At Elizabeth Bay and Vaucluse Houses we are often asked about some large elaborate boxes seen in the dining rooms: introducing the esky of the 19th century – the ‘cellaret’.

‘Little cellars’

Looking for all the world like an ‘esky’ [1] par excellence, cellarets (literally ‘little cellars’) were an innovation of the mid 18th century to store bottles in the dining room before use. They were a lidded version of the earlier open-topped ‘cistern’, and were designed to sit between the legs (and later the pedestal sides) of a sideboard, and so were often made ensuite (in the same style). Liners made of lead, zinc or copper, and occasionally of marble, sat inside the wooden case and could hold cold water (or, in a much colder climate, snow or crushed ice) to chill wine and champagne bottles prior to table use. But if you thought they had a certain ‘grave’ feeling to them, you’d be right!

Sideboard at Elizabeth Bay House with a lion-footed sarcophagus sitting between its pedestal sides. Courtesy Country Threads Magazine © Express Publications Pty Limited

A grave source for design

Though quickly available in every revival style possible, cellarets in the late 18th and early 19th century were typically designed in neoclassical styles. The term ‘sarcophagus’ was also used generically for cellarets in the 19th century, and this reflects the classical models adapted for their form: Roman funerary or cinerary boxes which originally contained cremated remains – the Romans preferring cremation rather than inhumation. Illustrations such as Piranesi’s (1720-1778) views of funerary monuments and remains from the surrounds of Rome (‘Le Antichita Romane’) [2] and publications by antiquarian societies such as the British Society of Dilletanti provided a wealth of inspiration for designers. Lion’s paw feet, acanthus and anthemion (honeysuckle) motifs were common decorative elements.

Romans cinerary urns or boxes from the first and second century often resembled Roman altars with corner horns (more generally in eastern Mediterranean examples) or (in western examples) cylindrical ‘pulvini’ rolls to the sides, curved tops and rams heads or ‘bucrania’ (ox skulls) to the corners with garlands strung between. The ‘Lenos’ form of Roman sarcophagus features lion heads on the sides, and these also appear commonly on cellarets. This late 18th century drawing by Carlo Labruzzi shows a variety of altars and cinerary boxes (one round urn can be seen at centre).

A collection of classical tombstones and other sculptural fragments from the Vigna Casali, Rome by Carlo Labruzzi, 1789-1794. © Trustees of the British Museum 1955, 1210.10.14

This mid 19th century tomb monument from Hobart repeats the form:

