Now that you’re assembling your summer salads you’ll of course be looking for decorative bottles in which to keep your vinegars. Pass the cruet!

Even a quick flick through a historic recipe book such as Mrs Beeton or Cassell’s will show you how many sauces and flavoured vinegars were in use: anchovy sauce, mushroom and walnut ketchup, ‘Epicurean’ sauce, lemon pickle, green mint vinegar, horseradish vinegar, elderberry ketchup – and of course soy sauces and Worcestershire sauce. Their place on the table reflect the matching of particular sauces to dishes, but also household favourites – and the time of day. But what to put them in…

Cruet sets

While they are not as standard on domestic tables as they once were, cruet bottles and sets are actually quite common today, and made in everything from silver, crystal and glass to everyday plastic. When you reach for the sugar at your cafe, or the vinegars and soy at yum cha it may be kept in a small cruet stand.

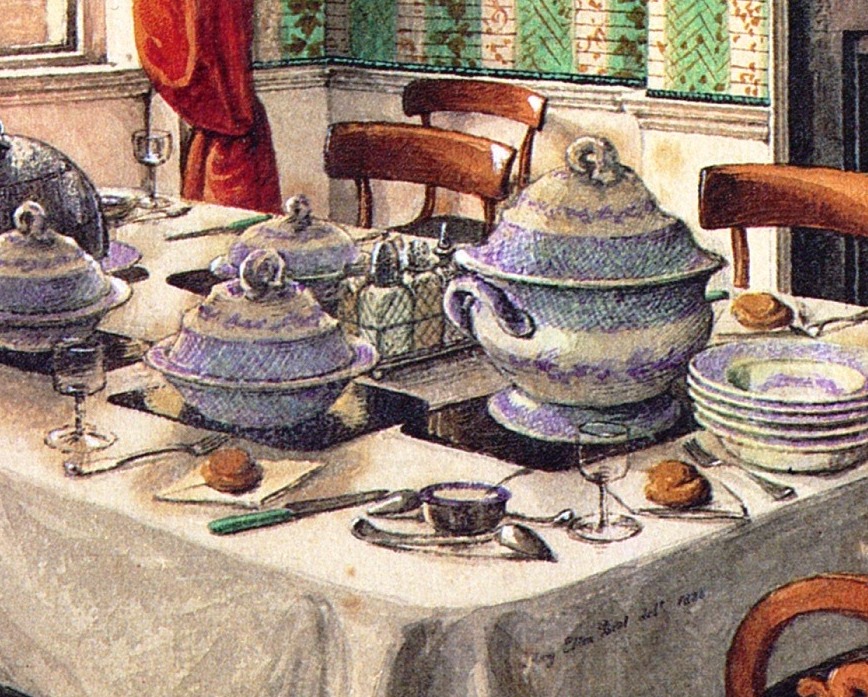

This well-known view by Mary Ellen Best of a table setting at her house at York includes a cruet set of 6 individual, square profile bottles just behind the soup tureen. Identifiable are an oil bottle with its pourer, and a sugar or pepper caster (salt cellars are placed on the table corners) and 4 other bottles for liquids.

Mary Ellen Best, ‘Our dining table at York’. From Caroline Davidson “The world of Mary Ellen Best” (1985)

While the entire set is now often called a ‘cruet’ – and the name is often applied to other portable table items such as ‘egg cruets‘ – strictly speaking the term refers to the individual, usually slim bottles; the stand itself is called a ‘cruet frame’.

Dr Johnson in his 1755 Dictionary defined a cruet as “A vial for vinegar or oyl, with a stopple.” ‘Stopple’ being the most marvellous word. More precisely, a cruet is a small, thin bottle with a flat base and stopper. They’ve existed for millenia – a small ancient Greek ‘lekythos’ for holding oil for table use could easily be called a cruet. As with liqueur bottles and decanters, small labels could be hung around the neck or even inscribed on the cruet to inform the contents.

Dated 1800 by its hallmark, this example from Elizabeth Bay House is completely typical of the period. You can clearly see the 4 thin ‘cruets’:

Silver plate oval cruet set by Crispin Fuller, 1800, from the Elizabeth Bay House Collection. Photo © Nicholas Watt for Sydney Living Museums

Originally the stand also held two larger ‘ewer-shaped’ (handled like a jug) bottles to the sides that contained oil and vinegar. The larger vessels with the pierced tops are casters, for sugar or pepper.

Cafe cruet sets contain everything from vinegars and oils, to sauces, sugar, salt and pepper and serviettes. This is a basic set I used on the weekend; now it just has salt and pepper, but it originally had a vinegar bottle and sugar caster where the ‘sugar bowl’ for sachets now sits. The shakers aren’t original either, all four were probably square. Still, you get the idea :

Depending on the household the contents of everyday domestic table cruet sets range from soy, fish sauce and sweet or fiery chilli oils to the extra virgin olive oil and balsamic vinegar. It was this classic pair – the oil and vinegar set – that arrived from Italy to Britain in the early 1600s, and began to develop into the more expansive ‘cruet set’. By the late Georgian period it developed to include casters for sugar and pepper, and mustard jars – and soy bottles for different imported sauces from the Far East.

