Now that your dough has had a chance to rise it’s time to heat the oven and get baking!

In England in the 19th century the adulteration of foodstuffs such as flour was a serious issue – think of the melamine scandal in adulterated milk in China few years ago for a modern parallel. Eliza Acton’s The Bread Book was one of many publications that sought to address this issue in the case of bread, and attempts made to stamp it out. Commercially bought bread could be excellent, but it could also be dreadful, if not downright harmful. As a solution based simply on having control over the production process (and with a good dose of Victorian domestic morality thrown in), Acton writes in praise of home-made bread:

…certainly, no bread seems so sweet and wholesome as that which is so baked in private families, when perfect cleanliness has been observed in all the operations connected with it, and they have been performed with care and skill.

Baking bread of course required an oven. While for many colonial houses this took the form of a Dutch Oven nestled into the coals, the most common form of dedicated oven for the 18th and indeed much of the 19th century – until they were replaced by well-designed cast iron ovens – was the brick, slightly domed ‘beehive’ shape. You can spot their distinctive rounded outline and thick walls in house plans, such as this 1826 drawing by Henry Cooper for John Macarthur’s un-built villa at Pyrmont:

Plan of a subterranean kitchen with baking oven in the corner, detail of Plan basement and ground stories at Pyrmont (recto) by Henry Cooper, April 1826. State Library of NSW PXD 188 f41

While at Elizabeth Farm the Macarthurs were buying in loaves from Parramatta bakers, for households further from the town baking bread was part of the rhythm of daily life. In larger houses baking ovens are a common fixture in their service wings, identified by their small iron doors set into brick walls. They all feature considerably thick brick walls, which stored the heat from the fire lit within them. Loudon describes their construction:

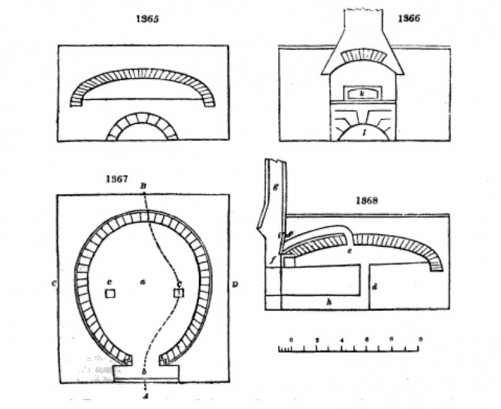

Plans for bread ovens, from J C Loudon, An encyclopædia of cottage, farm, and villa architecture and furniture, Longman, Brown, Green, & Longman, London, 1842. Google Books

An Oven for baking Bread is essential to every country inn; and in the same oven it will generally be found that meat can be roasted, in large quantities, more economically than by any other means… The ordinary size of bakers’ ovens is from eight to twelve feet square; those of confectioners are smaller, and frequently higher, with portable shelves of iron. The height of a baker’s oven is about eighteen inches in the centre, in ovens of the smallest size, and two feet in those which are larger. The lower and flatter the arch is, the more easily is the oven heated, and the more equally does it give out its heat. The sides of the oven need never be higher than a foot; that height giving sufficient room for a large loaf, and there can be no reason why the roof of the oven should be higher in the centre than at the sides except that it is impossible to build the soffit of an arch perfectly flat [a ‘flat arch’ is actually quite possible, but a curve is far easier to make and does not require purpose-formed bricks]. The floor of the oven is laid with tiles, and the arch is formed of fire-brick, fire-stone, or trap, set in fire-clay, or in loam mixed with powdered brick. The whole is surrounded by a large mass of common brickwork, to retain the heat. [1]

(Mrs Beeton however was of the opinion that meat baked in an oven was decidedly inferior – and tasted odd – to that roasted before the stove on a spit or bottle jack.) At Rouse Hill (in the ‘arcade’) and Camden Park (the rear service court) these bread ovens survive. That at Camden has a flat back wall, and slightly curved sides, like a section through a wine barrel:

Interior of the bread oven at Camden Park. Photo © Scott Hill

This oven is at Brickenden in Tasmania, one of the Australian Convict Sites on the World Heritage List along with the Hyde Park Barrack in Sydney. Unlike Camden’s more rectangular plan and vaulted ceiling, this is a more spatially interesting oval plan, often called a beehive oven:

Bread oven and bakers peel in the cookhouse at Brickenden, Tasmania. Photo © Scott Hill

Interior of the bread oven in the cookhouse at Brickenden, Tasmania. Photo © Scott Hill

The reason for the oval shape – the type seen in Cooper’s plan – was that it ensured an even heat. There were no corners to create temperature imbalances. The curved top, apart from being a standard means of construction, also facilitated air circulation within the chamber.

So how were these ovens used?

