Famous for ‘evicting’ his mother and father and unmarried sister from Elizabeth Bay House in 1845, William Sharp Macleay (1792-1865) remained as master of the house for another 20 years.

A distinguished man of science, William Sharp Macleay was well regarded among the intellectual circle in Sydney, and regularly entertained eminent scientists who visited Sydney from around the globe.

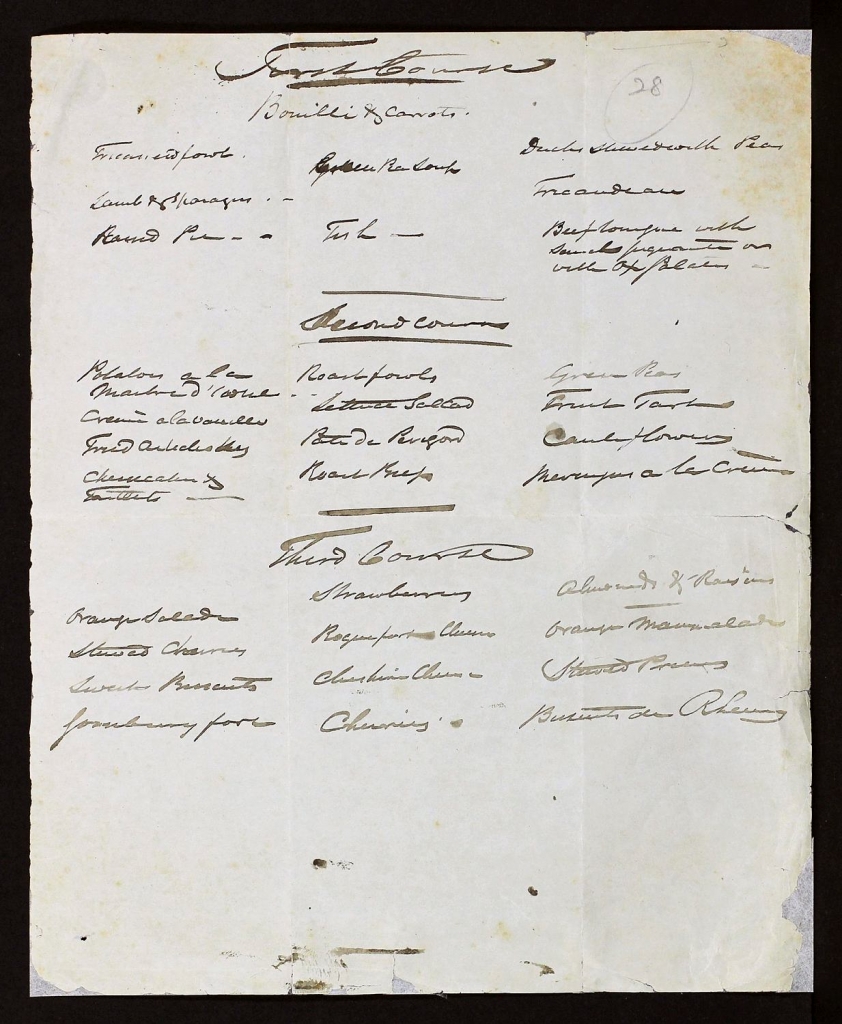

A dinner of thirty-three dishes

A rare handwritten menu drafted by William Sharp Macleay survives from 1859, held with his papers in the Linnaean Society of London Collection.

It is unknown how many guests were invited, but thirty-three dishes were to be served in three courses. Typical of its day, the menu is written in a symmetrical pattern, suggesting the way the dishes would be arranged on the table, à la Française style.

