Returning to our colonial spice-box this week, we’re indulging in nutmeg and its lesser known botanical companion, mace. Mace was equally, if not more prevalent in the 18th and 19th century recipes.

Nutmeg

Nutmeg is, historically, steeped in mystery and exoticism – often purported to have aphrodisiac qualities, its heady fragrance sending people swooning. It is also renowned as having hallucinogenic responses if taken in great quantity, and some suggest it can be addictive. Mrs Beeton cautioned her readers in 1861: ‘it ought to be used with caution by those who are of paralytic or apoplectic habits’ – consumer beware!

In culinary use, nutmeg is one of those less is more spices, and really shows its qualities when freshly grated, as once it is ground it can lose its delicate velevety top notes and develop a harsh menthol-like taste. Nutmeg graters were standard kit in colonial kitchens, many of them cleverly designed to fit inside spice caddies and palletes, or purchased as single gadgets, often with a built-in space to store the nutmegs. On the classic but cumbersome box grater, the very small spiky side that were never sure what to do with, which is intended for nutmeg. As nutmegs themselves are generally small, it is almost typical that one will grate their fingers as well, so various ‘contact free’ devices have been produced, including the handled whistle-like contraption shown below.

Nutmeg graters from the Caroline Simpson Library and Research collection. Photo © Jamie North for Sydney Living Museums

A private stash

In the 18th century, one might carry a pocket-sized grater on their person, much like some might carry snuff, so that a scraping of nutmeg could always be at the ready to grate into a hot toddy, a brandy or rum based milk drink much admired in Georgian times. Thomas Mackenzie (1794-1892), grandfather of the Thorburn sisters who lived at Meroogal, was one of these individuals, remembered as being rather fond of a hot toddy. His personal nutmeg grater (shown below) was designed with a double-hinge – the lid opening to access the grating plate, which was set deeply enough inside the box to allow a whole nutmeg to sit under the lid; the base could then be released to allow the fresh gratings to be sprinkled onto the toddy.

Buttered Toddy. – Mix a glass of rum-grog pretty strong and hot, sweeten to taste with honey, flavour with nutmeg and lemon-juice, add a piece of fresh butter about the size of half a walnut.

Edward Abbott, The English and Australian cookery book, for the many, as well as “the Upper ten thousand” (1864)

Thomas Mackenzie’s silver nutmeg grater. 27 x 60 x 34 mm. Maker unknown. England, mid-1800s Photo © Sydney Living Museums. Note the double hinging to release the lid and the base.

Similarly, the pocket grater shown below is about the size of a man’s thumb, from the top knuckle. The nutmeg itself can be stored inside, accessed by unscrewing the the base-plate of the grater. As pocket graters go, it is very plain; some are far more ornate, some made from silver, bone, shell, hand-carved wood; rarer than snuff boxes, they are highly collectible.

Personal Georgian nutmeg grater by Samuel Pemberton, private collection. Photo Alysha Buss © Sydney Living Museums