This example of a cruet frame is from Rouse Hill – missing its individual bottles:

Cruet stand for 7 individual bottles, from the Rouse Hill House and Farm Collection. Photo © Sydney Living Museums R80/13

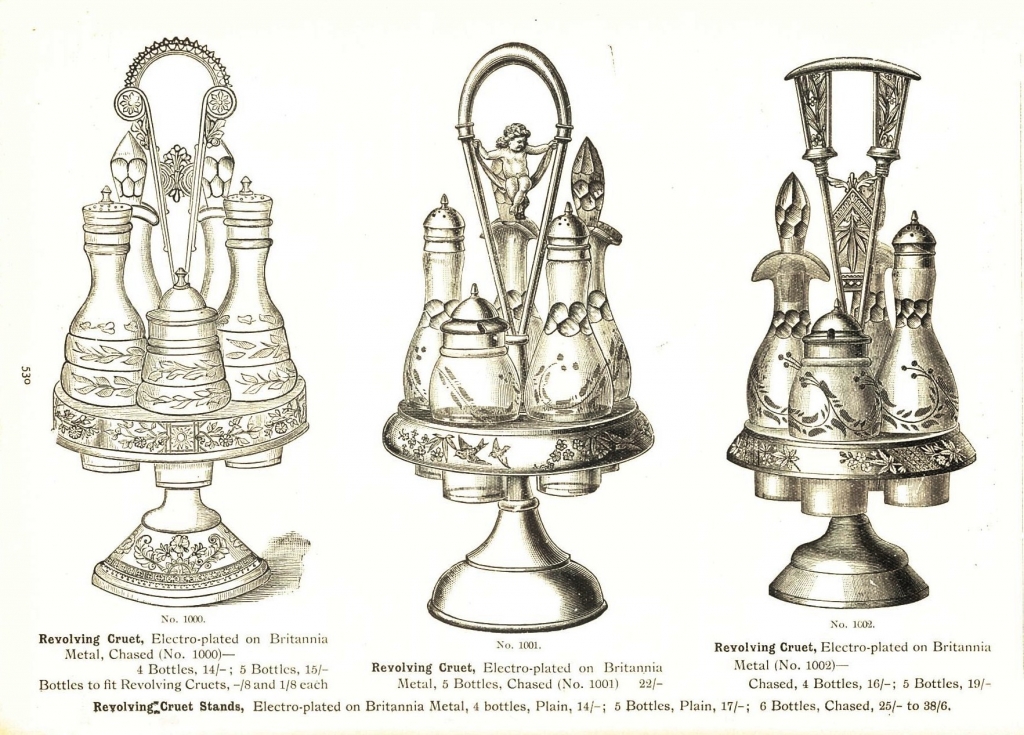

You can see how it once held its bottles – 5 large and 2 smaller – by the similar examples in this Anthony Hordern catalogue from 1914. You can see from their tops that some are for oils, sauces or vinegars, others for mustard (the shorter bottles that have a spoon slot in their caps), and salt and pepper (the single shaker in the right-most example is just for pepper) shakers:

Revolving cruet sets advertised in Anthony Hordern and Sons’ household catalogue, Anthony Hordern & Sons, Sydney, July 1914, page 530

Breakfast, lunch and dinner

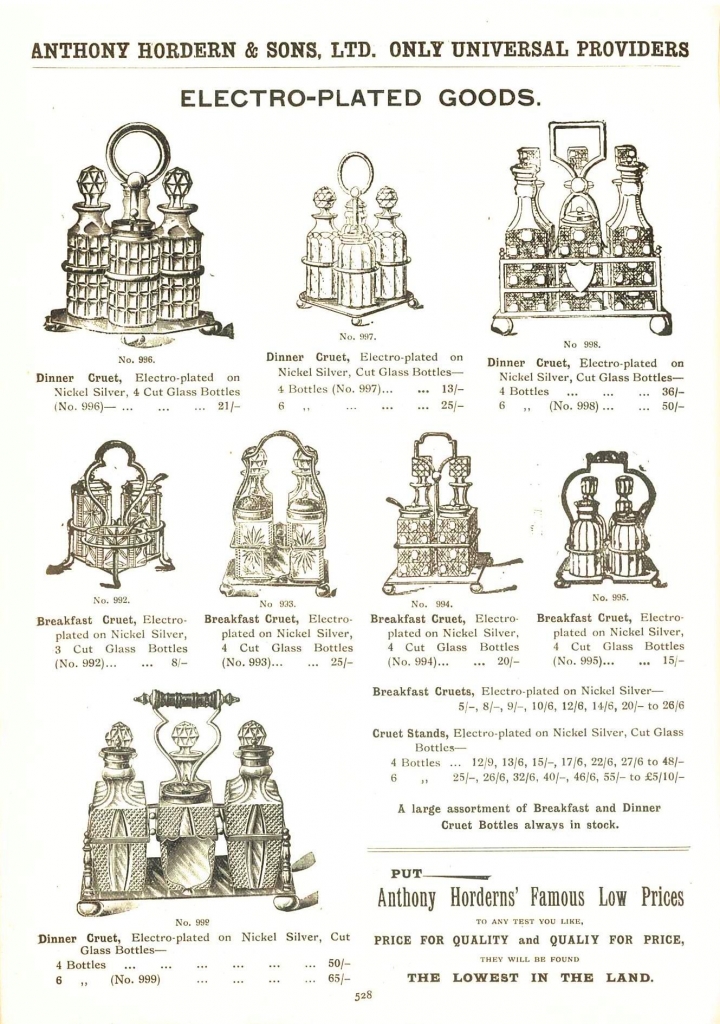

If you look at this page you’ll see that there are a range not just in expense and size, but in intended use: breakfast, lunch and dinner cruets.