First Course

Fricasséed Fowls Bouilli & Carrots Ducks stewed with Peas

Lamb & Asparagus Green Pea Soup Fricandeau

Raised Pie Fish Beef tongue with sauce piquante (as with Ox Palates)

Second Course

Potatoes a la Maître d’Hôtel Roast fowls Green Peas

Crème a la Vanilla Lettuce Salad Fruit Tarts

Fried Artichokes Paté de Pigeon Cauliflower

Cheesecakes & Tartlets Roast Beef Meringues à la Crème

Third Course

Orange Salade Strawberries Almonds & Raisins

Stewed Cherries Roquefort Cheese Orange Marmalade

Sweet Biscuits Cheshire Cheese Stewed Prunes

Gooseberry fool Cherries Biscuits de Rheims

Setting the scene

You can see us setting the table for second course of this menu here or below.

A seasonal harvest

The seasonal produce suggests it was for a spring time dinner, much of it supplied from the estate’s kitchen garden. Many households bred their own livestock, pigeons, ducks and fowl for the table, or acquired them from Sydney markets. Imported cheese rounded out the dessert course. When you visit Elizabeth Bay House today, you can view the basement kitchen and imagine the industry and coordination required to produce such a meal – and imagine how often the kitchen maids ran up and down the stairs to deliver them to the butler’s pantry so that he could present them at the table.

Menu written by William Sharp Macleay at Elizabeth Bay House, circa 1860. © Linnean Society Collection, London.

The French influence

It wasn’t just the dining style that was borrowed from the French! French terms were often used on colonial menus, indicating the influence that French cuisine had on English tastes, but also elevating the status of a meal event, with the assumption that all at the table understood the foreign terminology. Quite often the dishes followed simple techniques: a fricassée is basically sauteed meat which is then cooked in a sauce; bouilli – literally stock, as in bouillon, meat, usually beef, cooked in stock – so a stew; fricandeau is similar, larded veal poached in a rich sauce; potatoes prepared a la maître d’hôtel are boiled then thickly sliced, then tossed through butter, stock and parsley. Dishes prepared this way, ready sliced or portioned are easy to share among guests at the table.

And finally note the combination of substantial sweet and savoury dishes served in second course – the idea of roast beef sitting alongside cheesecakes and meringues is quite bizarre (though I know a few preschool children who would think it most appropriate!). These days the sweet dishes are reserved for dessert, but even when the sweet and savoury dishes were separated later in the 19th century, a ‘dessert’ course followed the sweets course to conclude the meal – usually cheese, fruit and a selection of small savoury morsels.

William’s dinner was hosted the same year that Mrs Beeton started publishing her recipes in magazine form; The Book of Household Management followed as a single text in 1861. I’ve used her recipe for orange salad, because the inclusion of muscatels would have pleased William greatly – he had a sizeable vineyard which produced table grapes at Elizabeth Bay.

Orange muscatel salad

Ingredients

- 60ml (1/4 cup) brandy (or diluted to taste)

- 2 tablespoons white granulated sugar

- 1 cinnamon quill

- 100g dried muscatels (or sun raisins), stalks removed

- 4 oranges

Note

An orange salad was included in the final cheese or 'dessert' course on the menu for a dinner party hosted by William Sharp Macleay at Elizabeth Bay House in 1859. This recipe is adapted from Mrs Beeton's Orange salad (1861). It makes a nice accompaniment to turkey or pork.

Serves 6

Directions

| Warm the brandy, sugar and cinnamon in a saucepan over low heat, stirring gently for 5 minutes or until the sugar dissolves. Remove from the heat, add the muscatels and set aside until they have plumped up and the mixture has cooled. | |

| Squeeze and strain the juice from one orange, and add the juice to the brandied muscatel mixture. Peel the three remaining oranges, removing any pith, and either break the flesh into segments or slice into clean ‘wheels’ . Place the orange pieces in a shallow bowl and, keeping the cinnamon quill aside for garnish, pour over the muscatels and their liquor. And, as Mrs Beeton directs, 'mingle them' together. | |

| Transfer the salad mixture to a serving dish and garnish with the cinnamon quill. | |

Print recipe

Print recipe