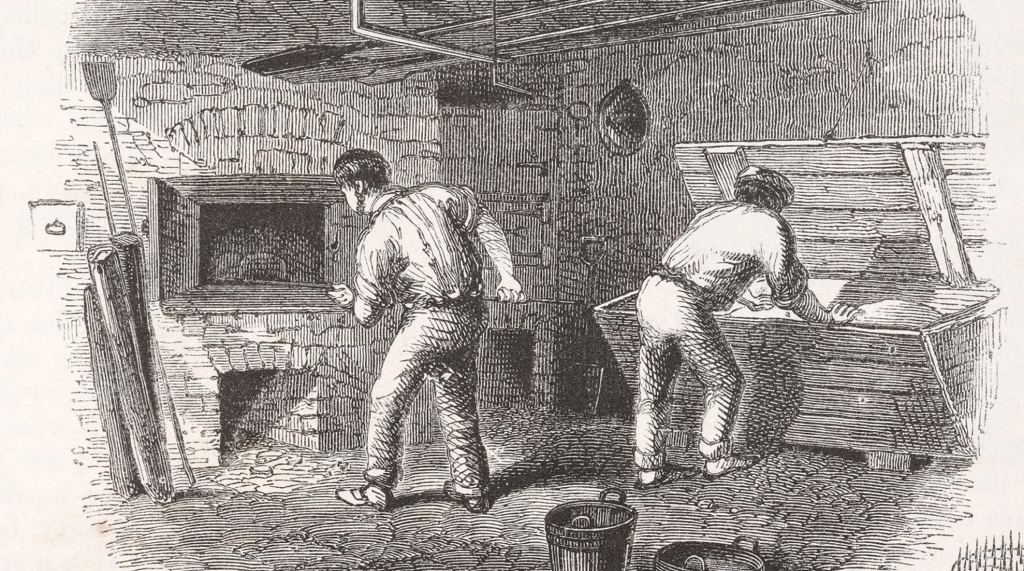

‘Baking oven and kneading trough’ (detail) from Charles Tomlinson, Illustrations of useful arts, manufactures, and trades, Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, London, [1858]. Caroline Simpson Library & Research Collection, Sydney Living Museums RB 331.76 TOM

Management of a brick oven. —

Of all [the types of bread oven] that are in common use amongst us at present, a brick oven, heated with wood, is generally considered as the best adapted to it…

To heat a large brick oven.—Lay a quantity of shavings or other dry light fuel into the centre of the oven, and some small branches of faggot-wood upon them; over these place as many of the larger branches as will make a tolerably large fire, and set light to the shavings. As the wood consumes keep adding more, throwing in, after a time, amongst the live embers the stout poles of the faggot, and, lastly, two or three moderate-sized logs of cord-wood, when the oven is of large dimensions and the heat is wanted to be long-sustained…

From an hour and a half to two hours will be required to heat thoroughly a full-sized brick oven. The fire should be spread over it in all parts towards the end of the time, that the whole of the floor may be in a proper state for baking.

After all the embers and ashes have been cleared out, a large mop, kept exclusively for the purpose, dipped into hot water and wrung very dry, should be passed in every direction over it, to cleanse it perfectly for the reception of the bread. As the heat is greatest at the further part of the oven (and at the sides frequently), it is usual to place loaves of the largest size there, and those which require less baking nearer to the mouth of the oven.

To ascertain whether a brick oven be heated to the proper degree for baking bread, it is customary for persons who have not much experience to throw a small quantity of flour into it. Should it take fire immediately, or become black, the oven is too hot*, and should be closed, if the state of the dough will permit it to wait, until the temperature is moderated: this is better than cooling it down quickly by leaving the door open. It may also be tested by putting into it small bits of dough about the size of walnuts, which will soon show whether it be over heated or not sufficiently so.

(Flour dust is actually highly flammable, even explosive – as London discovered to its horror in 1666 when a certain bakery in ‘Pudding Lane’ caught fire… ) The bread, usually held in a tin to give it a regular shape, was then slid in and out when ready using a long handled, flat-bladed bakers peel.

If you look at the Camden oven (and note how thick the wall is) you’ll see a second opening at ground level:

Bread oven at Camden Park with hatch for the sweepings beneath. Photo © Scott Hill

This connects to a flue above into which the ash and coals are swept, to clear the oven ready for baking. You can see the ‘tunnels’ in Loudon’s drawings above.

Given the time required for heating the oven, mixing and resting the dough and then baking, we can estimate that the oven fire was lit no later 6am, for rolls to be ready by 10:30 am, when a genteel breakfast was served at Elizabeth Farm.

Thrift

And don’t waste the heat! It was common for those without ovens to pay to use their local baker’s ovens after the days baking was finished to cook their pies and meat joints, using the residual heat. Loudon suggested building a poultry house behind the oven, so that it could be warmed in winter. For domestic ovens Acton adds:

To ensure a sufficient degree of heat to bake bread properly, and a variety of other things in succession after it when they are required, the oven should be well heated, then cleared and cleansed ready for use, and closely shut from half an hour to an hour, according to its size. It will not then cool down as it would if the baking were commenced immediately after the fire was withdrawn, but will serve for cakes, biscuits, sweet puddings, fruit, meat-jelly, jars of sago, tapioca, rice, and other preparations, for several hours after the bread is taken out.

Treated with care, and maybe a top-up of heat, the oven was then still quite hot enough to prepare tasty items for the dinner table:

I have known a very large brick oven, heated in the middle of the day… still warm enough at eight or nine o’clock in the evening to bake various delicate small cakes, such as macaroons and meringues, and also custards, apples, &c. It is both a great convenience and a considerable economy in many families to have such a means of preparing food for several days’ consumption, and renders them entirely independent both of bakers and confectioners. [2]

Huzzah for independence from confectioners!

The crumbs:

[1] J C Loudon An encyclopaedia of cottage, farm and villa architecture. London, Longman, Brown, Green and Longmans. 1842. pp 719-20

Read the 1842 edition of the Encyclopaedia online here

[2] Eliza Acton The English Bread Book for domestic use adapted to families of every grade. London, Longman, Brown, Green, Longmans & Roberts. 1857

Read Eliza Acton’s The English bread book online here.

A typo that escaped attention has now been corrected – the Great Fire of London took place in 1666, not 1066. Oops! The Normans would have been surprised!