Though it seems the weather in Sydney is never going to cool down, its time to look at apples: from apple Charlotte cake to chutney, and a baked apple recipe that kids will love to try for mothers day. But first its cider time!

Cider: i. all kinds of string liquors except wine; this sense now wholly obsolete

ii. Liquor made of the juice of fruits, pressed.

iii. The juice of apples, expressed and fermentedSamuel Johnson, 1755

Cider may seem to be the drink of choice right now (which is great news to our fruit growers), but it has a long, long history.

In the early days of the colony it wasn’t apples that were used to produce cider, but peaches. You may remember the peach braggot made for the Eat Your History exhibition. In 1819 William Charles Wentworth (of Vaucluse House) wrote: ‘Of all the fruits which I have thus enumerated as being produced in this colony, the peach is the most abundant and the most useful… Cider also is made in great quantities from this fruit, and when of sufficient age, affords a very pleasant and wholesome beverage.’ Apples – and apple cider – he noted took longer to become established, though he was in no doubt they would thrive ‘over the mountains’ as they had in Van Dieman’s Land, or, as it is better known, Tasmania:

The climate, however, of Port Jackson, is not altogether congenial to the growth of the apple, currant, and gooseberry; although the whole of these fruits are produced there, and the apple, in particular, in very great abundance; but it is decidedly inferior in quality to the apple, of this country. These fruits, however, arrive at the greatest perfection in every part of Van Diemen’s Land; and as the climate of the country to the westward of the Blue Mountains, is equally cold, they will without doubt attain there an equal degree of perfection; but the short period which has elapsed since the establishment of a settlement beyond these mountains, has not allowed the nltramontanians [1] to make the experiment. [2]

Making cider was a skill that many settlers from rural Britain brought with them, though a lack of equipment required some local resourcefulness:

We are happy to learn that some successful experiments have been this year made in expressing cyder from the peach, in such quantities as to promise real advantage. Several of the settlers at Kissing Point have devoted much attention to the praise-worthy object; one of whom informs us, that he has already put up about 200 gallons; which with a few months fermentation, he doubts not will be found equal to the apple-cyder in strength, and not inferiorto the taste. To effect this, however, his labour has been prodigious, owing to the mode in which, for want of a press, he was obliged to extract the juice.

To this end he had recourse to every inventive faculty; and first, to separate the fruit from the kernel, hewed the butt of a tree out in shape of a mortar, wherein he readily accomplished this part of the task; then smoothing off the flat side of another tree, which, he designed using as a part of the press, prepared a substantial board as its opposite ; and against this raising the best purchase he could, a tolerable portion of the juice was extracted, which ran into vessels set purposely to receive it. He had the last year commenced the operation, but merely by way of experiment, and upon a very small scale ; the produce of which, bottled off, attained to so much excellence in the course of six or seven months, as to determine him to extend his plan.The Sydney Gazette, March 3rd, 1805

Last year I had a trip through to Tasmania and at Woolmers, a house similar in many ways to our own Rouse Hill House, saw a surviving 19th century cider mill.

First, pick your apples…

Woolmers, Tasmania_Photo (c) Scott Hill

Together with its neighbour, Brickenden, Woolmers in Northern Tasmania is one of the 12 World Heritage-listed Convict Sites – along with our own Hyde Park Barrack. A building for a ‘cider press’ is listed at Woolmers in the 1840s [3], though estate signage today dates the extant cider mill-house, located adjacent to the large wool-shed in the outbuildings precinct, to the 1860s. The mill itself has been repaired / restored twice, most recently in 2001. You can clearly see the new blocks:

Apple mill at Woolmers showing the trough and roller. Photo (c) Scott Hill

In this photograph you can also see how the central blocks are clamped together, not a single massive stone:

Detail of Woomers apple mill showing clamped stone construction. Photo (c) Scott Hill