Pattern book examples

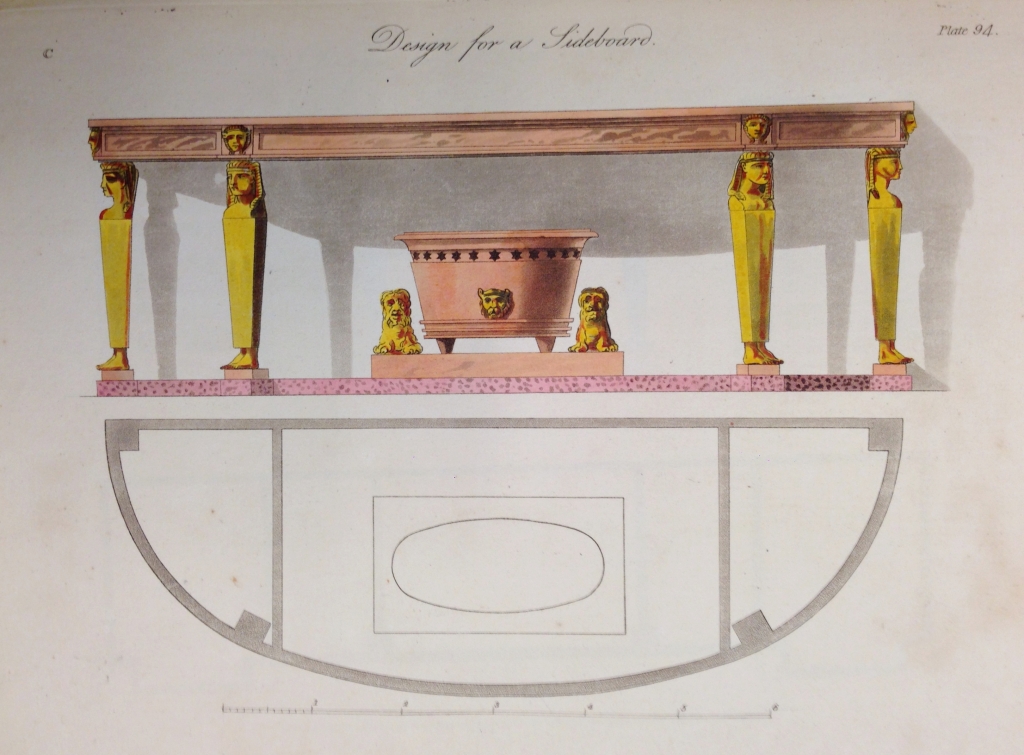

A browse through the pattern books of the period shows a wide variation of forms: from the open-topped, barrel or bathtub-like ‘cooler’ or ‘cistern’ to elaborate, sepulchral examples. The first, from George Smith (1808) is in the Egyptian Revival style. It and the second example show cisterns like a hip bath with open tops which would suit being filled with ice or chilled water. (We’ve all been to parties where the bath tub or laundry sink is filled with ice for drinks; its the same principle, only a tad classier.) In the ice-free colony of New South Wales cold water retrieved from a deep well could be used instead.

‘Design for a sideboard’, from George Smith, Collection of designs for household furniture, J.Taylor, London, 1808. Caroline Simpson Library & Research Collection RBQ 749.2048.SMI

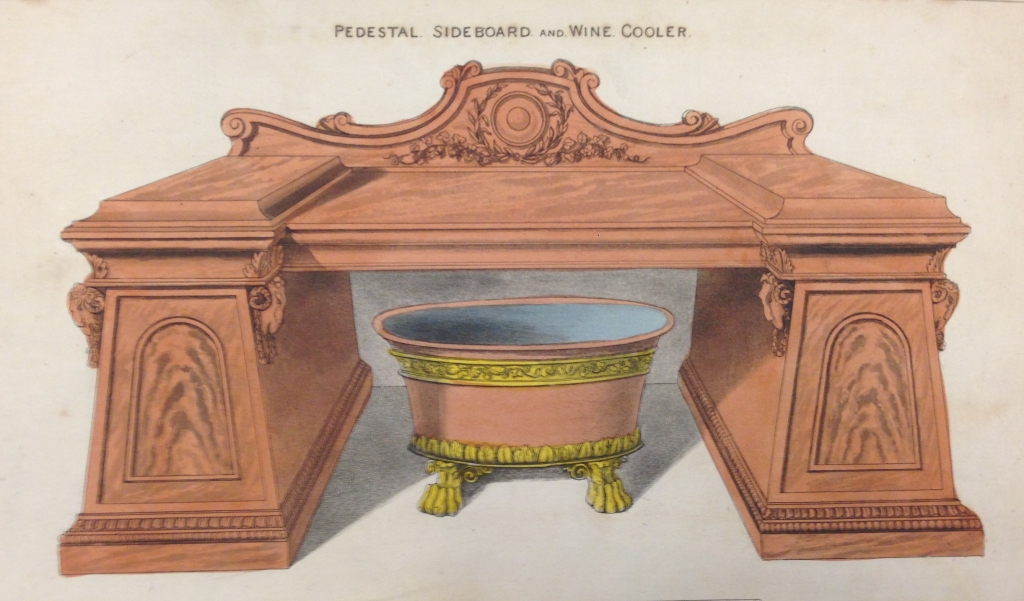

This lion-footed design is described by Smith as “A design for a pedestal sideboard… Under the centre is placed an oval open cistern lined with lead inside, intended for holding the ale and beer jugs, as well as to contain the ice for cooling the wine in hot weather”:

‘Pedestal sideboard and wine cooler’, Pl. LXXV from George Smith’s, Cabinet makers and upholsterers guide, J.Taylor, London, 1808. Caroline Simpson Library & Research Collection RB 749.2048.SMI

