We’re gearing up for our FREE! Autumn Harvest celebration at Rouse Hill House and Farm this weekend, and we’ve been foraging through the Rouse Hill family cookery books and manuscript recipes to bring you a taste of life at Rouse Hill during colonial times and in the early 1900s. Inspired by the Harvest program, resident foodie, Jacky Dalton has been experimenting with tradition the of preserving cabbage – or,

There is only so much cabbage soup I can eat, now what?

Cabbages in the kitchen garden at Vaucluse House. Photo © James Horan for Sydney Living Museums

Seasonal stories

Cabbage is in season, and so now is the best time to harvest and enjoy this easy to grow vegetable. Cabbage can be found in food traditions dating back to the ancient Greeks, and many cultures have some connection with this abundant food crop, a tribute to its hardiness and health benefits. It is fortunate that it is an ideal vegetable for preserving, because there is only so much cabbage soup you can enjoy while it is at its harvestable peak. The most common forms of preserving cabbage are pickling and fermenting.

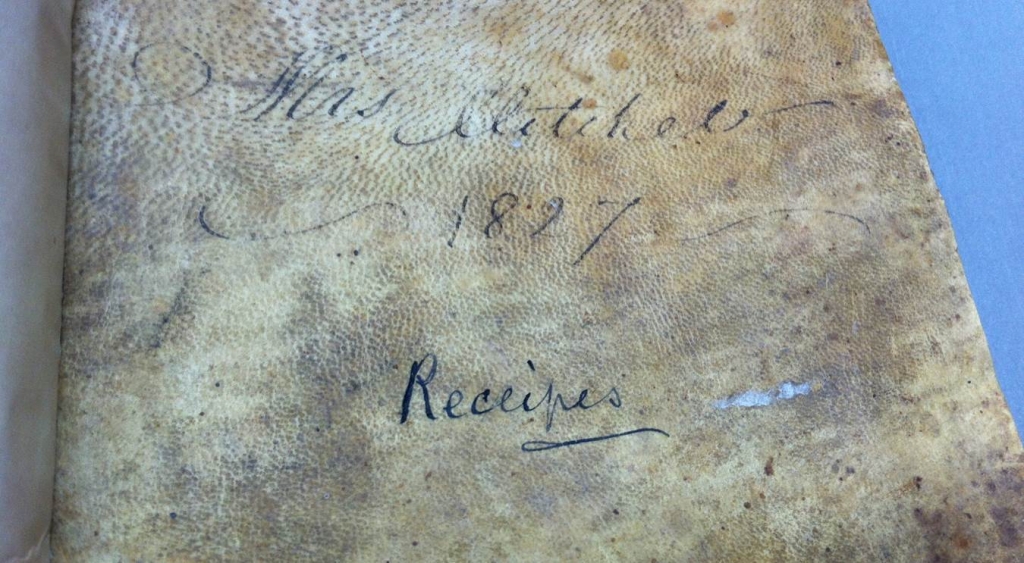

Mrs Mitchell’s recipes, 1827. State Library of NSW C 83. Photo Jacqui Newling © Sydney Living Museums

When Mrs Mitchell, wife of Sir Thomas Mitchell, arrived in the Colony in 1827, she brought with her a recipe book bearing the same date on the cover. It must have been put together as a parting gift, a reminder of the traditions of English cooking as well as a connection to the family and friends Mrs Mitchell left behind.

Tickled pink

As I was going through the hand written ‘receipts’ and cleaning tips, I noticed a recipe for red pickled cabbage, and the notable factor was the use of cochineal to produce an aesthetically pleasing red hue to the preserved cabbage. Up to now I had noted the use of beetroot for this purpose amongst some 19th century recipe books, and so I presumed this was a unique quirk of Mrs Blunt (probably Mrs Mitchell’s mother) whose name appears in the title of a few of the recipes.

However, when going through the Rouse Hill House and Farm collection of recipe books, I discovered that Nina Terry’s (nee Rouse) recipe book, Mrs Maclurcan’s cookery book (1903), also contained a recipe that used cochineal to ensure the vibrancy of pickled red cabbage. Before synthetic food colouring, cochineal was derived from the cochineal beetle; Mrs Beeton’s recipe for pickled red cabbage recommends:

a little bruised cochineal boiled with the

vinegar adds much to the appearance of this pickle

Beeton’s book of household management, 1861 p239

Fermenting vs pickling

Fortunately I have also discovered a less brutal process of preserving cabbage through fermentation, a practice that has experienced a recent revival due to its health benefits and a desire to return to a more seasonal and sustainable approach to the food we eat.

Rather than immersing the salted sliced cabbage in a vinegar to stop bacterial growth (usually with the addition of spices for flavouring), fermentation simply involves the salted cabbage being packed tightly into an airtight container and left to ferment. This allows the natural bacteria to grow, producing the probiotics that are important for good gut health. Even though the pickling may result in a similar flavour, it does not contain the same health benefits of true Sauerkraut.

Jacky’s pickled cabbage. Photo Scott Hill © Sydney Living Museums

Ask the experts

With the rebirth of this tradition, I found a recipe for Sauer Kraut in the same Mrs Maclurcan’s 1903 recipe book previously mentioned, that I thought utilised the fermentation process, distinct from another recipe for pickled cabbage in her book. I was interested to see how both methods compared with contemporary techniques so I went to Cornersmith Picklery’s fermenting teacher, Jaimee Edwards and showed her the recipes. Jaimee remarked:

most striking about these recipes is just how little methods have changed in over 100 years… proving that food crafts such as pickling and fermenting are methods that have been perfected over generations.

Jaimee Edwards of Cornersmith. Photo courtesy Cornersmith

Local talent

Cornersmith will be bringing Jaimee’s creations to our inaugural Autumn Harvest Festival on Sunday 31st May at Rouse Hill House and Farm. This Festival will feature 20 artisan food stallholders, selling and talking about, food that has been sourced and prepared using traditionally sustainable methods reflecting the practices that would have been used by the Rouse family at this special site.

Recipe cards showcasing recipes that have been sourced from the Rouse family collection will be available to collect, including the recipe for Sauer Kraut. If you can’t make it to the Festival, I have included the recipe below.

This is Mrs Maclurcan’s method for Sauer Kraut, sourced from Nina Terry’s (nee Rouse) Mrs Maclurcan’s cookery book (1903), p 462.

INGREDIENTS

1 large white cabbage

½ cup salt

cold waterCut the cabbage up very finely, as you would for pickled cabbage; put it into a very clean wooden tub; sprinkle the salt over and cover with cold water; put a weight on the cabbage to keep it under the water; tie the tub down with a cloth and allow the contents to ferment.

Please note: This recipe includes the same process as outlined in the original recipe book, but imperial measurements have been converted to metric measurements.

Interestingly, modern recipes do not usually require the addition of water as the cabbage will release a significant amount of fluid to cover the cabbage. Jaimee Edwards thinks that perhaps this is because we use air tight containers, while in 1903 the salted cabbage was put into a wooden tub, which might absorb some of the water.

Sauer Kraut would be added to corned beef as it heated in a saucepan with vinegar, water and spices such as cloves, ginger and black pepper added to flavour.