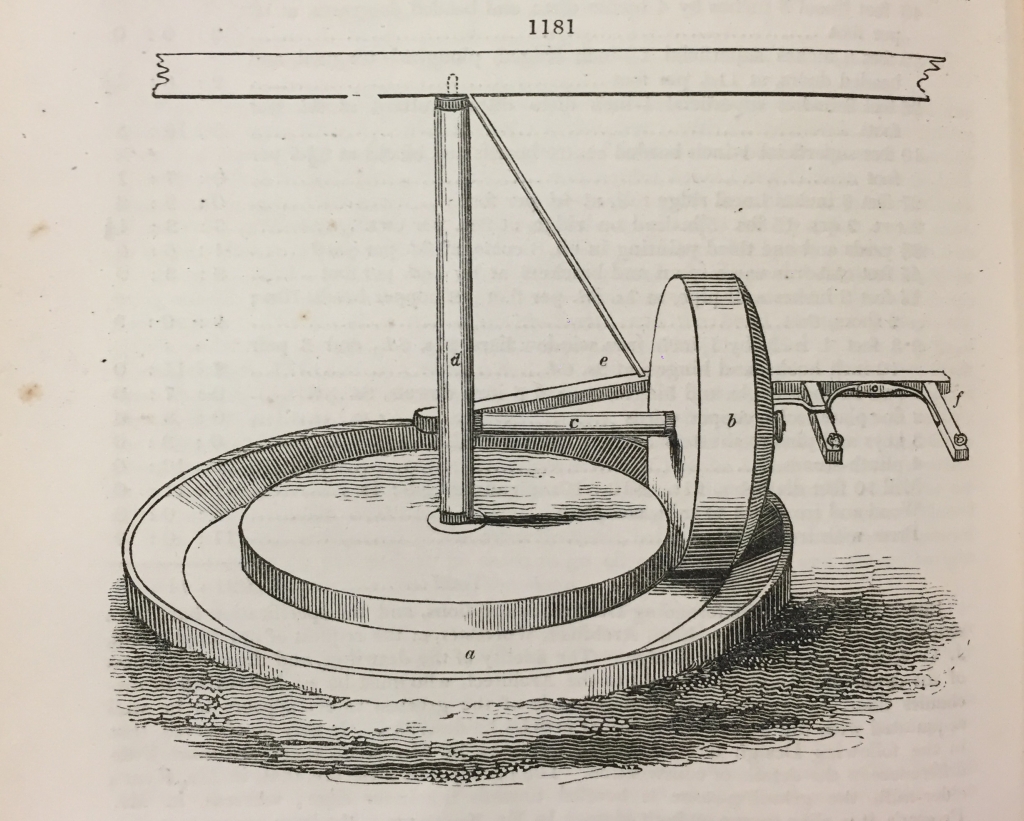

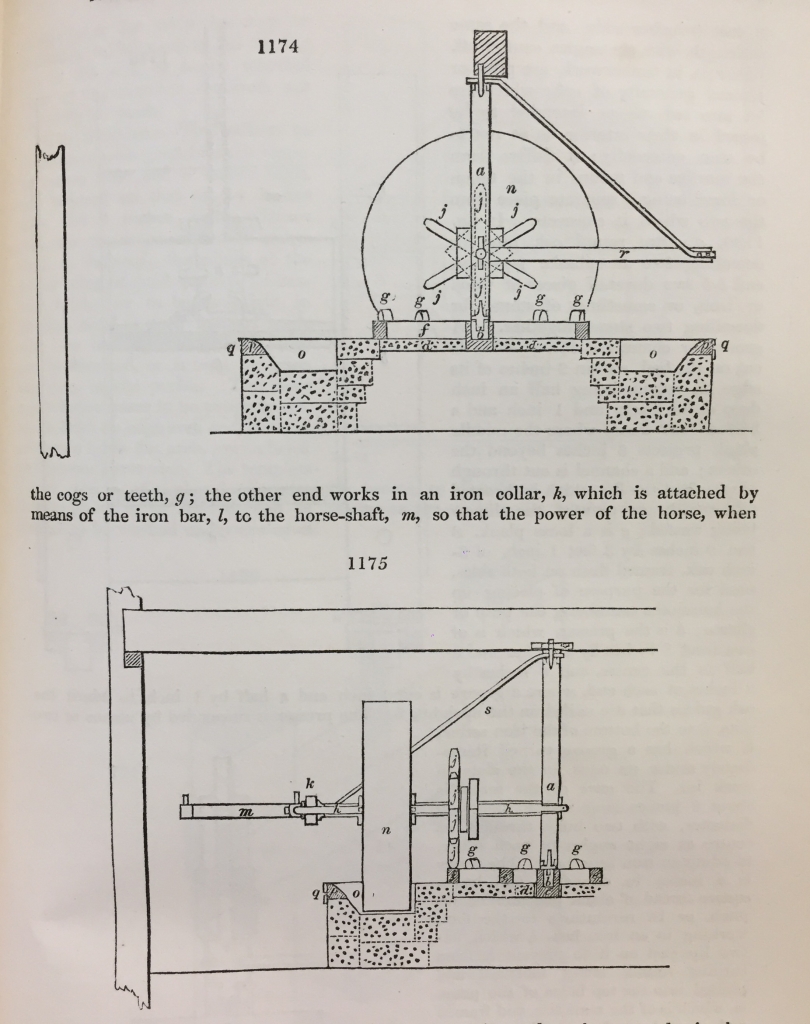

Essentially the same design for a cider mill was published by our favorite 19th century workaholic, John Claudius Loudon, in his ‘Encyclopaedia of Farm, Cottage and Villa Architecture’. These illustrations are from the 1869 edition, though the same appear in the 1830s. The only real difference is that in Loudon’s example the horse-powered millstone turns counter-clockwise, at Woolmer’s its clockwise:

Cider mill. Fig 1181 from Loudon’s Encyclopaedia (1869 edn.).Caroline Simpson Library & Research Collection

Cider mill construction. From Loudon’s Encyclopaedia (1869 edn.) Caroline Simpson Library & Research Collection

Round and around and around….

So how were these used to produce cider? Its pretty much as you’d think, though with some finessing. The trough – called the ‘chace’ – is where the fruit is placed. Loudon noted that some millstones had a slightly uneven or rough base, so that a majority of the kernels or seeds weren’t crushed into the pulp. The millstone rolls around the chace, which has a sloped outer rim. This meant that fruit could “work up on that side when the roller passed over it, as being more convenient for the driver [of the horse] to push it down again to be re-crushed.” This reduced the risk of fruit being pushed up and over the rim, and it was easily pushed back down. A mil of this type, he writes, could process around 90 bushels of fruit a day, to produce “3 hogsheads of cider, of about 1000 gallons each” – that’s around 3,785 litres. That’s a LOT of cider, so we’re not talking home consumption here.

