Since we’re talking spices, this week we’re taking a seat at the table and having a seasoned look at the salt and pepper shakers – before we tuck into a delicious toast sandwich. Seriously!

There are so many salt and pepper-themed sayings in everyday use that we can easily forget that spices such as pepper, imported along the spice routes by a succession of traders, were once fabulously expensive. There’s ‘salting the accounts’, ‘worth his salt’, ‘to sit below the salt’, a ‘peppercorn rent’ and on it goes. Historically salt cellars could be astonishing creations that reflected the worth of their contents as much as the stature of their owners – just have a look at the dazzling ‘Cellini cellar’ by the Florentine silversmith Benvenuto Cellini for Francis the first of France! Its a far cry from the little paper sachets of salt and pepper that come with takeaway food today.

Salt and pepper shakers and condiment holders, though their actual contents may be extremely inexpensive today, can of course be wonderful things. This cruet set, sadly missing its pair of oil ewers that sat one at each end, is hallmarked for the London silversmith Crispin Fuller (d.1824) and the year 1800. It has small bottles for oils, vinegars and soy, all with stoppers, and two larger, bulbous casters. You can usually see it as part of the breakfast room setting at Elizabeth Bay House:

Cruet set. Elizabeth Bay House Collection, Sydney Living Museums. Photograph © Nicholas Watt

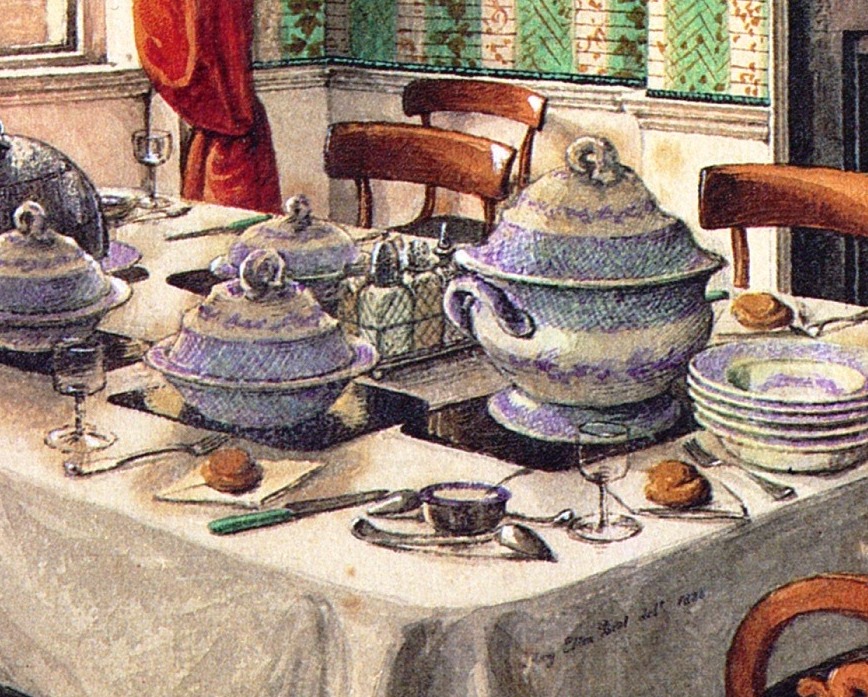

But what were the casters for? If you look closely you’ll see that the hole sizes and patterns in the tops aren’t the same, which tells us that they were for ‘casting’ two different powders, one with a coarse grain (to the right side of the cruet) and one very fine (to the left). The obvious guess would be for salt and pepper respectively, but its also possible that while one was for pepper the other was for sugar (sugar casters are somtimes called ‘dredgers’); salt would then have been served quite separately in two or more cellars, possibly made to match the cruet with its anthemion-decorated feet. You can see salt cellars on the table corners in this detail of a painting by Mary Ellen Best:

Mary Ellen Best; detail of ‘Our dining table at York’.

Just to complicate matters, the pepper was possibly not black pepper at all, but could also be the more fiery cayenne pepper – though this would be more likely if there were two casters with the same, small-sized holes. If you look at the two casters in the image at the top of this post, you can see their hole sizes and pattern are also different; they are hallmarked for 1757, and given their date are quite possibly for pepper and cayenne. Larger cruet sets could include a caster for mustard seed powder as well, which could then be mixed with vinegars to taste on the diner’s plate. Later, it was common to include a pot for ready-prepared ‘wet’ mustard. These typically have a glass insert and a hinged lid and spoon. ‘ Breakfast sets’, often quite small so they sat on a tray, often consist of salt and pepper shakers with a small mustard pot.

Pass the salt

The catch with using silver is that it reacts very badly with salt. If you look a this round, three-legged ‘cauldron’ cellar from the Museum of Sydney collection – part of a 24-piece collection of silver cutlery provenanced to the family of Governor Bourke and bearing the Bourke crest – you’ll notice a faint yellow-gold tinge:

Salt cellar provenanced to the family of Governor Richard Burke in the Museum of Sydney Collection. Photo (c) Sydney Living Museums

This is a coating of non-reactive gold, that separates the salt from the silver, just like the tin lining of a copper pot. A cardinal rule is never, never, never scrub away at the interior if you’re cleaning a cellar. You can remove the gilding and then you’re in trouble! In this image there are two distinctive ‘boat-shaped’ salt cellars, hallmarked to Henry Sandit and circa 1797-98, that have almost lost their coating after two centuries of polishing:

Georgian boat-shaped salt cellars and pepper caster. Elizabeth Bay House Collection, Sydney Living Museums. Photograph © Nicholas Watt

Because salt is corrosive (as anyone who parks near the ocean will tell you) salt cellars are commonly made of glass, crystal or ceramic or have a glass insert (they often make rather stylish re-purposed tea-candle holders). Note that they come in pairs in this Anthony Hordern & Sons catalogue, one for each end of the table:

Selection of salt cellars available from Anthony Hordern & Sons in their July 1914 catalogue, p1409. Courtesy Gary Crockett

More ample settings could have more, even a cellar per diner.