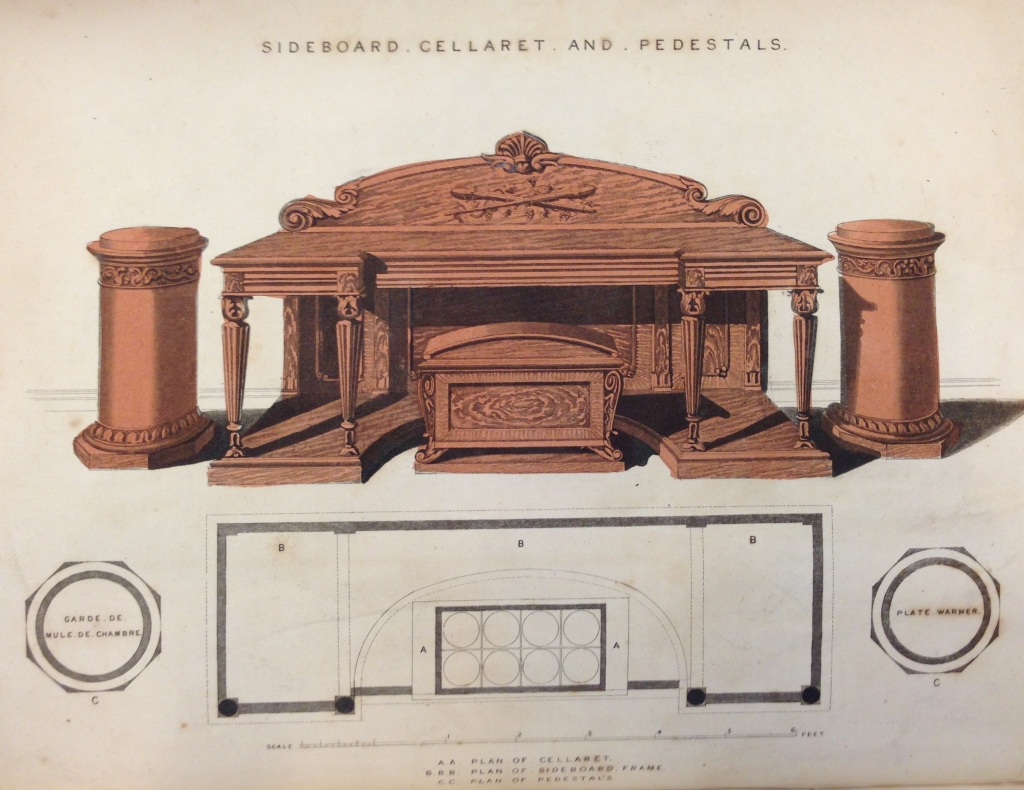

In the Greek Revival style, the plan of this design also shows either compartments or space for 8 individual bottles:

‘Sideboard, cellaret and pedestals’, Pl. IV from George Smith, Cabinet makers and upholsterers guide, J.Taylor, London, 1808. Caroline Simpson Library & Research Collection RB 749.2048.SMI

