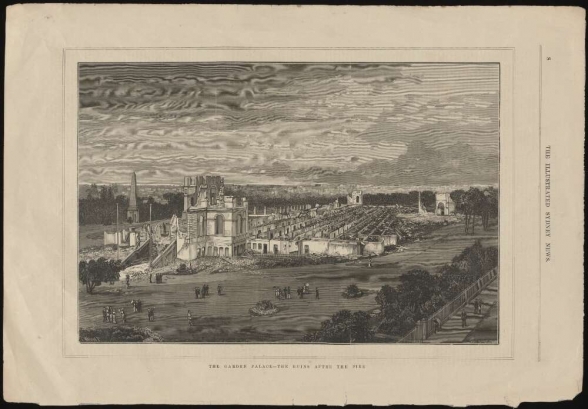

Rising from the ashes

The Garden Palace was a short-lived wonder, destroyed by fire in 1882, along with all its remaining contents, which included thousands of Aboriginal artifacts stored there by the Australian Museum. It is this insurmountable loss that is at the heart of Jonathan Jones’s concept.

The Garden Palace, the ruins after the fire. C.H. Hunt; Georgius sc. Sydney Illustrated News, 1882. Image courtesy National Library Australia. Call # S3156

A lyrical invitation

The following extract from song lyrics for the Sydney Exhibition Cantata, written to celebrate the International Exhibition, and performed at the grand opening of the Garden Palace, are something of an invitation to the world:

Lift your voices – sing for glee!

Greet the guests your fame has won,

Put your brightest garments on.

Lo, they come – the lords unknown,

Sons of Peace, from every zone!

See above our waves unfurled

All the flags of all the world!

North and South and west and east

Gather in to grace our Feast. [1]

Such was the invitation that attracted 1,045,898 visitors (more than half the population of Australia at that time), and what a feast it was! Food was vital to the exhibition’s success, if not for any other reason than providing people with the necessary staying power to cover the three floors of exhibits and surrounding pleasure grounds.

‘Fish, fowl, flesh and game … fresh and plenty’.

People were spoilt for choice – under the fountains in the centre of the Palace beneath the statue of Queen Victoria, who took pride of place under the dome, was a stylish cafe which no doubt was THE place to gather and be seen. There were also sizeable restaurants, less formal refreshment halls and an oyster saloon; ‘international’ experiences in the Vienna bakery, a Swedish cafe and a German restaurant, and plenty of treats on offer with popcorn, confectionery, and mineral water stands. [2] The New South Wales Food and Ice stand (see black & white image below) would have been very special for the many visitors who did not have the benefit of a domestic ice-chest, an appliance which was still a much desired but often expensive installation in many homes. For many visitors a picnic was the preferred mode of dining, supplemented with delicacies bought from the myriad stalls.

![The International Exhibition, Sydney, 1879-80 [picture] Gibbs, Shallard & co., Sydney : Illustrated Sydney news, January 1880. Image courtesy National Library Australia PIC Drawer 2440 #S2041](../../app/uploads/sites/2/2016/09/xnla.obj-135829716-1-auto-corrected-618x400.jpg.pagespeed.ic.zmboKKL2l0.jpg)

The International Exhibition, Sydney, 1879-80 [picture] Gibbs, Shallard & co., Sydney : Illustrated Sydney news, January 1880. Image courtesy National Library Australia PIC Drawer 2440 #S2041 [see 5 below]

A picture of sobriety?

The Temperance Movement was in full swing at this time, and played a key role in the marketing of the exhibition [3]. Along with coffee and tea, aerated drinks such as ginger ale, tonic water and lemonade and glasses of chilled fresh country milk were promoted for respectable, genteel visitors that the movement was encouraging.

For the less temperate, myriad local and European ales, wines and spirits were on offer from various vendors. Colonial wines were well represented in the exhibition, including labels we still know today from winemakers such as George Wyndham and Henry Lindeman, Penfolds, Hardy’s and Seppelt. Pale, strong and stock ales and stout could tempt the beer drinkers [4].

Refreshment stands including NSW Fresh Food & Ice Refreshment stand (centre) and the German Pavilion (right) at the Sydney International Exhibition grounds. Image source: Department of Education NSW [see 7 below].

Wining and dining

Liscensed restaurants and refreshment rooms were built by culinary entrepreneurs outside the palace, but within the surrounding grounds. Sydney caterer George Cripps’s establishment [5] could seat 600 diners, and boasted a private luncheon rooms for parties. Diners could indulge in a menu a la carte or take the cheaper table d’hote or ‘set-dinner’ option. An ornately designed refreshment pavilion run by Campagnoni & Co was, according to Fielding’s guide for visitors, ‘a very handsome building, and every possible effort is being made to make the interior arrangements conducive to the comfort of the visitors’ [2]. Its dining ‘saloon’ was 100 feet x 40 feet (33 x 12 metres), where visitors may regale themselves ‘with the choicest viands prepared by professional masters of the cuisine, and served in the most tempting and recherche style.’ [6, 3]. Emerson’s Oyster saloon and Luncheon rooms was listed in an exhibition guide offering

fish, fowl, flesh and game, of all descriptions, fresh and plenty, served up in a style to suit the most fastidious … [with] wines, beers and spirits of the very best brands [6, 3].

