‘The inhabitants of a beer-drinking or spirit drinking country will never possess the vivacity of those who live in a wine producing land’ Phillip Muskett, 1893

Visiting Orange during Wine Week encouraged me to reflect further on colonial wine culture. The Australian wine industry started with the first fleet, which arrived with grape vine cuttings in 1788.

The fleet picked up samples on the voyage as they stopped in at Tenerife, Rio De Janeiro, and the Cape of Good Hope. Few survived but those that did were planted in the governors garden:

In the Governor’s garden… the orange trees flourish, and the fig trees and vines are improving still more rapidly. In a climate so favourable, the cultivation of the vine may doubtless be carried to any degree of perfection; and should not other articles of commerce divert the attention of the settlers from this point, the wines of New South Wales may, perhaps, hereafter be sought with avidity, and become an indispensable part of the luxury of European tables.

The Voyage of Governor Phillip to Botany Bay, 1789.

A gentlemanly pursuit

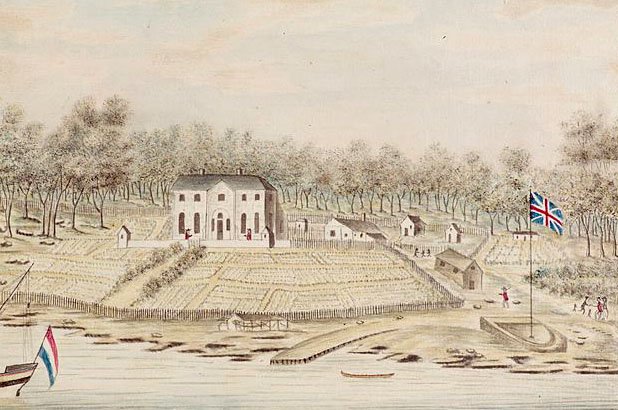

As discussed previously in this blog, wine grape growing was a gentlemanly pursuit, with vineyards planted on most colonial estates, including those of Dr Redfern in Sydney, Gregory Blaxland at Eastwood, Samuel Marsden at Ryde, John MacArthur at Parramatta and later at Camden. By the 1830s new territories were opening up in the Illawarra, Hunter Valley and beyond the Blue Mountains at Bathurst and viticulture naturally accompanied settlement. Few British immigrants had experience in wine making, and there was much experimentation with grape varieties and wine production methods and it took several decades for what might be termed a ‘wine industry’ to be established. Some well known contemporary wine labels have their roots in the nineteenth century, including Lindeman’s, Angove’s family wines and Wyndham Estate.

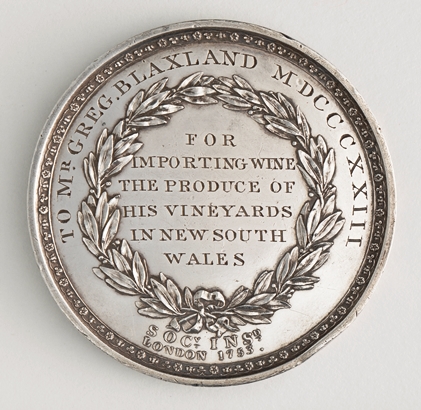

Medal awarded to Gregory Blaxland for wine export from New South Wales, 1823, verso. State Library of NSW R 266

Colonial wines

Local wines competed with global imports, but gradually gained favour, here and overseas where they were entered in various international exhibitions and wine shows. It was noted though, that ‘a wealthy man will never give you colonial wine, not because it is worse than the imported stuff on their tables, but [simply] because it is colonial’. The Australian cultural cringe was clearly not a twentieth century phenomenon.

Medal awarded to Gregory Blaxland for wine export from New South Wales, 1823. State Library of NSW R 266

Trial, error and courage

Transcripts of George Wyndham’s diaries held in the Mitchell Library make compelling reading, detailing the day-to-day efforts experienced to build a modest home for a growing family and the harsh realities of living in a remote area, more than a days walk away from the nearest township or medical care. They detail the trials and errors, small successes and major losses in agricultural efforts, difficulties negotiating convict workers, bush-rangers, friendly and hostile Aboriginal groups, and dealing with climate extremes and destructive storms and floods. These, and other settlers’ stories demonstrate the courage, determination and tenacity required to carve out a life on the land in colonial New South Wales, let alone build commercial empires from their efforts and vision.

Grape picking at Dalwood Vineyards, Branxton 1886 from Photographs of the Dalwood Vineyards near Branxton, New South Wales, Australia, 1886. State Library of NSW PXD 740/9

A quest for virtue and good grace

Since first settlement, spirits and to a lesser extent ales (which were more potent than today’s commercial brews) were the drinks of choice for most colonists. Tea was a great comfort, but colonial life was hard for many early settlers and labourers, and alcohol an attractive and accessible relief for some. But their crudeness and high alcohol content affected the health and wealth of many who succumbed to its charms. Wine on the other hand was regarded ‘a wholesome and innocent beverage that produced virtue and good grace in its drinkers, whereas spirits were the source of ruination and disgrace.’ (Griffin, 1992). Never mind that the wines on most tables were fortified – sherry, port, or table wines fortified with brandy, which improved keeping quality and helped disguise any roughness from poor production processes, so definitely packed a punch.

In the government’s eyes, alcoholism was detrimental to the development of the colony, economically, socially and morally. But let’s not forget another reason for the government’s active endorsements for wine drinking: politicians themselves and those in their circles – lawyers, magistrates, doctors were generally those who produced wine grapes on their estates and needed to develop a local market. And large landholders, generally free settlers or the gentle classes, had much to gain from a sober working force, particularly as convict transportation ceased in the mid century and labour costs increased.

Respected physician Phillip Muskett criticised Australian wines in his treatise ‘The art of living in Australia (1893), for their high alcohol content (18 – 20% by volume), advocating lighter wine styles such as those produced in southern Italy and Spain. He stated, ‘it is vastly more important to have good ordinary, alimentary wine of fine cepage (style) not beyond 10% of spirit or even 6%.’ Muskett was not the first to call for moderation. One of our best known ‘wine doctors’ Henry Lindeman wrote in 1871,

I have spent many years of my life trying … to inculcate a taste for a pure, dry and thoroughly fermented wine, free from excess undecomposed sugar and light in alcohol resembling Bordeaux and Rheingan…

It’s taken over a hundred years to heed their advice, but there is now a reasonable selection of low alcohol wines on the market.

References and further reading

Robert Griffin, ‘The worship of Bacchus: wine in colonial New South Wales’ Historic Houses Trust, 1992

Julie McIntyre. First Vintage: wine in colonial New South Wales. UNSW Press (2012)

Richard Twopenny. Town life in Australia. (1883).

Phillip Muskett, The art of living in Australia (1893)

The Cook and the Curator, A gentleman’s cellar.