Just as we are all craving fresh salads in these warm summer months, so too were the residents of Susannah Place in The Rocks, in inner urban Sydney – who were likely to dress their salads with the then ubiquitous “salad oil”. Guest author Philippa Vaughan, Visitor and Interpretation Officer at Susannah Place Museum in The Rocks, writes about this surprising kitchen staple in Sydney’s early culinary history.

Bottles found at Parbury Ruins archaeological site. The dark green bottle on the left is a pickle bottle and the other two on the right are salad oil bottles. These bottles date back to the mid-1800s. Photo © Philippa Vaughn, Sydney Living Museums

Salad days

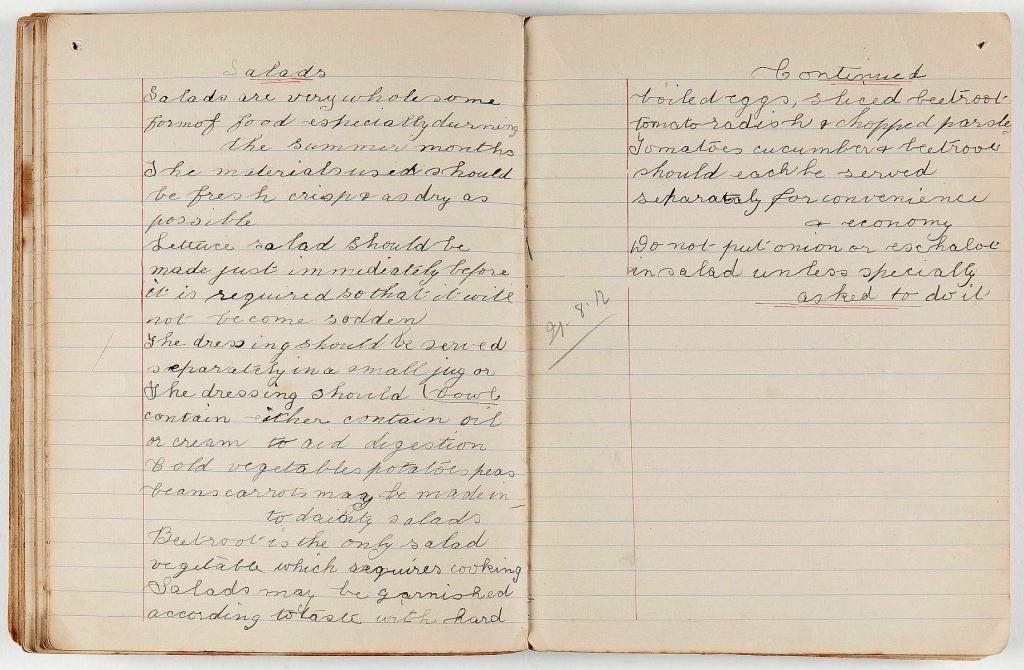

In August 1912, Susannah Place school girl, Dolly Youngein was learning the principles of making a good salad at her local Fort Street Public School cookery classes, writing out the recipe for ‘salads’ in her homework book:

“Salads are a very wholesome form of food especially during the summer months. The materials used should be fresh, crisp and as dry as possible.

Lettuce salad should be made just immediately before it is required so that it will not become sodden.

The dressing should be served separately in a small jug or bowl. The dressing should contain either oil or cream to aid digestion.”

Dolly Youngein 21.8.1912Notes on ‘Salads’ from Dolly Youngein’s cooking homework book, Fort Street School, Courtesy John Brown. Photo © Jamie North for Sydney Living Museums

Dolly’s book does not provide recipes for dressing but other cookery texts indicate popular options from the times: salad ‘cream’ along the lines of Mrs Wiseheart’s salad dressing in the Meroogal collection made with butter and egg, or an oil-based dressings such as a mayonnaise-style emulsion or ‘vinaigrette’ style French and curiously, Russian dressings. Mrs Maclurcan’s Cookery Book (1903) includes several dressings recipes that specify olive oil, and best olive oil (see recipe below).