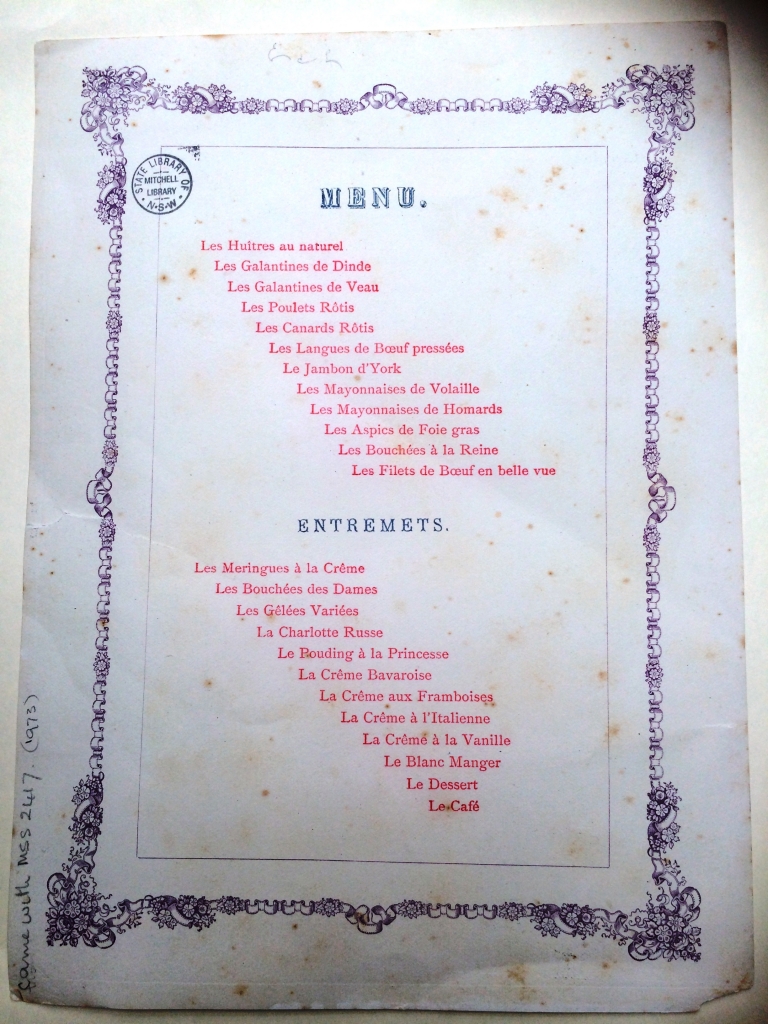

Menu from a luncheon held by the Garden Palace commissioners in 1880. State Library NSW, ephemera collection.

Menu options

Frustratingly, few menus from these restaurants survive, but the menu above, and others from the period, give an idea of the range and style of dishes served. it was customary for formal banquet menus to be presented in French, adding sophistication to the occasion, and excluding any diners who were not well educated enough in the lingua Franca to understand. On this occasion an array of cold and hot dishes were offered – oysters, turkey, veal, pressed tongue, York ham, foie gras (pate), chicken and lobster mayonnaise, roasted duck, chicken and beef and mushroom vol-au-vents. Conspicuous in its absence is lamb and mutton – clearly too ‘common’ or ‘everyday’ for such an auspicious banqueting event. The extensive list of sweets included a variety of meringues, jellies, bavarois style ‘creams’.

Australian flavour

But for the oysters, which by 1879 would have been farmed, and possibly the duck, if it were wild-caught, this menu would disappoint if you wanted to try some uniquely Australian fare. There may have been native produce at other establishments or events, as native game appears here and there on 1870s banquet menus. One banquet during held during the exhibition, at the nearby The Sydney Exchange on Macquarie Street, included a ‘haunch of kangaroo, local wild duck and ‘Bombe a l’Australienne’ [6]. What made the ‘bombe’ – a fruity ice cream dessert – characteristically ‘Australienne’ is unclear – native fruits perhaps, but most likely locally grown tropical fruits such as passionfruit and pineapple. The chef at the Sydney Exchange was obviously an enthusiast of local fare, with garfish, whiting, wild ducks and wonga wonga pigeon appearing on surviving menus from the Exchange.

Sources and further reading

[1] by Henry Kendall [part 1 (of 4)]

[2] Fielding’s guide for visitors, Sydney International Exhibition, 1879. Mitchell Library DSM/606/S

[3] Diana Noyce ‘How like England we can be: Feeding and accommodating visitors to the international exhibitions in the British colonies of Australia in the nineteenth century’ in A taste of progress: Food at international and world exhibitions in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Nelleke Teughels and Peter Scholliers (eds). Routledge 2016.

[4] The official record of the Sydney International Exhibition 18789. State Library of New South Wales. DSM/606/S

[5] Cripp’s pavilion is the small building to the right of the arched street entry-way marked building #2 on the colour picture above; Compagnoni & Co (#8) is behind the cluster of terraces in the foreground, after the bend in the road. You can zoom into the picture on the NLA catalogue for closer detail: http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-135829716/view

[6] Graham Pont ‘Corroberee Interrupted’ in Colonial City Global City, Sydney’s International Exhibition, 1879. Peter Proudfoot, Roslyn Maguire and Robert Freestone, editors. Crossing Press. Sydney 2000.

[7] NSW Department of Education 1879 International Exhibition resources including featured image.