Also called a ‘salt kit’, a ‘salt pig’ is very different: larger, and kept in the kitchen for use while cooking. The common design is open-mouthed, looking very much like a section of bent piping, so you grab a pinch with your fingers rather than use a spoon. The design supposedly stops the salt from clumping as it absorbs moisture from the air.

Pass the pepper

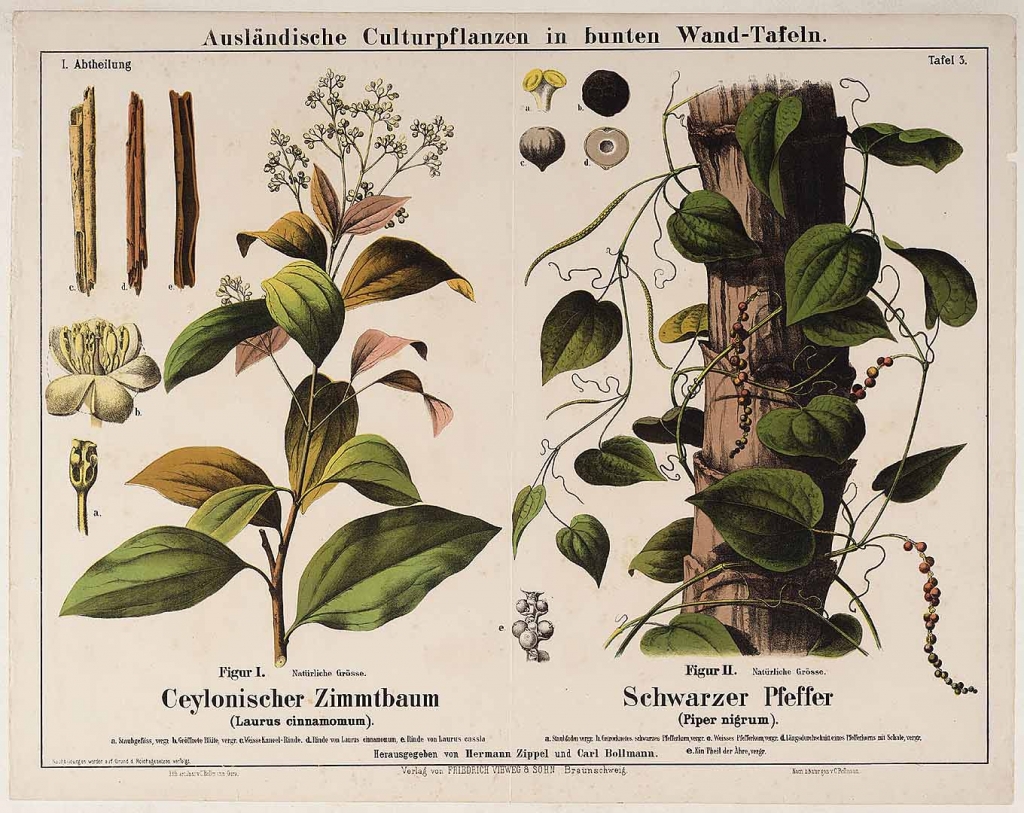

- Botanical wallchart showing the cinnamon tree and pepper vine; Hermann Zippel & Carl-Bollmann, ‘Auslandische Culturpflanzen in bunten Wand-Tafeln’.1876. Image courtesy of the Missouri Botanical Gardens

The pepper plant is a vine, that produces tendrils of small berries. For centuries it was pepper that produced the characteristic heat in dishes from Europe right across to South-East Asia; with the introduction of chilli from central America there was revolution in cooking, and you almost can’t think of Thai or Szechuan cooking without chilli. In Cambodia however pepper still reigns supreme, and the Cambodians are proud of the Kampot pepper grown in the south of the country, and which is seeing a great resurgence in recent years. For the diners at Elizabeth Farm and Elizabeth Bay House pepper was imported into New South Wales; while salt, which apart from its place on the table was used in vast quantities in food preservation, was also imported it was produced locally by boiling down sea water. For many years salt boilers could be seen busy at work around the harbor, stoking fires under cauldrons and trypots – it was a horrible job.

Feeling frugal?

Why not do away with everything but the seasoning! Back in November, 2011 the British press [1] was briefly obsessed with what was dubbed ‘the worlds cheapest lunch’ : an actual recipe from Mrs Beeton for a sandwich of buttered bread with a filling of and toast, salt and pepper!

TOAST SANDWICHES.

Ingredients. — Thin cold toast, thin slices of bread-and-butter, pepper and salt to taste. Mode. — Place a very thin piece of cold toast between 2 slices of thin bread-and-butter in the form of a sandwich, adding a seasoning of pepper and salt. This sandwich may be varied by adding a little pulled meat, or very fine slices of cold meat, to the toast, and in any of these forms will be found very tempting to the appetite of an invalid.

Presumably the interest is in the quality of the bread and butter, and the contrast in texture between that and the thin toast. Mmm delicious… I’ll pass thanks.

Notes

1. see for example this BBC report http://www.bbc.com/news/uk-15752918

I’ve talked about cruet sets a while back, you can read that post here.

Read more about mustard casters in a blog post by Patricia Reber here.