Mace

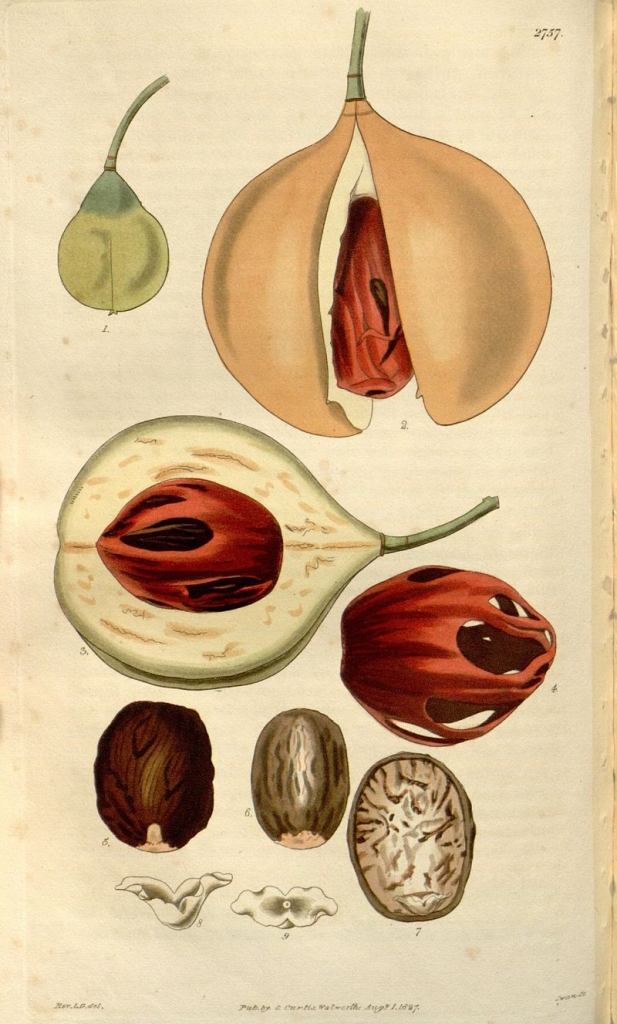

Mace is found within the same fruit that yields the nutmeg seed, and recipes from the early 1800s suggest that mace was used more prevalently in cooking than the nutmeg itself. But first up, let’s clarify : culinary mace is not to be confused with the ‘mace spray’ which is used as a personal defense weapon; it is more correctly but equally confusingly termed ‘pepper spray’ as its active ingredient is capsicum or chilli based (see our previous cayenne and ‘Indian’ pepper story). Culinary mace is the brick-red aril that encloses the seed of the fruit that contains the nutmeg itself; or in Mrs Beeton’s description:

this is the membrane which surrounds the shell of the nutmeg. Its general qualities are the same as those of nutmeg, producing an agreeable aromatic odour, with a hot and acrid taste. If is of an oleaginous nature, is yellowing in its hue, and is used largely as a condiment.

Nutmeg fruit, seed and aril. Photo: slashme under wiki commons license, 2016

Blade mace

Being part of the nutmeg plant, mace has a pleasant nutmeggy aroma with a light lemony topnote; when ground it is not quite as bold as ground nutmeg, which can have a strong ‘menthol’ like flavour once it stored for any length of time, and used too liberally. The vibrant red colour of the aril fades as it dries, to an amber-orange. The resulting spice is called blade mace, or singularly, a blade of mace. Whole blades of mace are useful for making milk puddings, white sauces and savoury custards, as the blades can be strained out once its flavour has been infused in slow cooking, leaving a speckle-free end product. We tend not to be so fussy about this now, but purity was once an important factor in creating dishes for royalty or high status diners. Mace is a key ingredient in bread sauce, traditionally served with roast chicken and fowl, in savoury custards and creamy potato dishes, delicate white sauces for fish, seafood and potted meats, especially for whiter meats, such as chicken and veal and potted prawns. Mace was also used in sweet dishes such as cheesecakes, puddings and baked goods, in its own right or along with nutmeg.

Kissing cousins

Nutmeg has a higher yield than mace, and as it has similar characteristics in flavour (though I argue, noticeable differences) nutmeg has come to dominate the retail market. As a consequence, recipes have been rewritten to use nutmeg instead, leaving mace as a largely forgotten ingredient. Mace can be found in specialty spice merchants and Indian grocers’ shops.

Myristica Officinalis Aromatic, or True Nutmeg Tree in ‘Curtis’s Botanical Magazine or Flower Garden Displayed’ 1827. Image via wikicommons.

Power and politics, again

These two spices, over which much blood was spilled in the 18th century, to control their supply from the Molluccas, or Spice Islands of the Indonesian archipelago, are actually from the same plant, nestled within the fruit of the Myristica Officinalis, or nutmeg tree. In a history according to Mrs Beeton (1861) the nutmeg tree is:

‘a native of the Moluccas and was long kept from being spread to other places by the monopolizing spirit of the Dutch, who endeavoured to keep it wholly to themselves, by eradicating it from every other island… [but] through the enterprise of the British, has now found its way [elsewhere] where it flourishes and produces well.

Isabella Beeton, Book of household management (1861)

Bless Mrs Beeton for her patriotism, but it was a Frenchman, Pierre Poivre, the original Peter Piper of pickled pepper fame, and his band of international smugglers who broke the Dutch monopoly, transplanting seedlings of nutmeg trees in French Reunion and Mauritius.