Eating well

By the time Susannah Place was built in 1844 The Rocks neighbourhood was in full swing with its own unique colonial food culture closely tied to the trade of imported goods on the harbour as well as British food traditions.

During the 19th century peach trees grew wild throughout The Rocks, small home gardens hummed with bees pollinating small crops of peas, beans and apple trees. The dinner table was often adorned with fine china while less aesthetic earthenware was used to cook the food. Families enjoyed diets high in meats such as beef, lamb, duck, chicken and oysters. Bakeries supplied fresh bread and you could even use the baker’s oven to cook your Sunday roast if you didn’t have your own facilities. Corner shops such as the “cheap cash grocer” that operated from the front room of 64 Gloucester Street in Susannah Place (shown below) sold a range of jams, pickles, chutneys, condiments, sauces and dressings to add extra flavour to people’s meals [1].

Cumberland Place Sept 1901, showing the rear of the ‘cheap cash grocer’ that operated from 64 Gloucester Street (now part of Susannah Place Museum). State Library of NSW: PXE921 Vol1 No21

Enter the olive

Contrary to popular belief, olive oil was fairly common in many colonial kitchens [2]. It is often assumed that olive oil only arrived as a food item with post World War II immigration, and although animal fats such as lard and dripping may have been the colonial cook’s prime choice for cooking, the digestive qualities and lighter flavour of olive oil were recognised in many kitchens. Edward Abbott, author of Australia’s first published cookbook said in 1864 that olive oil was ‘much used’:

“Olive is a fruit of the tree of the same name. It is pickled for use; and the olive pressed, produces the valuable vegetable oil so much used.”

The English and Australian cookery book: cookery for the many, as well as for the upper ten thousand, “by an Australian aristologist” Edward Abbott, 1864

As well as salad dressings, olive oil was used for frying fish and in the preservation of citrus juice.

Archaeological evidence found at sites throughout Sydney’s waterfront, including The Rocks and Millers Point, suggests that olive oil was being consumed continuously from early settlement [3].

Oily business

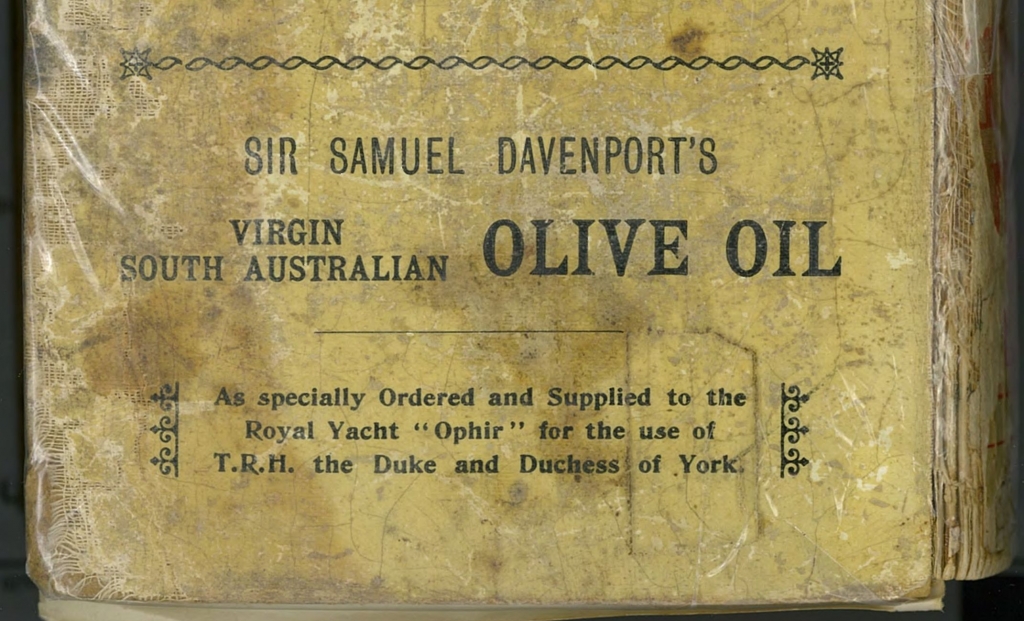

Advertisement for Sir Samuel Davenport’s Virgin South Australian olive oil on the cover of Mrs Maclurcan’s Cookery Book, 1905 edition. Photo © Sydney Living Museums

Despite large olive groves and oil production occurring in South Australia in the 19th century, the majority of olive oil consumed by Sydney-siders was imported from Europe [4]. In the early 20th century there was even a trade coming into Sydney of the best quality olive oil from California [5].