Cruet stands advertised in Anthony Hordern and Sons’ household catalogue, Anthony Hordern & Sons, Sydney, July 1914, page 528

This cruet set with a loop handle on the back rather like a chamber-stick and small hoof feet is also from Rouse Hill. The lidded bottles are for mustard, pepper and sugar – the salt being placed in the built-in dish rather than a separate salt cellar. Its rather small size – the bottles are only 4cms high – suggests an individual place, such as a breakfast tray, rather than being passed around a table. (The rather natty apostle spoon with the head in the shape of a clam shell is not part of the set):

Small 3 bottle breakfast cruet set incorporating a salt cellar, from the Rouse Hill House and Farm Collection. Photo © Sydney Living Museums R87/148-1:4

…while this small tripod-shaped cruet, also for individual use, is more likely for lunch as it contains two mustard pots and a cruet bottle for a vinegar. Dishes that suited vinegars and oils were more likely for lunch and dinner, especially if they included salads that were often dressed at the table so they were as fresh as possible.

Individual tripod-framed cruet for 2 mustard jars and a vinegar bottle, from the Rouse Hill House and Farm Collection. Photo © Sydney Living Museums R87/149-1:5

While for breakfast and luncheon (that new fad!) the cruet was to be set on the table, at dinner James Williams (The Footman’s Guide, page 54) placed the cruet set on the sideboard, from where it was carried around as needed. He gave directions for their maintenance:

[T]he cruets must be looked to every day, wiped and dusted, the mustardspoon, or any other used with the stand, being always in its proper glass, and clean. The mustard, vinegar, &c. should be put into the cruets in good time before wanted for the table, but not suffered to remain too long therein, or they will stain and discolour the cruet. The insides of the cruets will require a thorough washing about once a month, the same way as directed for decanters, taking care to clean the oil cruet last.

Given the residue that vinegars and sauces leave, I’d be advocating cleaning them every few days at most – along with your decanters!

“Store sauces”

Flavoured vinegars are exceptionally easy to make – and not forgetting that you can re-use the vinegar from your pickles. These recipes from Acton and Beeton are for flavored vinegars for use in making salad dressings. They’re what are called ‘store sauces’, meaning they’re for suitable for making and storing for later use – rather than being ‘store-bought’. The best advice Jacqui and I can give is to always use a good quality vinegar as your base.

Tarragon Vinegar [from Eliza Acton – how very 1980s!]

Gather the tarragon just before it blossoms… strip it from the larger stalks and put it into small stone jars or wide necked bottles and in doing this twist some of the branches so as to bruise the leaves…; then pour in sufficient distilled or very pale vinegar to cover the tarragon; let it infuse for two months, or more; it will take no harm even by standing all the winter. When it is poured off, strain it very clear, put it into small dry bottles, and cork them well. Sweet basil vinegar is made in exactly the same way, but it should not be left on the leaves more than three weeks. The jars or bottles should be filled to the neck with the tarragon and before the vinegar is added: its flavour is strong and peculiar, but to many tastes very agreeable. It imparts a foreign character to the dishes for which it is used.Celery vinegar [from Mrs Beeton]

Ingredients – 1/4 oz of celery-seed, 1 pint of vinegar

Mode – crush the seed by pounding it in a mortar ; boil the vinegar, and when cold pour it to the seed; let it infuse for a fortnight, when strain and bottle off for use. this is frequently used in salads.Cucumber vinegar (a very nice addition to salads)

Ingredients:- 10 large cucumbers, or 12 smaller ones, 1 quart of vinegar, 2 onions, 2 shallots, 1 tablespoonful of salt, 2 tablespoonsful of pepper, 1/4 teaspoonful of cayenne.Mode:- pare and slice the cucumbers, put them in a stone jar or wide mouth bottle, with the vinegar. Slice the onions and shallots and add them, with all the other ingredients, to the cucumbers. Let it stand 4 or 5 days, boil it all up, and when cold, strain the liquor through a piece of muslin, and store it away in small bottles well sealed. This vinegar is a very nive addition to gravies, hashes, &c., as well as a great improvement to salads, or to eat with cold meat. [1]

For a complete twist why not try a raspberry vinegar cordial!

Sources

Eliza Acton, Modern cookery for private families, 1845

Beetons Book of Household Management, 1861

Caroline Davidson, The World of Mary Ellen Best, Chatto & Windus, 1985