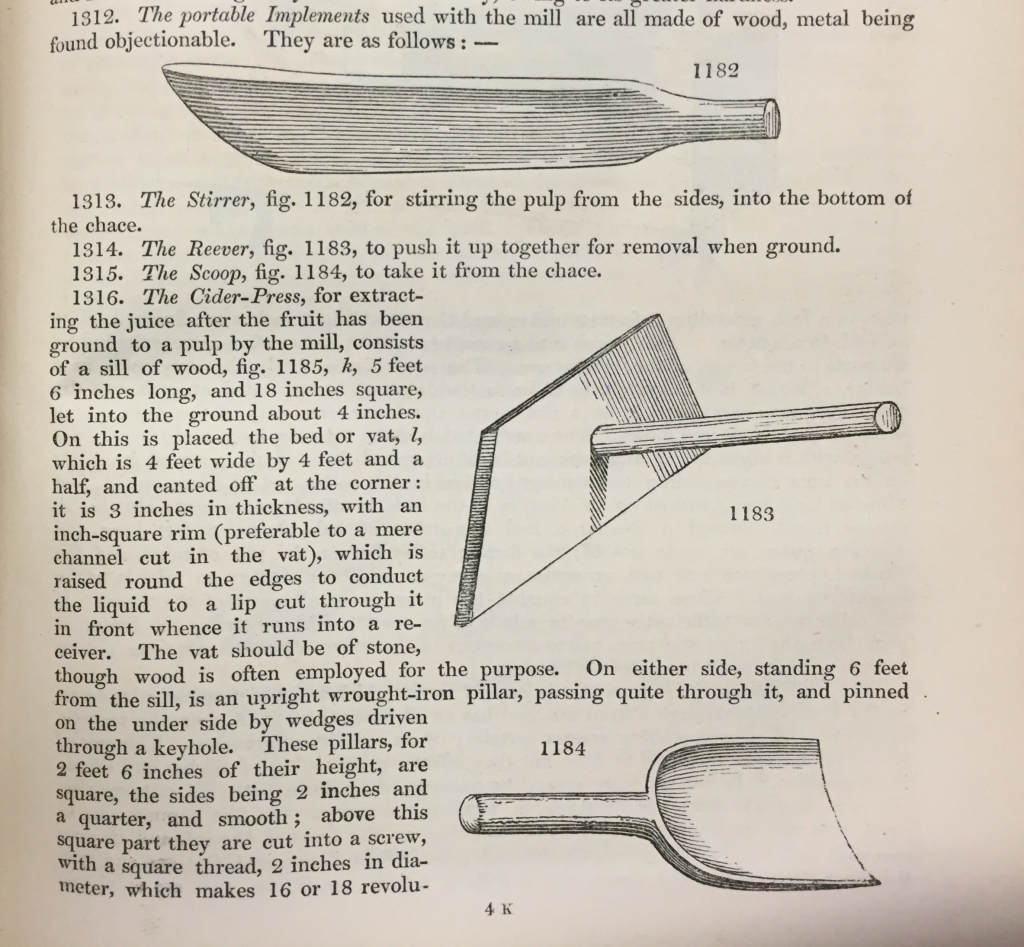

Loudon also details the equipment used. The ‘stirrer’ was used to push fruit back into the chace; the ‘reever’ which pushed the crushed fruit together has a distinctive shape, which matches the profile of the chace; the fruit was then scooped up by a – wait for it – ‘scoop’:

“The wheel being set in motion, a boy or girl (and one of ten or twelve years old can efficiently perform the office) continually follows the runner, pushing down the pulp by means of the stirrer, from the sides of the chace, up which it is continually squeezed, in order that it may again be crushed by the next revolution of the wheel.”

Cider mill implements. From Loudon’s Encyclopaedia (1869 edn.). Caroline Simpson Library & Research Collection

…and into the press:

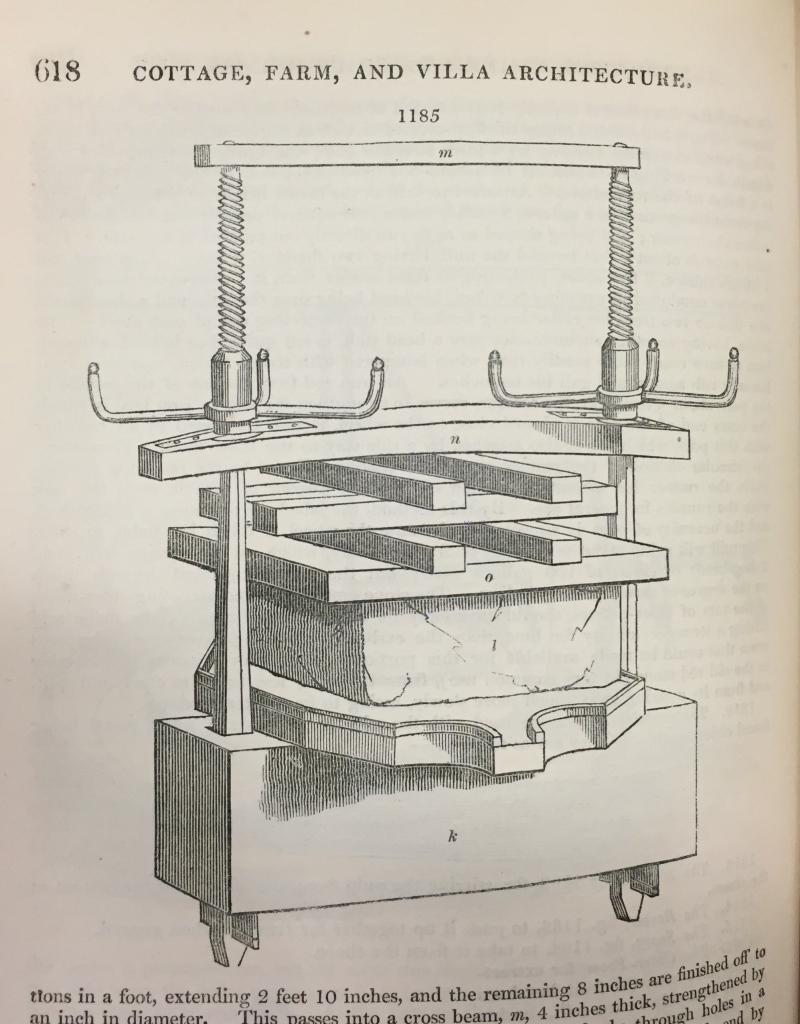

The quality of the cider, both taste and colour, was improved by letting the pulp sit in a tub for 24 hours. It was then placed into hair-bags and put into a cider press. Operating on the same principle as a clothes press, a long handle screwed the top down, the pressure forcing the liquid out of the pulp. Ever the innovator, Loudon suggested this two-handled version, which provided a greater and even pressure:

Design for a twin-screw cider press. Fig. 1185 from Loudon’s Encyclopaedia (1869 edn.). Caroline Simpson Library & Research Collection

The residue – “called must or cheese” – was then put back into the mill for a second crushing. The dregs could be used to produce what Johnson called ‘Ciderkin’:

“A low word used for the liquor made of the murk or gross matter of apples, after the cider is pressed out, and a convenient quantity of boiled water added to it; the whole confusing for about 48 hours” Samuel Johnson, 1755

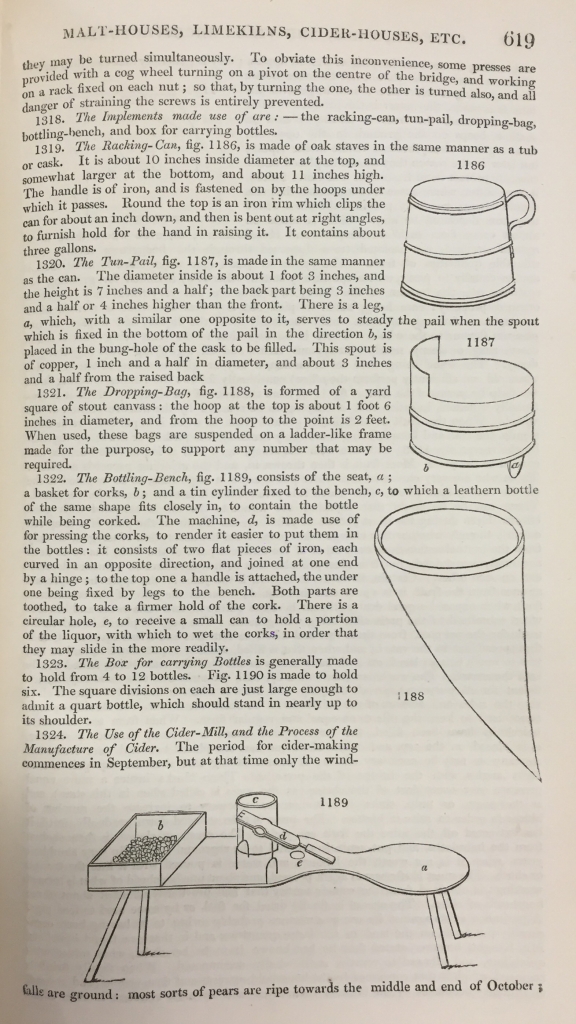

Sounds.. um… delightful… The final residue could be dried for use as a fuel “or by some fed to pigs”. Wentworth also noted this: “The lees, too, after the extraction of the juice, possess the same fattening properties, and are equally calculated as food for hogs“. Loudon then goes on at length about the process of barelling into hogsheads to ferment, and the clarification process using ‘dropping bags’ (the same principle as a jelly bag, though using canvas not flannel) to remove any residue that would spoil the cider as it fermented. Bottling, he states unequivocally, “must be done in the spring“. Drinking at any time. Cheers!

Cider bottling equipment. From Loudon’s Encyclopaedia (1869 edn.). Caroline Simpson Library & Research Collection

[1] A slight typo in the original, which should read ‘ultramontanians’, or those ‘beyond the mountains’.

[2] W C Wentworth, Description of the colony of New South Wales (&c.), London, G. & W. B. Whittaker, 1819

[3] See Woolmers website: the outbuildings http://www.woolmers.com.au/the-outbuildings retrieved 20th April, 2016

Text and images from Loudon’s encyclopaedia of farm, cottage and villa architecture (London, Frederick Warne & Co., 1869), one of several editions of Loudon’s tome held in the Caroline Simpson Library & Research Collection,.