While olive oil was sold used and marketed for medicinal purposes by chemists it was predominantly used for culinary purposes, and sold in local grocers’ shops. Olive oil was often sold under other names, including Lucca oil (Lucca being an oil producing town in Italy) and the more generic ‘salad oil’ (the ambiguity of the name meant that many cooks – and subsequent researchers – may not have realised that it originated from the olive fruit) [6].

Salad oil

Newspaper advertisements and trade prices (see below) suggest that salad oil was a lighter oil than the product we know today as ‘extra virgin’ and in many cases may have been a blended oil, possibly mixed with cottonseed oil. Defending the purity of his South Australian olive oil in 1906, Sir Samuel Davenport noted that:

“The olive oil he had known in years gone by, [marketed] under the misleading name of salad oil, [was believed] to be pure olive oil. But now he knew there was a distinction drawn on the market between what was called salad oil, which used to be sold as olive oil, and pure olive oil as now bottled”

Adelaide Advertiser, Tuesday 31 July 1906, page 8

Salad oil bottle, excavated from beneath the ground floor of Hyde Park Barracks, Aged & Destitute Asylum period, 1862-1886. Photo © Jamie North for Sydney Living Museums

A competitive market

Salad oil was markedly cheaper than imported olive oil. In 1912 McIlrath’s Limited was selling ‘Finest salad oil’ by the half-pint (approximately 300ml) for five and a half pence, whereas ‘Finest imported “Rosa” olive oil’ cost almost double, nine and a half pence. Both were sold by the quart – 1/7 (shillings/pence) and 2/6 respectively, indicating that there was a demand for ‘the good oil’ as well as the more economical version [7].

Around this time, wholesale dealers were selling imported olive oil for between 3 and 3/6 per quart, and Italian Lucca (grades C and B) for 1/6 per pint and 3 shillings per quart. South Australian olive oil presented a relatively cheap option for buyers at 1/8 per quart or 1/3 per pint [8].

The volumes being advertised – pints and quarts by the dozen or by the gallon give a strong indication that the olive oil was widely used long before the 1950s post-WW2 migration.

‘My Salad Dressing’

Yolks of three hard-boiled eggs; 1 dessertspoonful of made mustard; 3 tablespoonfuls of condensed milk; 4 tablespoonfuls best olive oil; 3 tablespoonfuls malt vinegar; juice of a lemonPlace the yolks of the eggs in a bowl and rub them perfectly smooth with a wooden spoon , then add the condensed milk and mustard; when these are nicely mixed add half of the oil, a drop at a time, stirring well the one way all the while, then half the vinegar, also a drop at a time.

Now put in the rest of the oil and vinegar, being careful to drop it in; this ought to be the thickness of good cream. Lastly, add the juice of a lemon.

To make this dressing well it will take nearly half an hour. Stand it in a cool place until required. If in hot weather place it in the ice chest.

Mrs Maclurcan’s cookery book, Rouse Hill House & Farm collection, 1902

*Philippa Vaughan is a Visitor and Interpretation Officer at Susannah Place Museum.

Sources and further reading

[1] The Big Dig Archaeology Education Centre – https://thebigdig.com.au/thebigdig/site/

[2] Hill, Craig. Towards a history of the olive industry in South Australia, 1998, p4

[3] Casey and Lowe Pty Ltd, prepared by Jeanne E. Harris, Glass Report: Darling Quarter (Walk) Darling Harbour Sydney, 2010

[4] Hill, Towards a history of the olive industry in South Australia, p2-3

[5] The Evening News, Sydney, 13 June 1902

[6] Sydney Morning Herald, February 16, 1912, p6

[7] ‘General Merchandise’ Sydney Morning Herald February 27, 1912 p11