According to French gourmand, Grimod de La Reyniére, ‘spices are the soul, the hidden spirit of good cookery‘. [1]

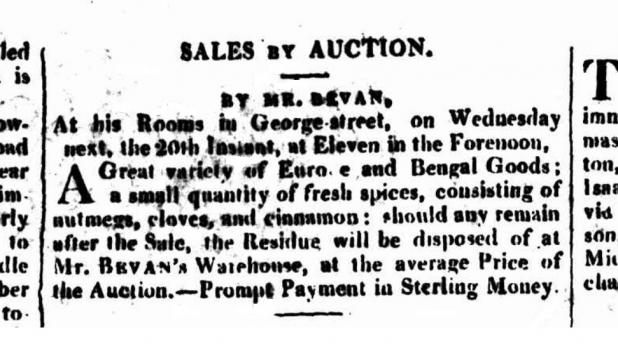

Early colonial auction advertisement listing familiar spices. The Sydney Gazette 16 December 1815. Source: Trove

Contrary to the popular belief that colonial food was plain, boring and bland, spices were readily used in Sydney’s early kitchens. Newspaper advertisements give us an idea of what was available, recipes tell us which and how spices were being used for what dishes, and even more telling, spice containers – boxes and canisters – that show wear and tear indicate what was actually being used by cooks. Over the next few weeks we will be highlighting a selection of culinary spices – fresh and dried, from the delicate to the pungent, aromatic to hot and how they were used -with a few diversions along the way to spice things up!

Two tiered Japanned spice canister set. Rouse Hill House and Farm collection. Photo © Sydney Living Museums

The spice palette

Dating from around the mid-19th century, this handsome ‘Japanned’ or black-lacquered metal spice caddy, or canister set, belonged to the Rouse family of Rouse Hill House. It houses ten wedge-shaped containers positioned around a central tube, which would have accommodated a cylindrical nutmeg grater whose location is unknown. The latch on the outer canister matches those on a set of single flat lidded canisters for flour, sugar, rice etc which also seen in the kitchen at Rouse Hill House today. Heavy wear and some deterioration of the metal and Japanned coating have obscured the lettering on all but two inner containers, which read cayenne and cinnamon.

Japanned spice containers from a two tier spice caddy, circa 1850s. Photo © Jacqui Newling. Note the effects of wear on the more often used upper layer of containers.

A matter of taste

I have an almost identical spice canister in my collection of kitchen paraphernalia with more legible markings: allspice, cinnamon, clove, ginger, mace, nutmeg, three different peppers – black, white and long, plus cayenne – which is a chilli powder but commonly called ‘cayenne pepper’, and which remarkably, still has its nutmeg grater. It is unclear whether the spice tins came ready-labelled, or if they could be compiled to order, but the labels give us a good indication of what spices the manufacturer or owner expected would be most commonly used.

The disparity in wear on the individual boxes gives a good indication for which spices were favoured by the set’s past owner[s] – black pepper clearly more readily used than the other types and allspice, clove, ginger and mace very well worn. Cinnamon and nutmeg boxes are curiously unsullied – perhaps because they were used in their whole form rather than ground, and needed a larger container? Indeed, it seems the lower layer of spice tins barely saw the light of day, well preserved from residual oils from the cook’s hands which have discoloured their upper counterparts.

C19th tin spice caddy with selection of popular spices. Photo © James Horan for Sydney Living Museums

Foundation spices

This popular repertoire could be used to create sweet and savoury blends. Maria Rundell’s ‘kitchen pepper’ (recipe below) is a good example of a savoury blend using commonly available household spices. Increasingly popular as the C19th progressed were curry powder blends, made with the addition of some more ‘exotic’ spices – turmeric being the vital ingredient, and others such as cumin or cardamom, which are conspicuous in their absence in the ‘standard’ household spice palettes. Also missing are seeds derived from herbs such as coriander, parsley, dill, fennel or mustard, but which could be readily harvested from a domestic herb patch as the plant went to seed.

Kitchen pepper

Ingredients

- 30g ground ginger

- 15g ground cinnamon

- 15g ground black pepper

- 15g ground allspice

- 15g ground nutmeg

- 1 teaspoon ground cloves

- 170g salt (optional)

Note

This pungent blend of spices is from A new system of domestic cookery, by Maria Rundell (1816). The original recipe adds salt, which you may prefer to omit, adding salt to taste, in whatever dish you are cooking. Use in slow cooked meat dishes, 'brown' sauces, gravy or soups, for depth and complexity.

As with any spice blend, particularly those from past times, we cannot know the age, quality or pungency of the spices, so adjust to your liking.

Directions

| Combine all ingredients and mix well. Store in an airtight jar, allowing a few days before using for flavours to meld. Use to taste. As with most pre-ground blends, if made with good quality spices, the mixture will keep for approximately 18 months before losing its flavour. | |

Sources:

[1] Giles MacDonogh. A palate in revolution : Grimod de La Reyniére and the Almanach des gourmands. London : Robin Clark, 1987. p.209

[2] Edward Abbot. The English and Australian cookery book for the many and the upper ten thousand. 1864. (The first known published cook book published by an Australian author. Now available in facsimile through TasFoodBooks.

Print recipe

Print recipe