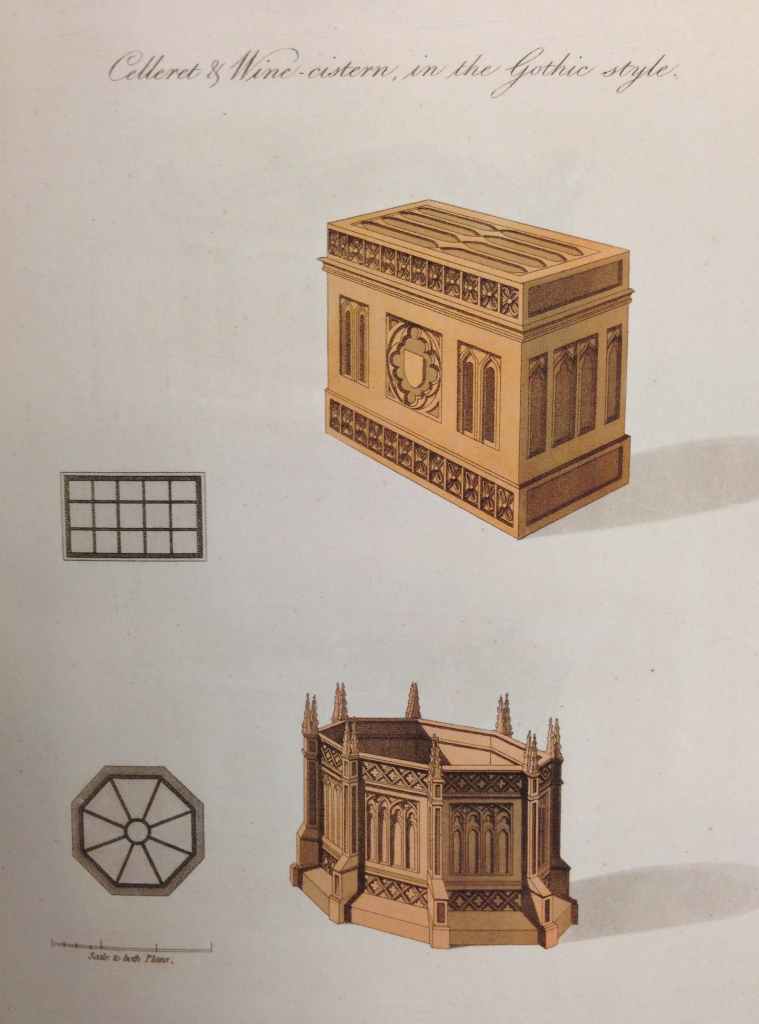

…while these designs, for a 15 bottle lidded cellaret and an open-topped, octagonal cistern are in the Gothic revival style:

‘Cellaret and wine cistern in the Gothic style’ from George Smith, Collection of designs for household furniture, J.Taylor, London, 1808. Caroline Simpson Library & Research Collection RBQ 749.2048.SMI

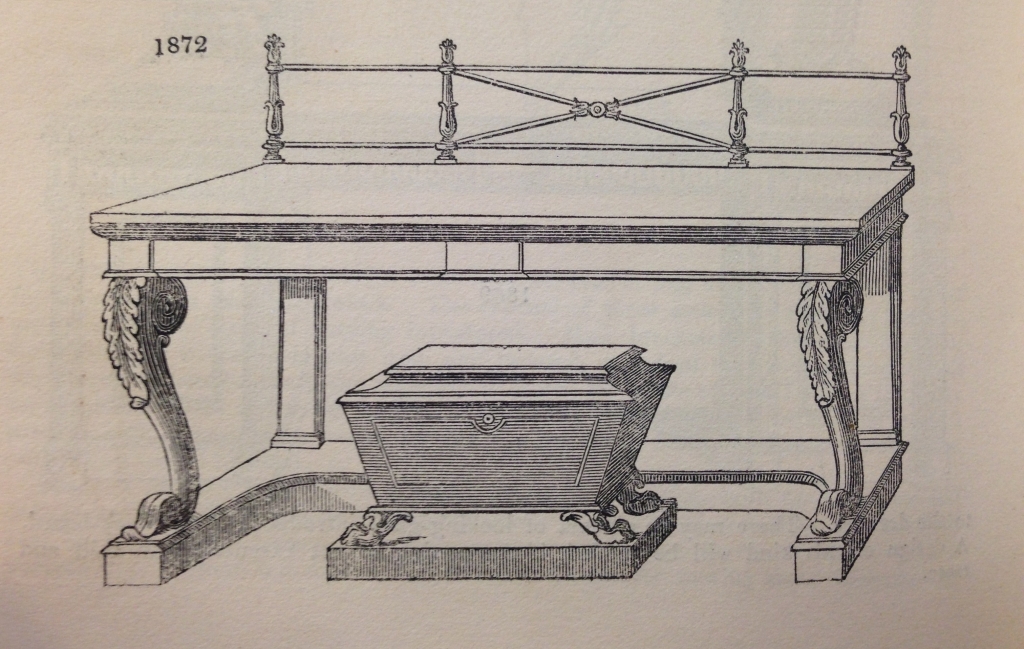

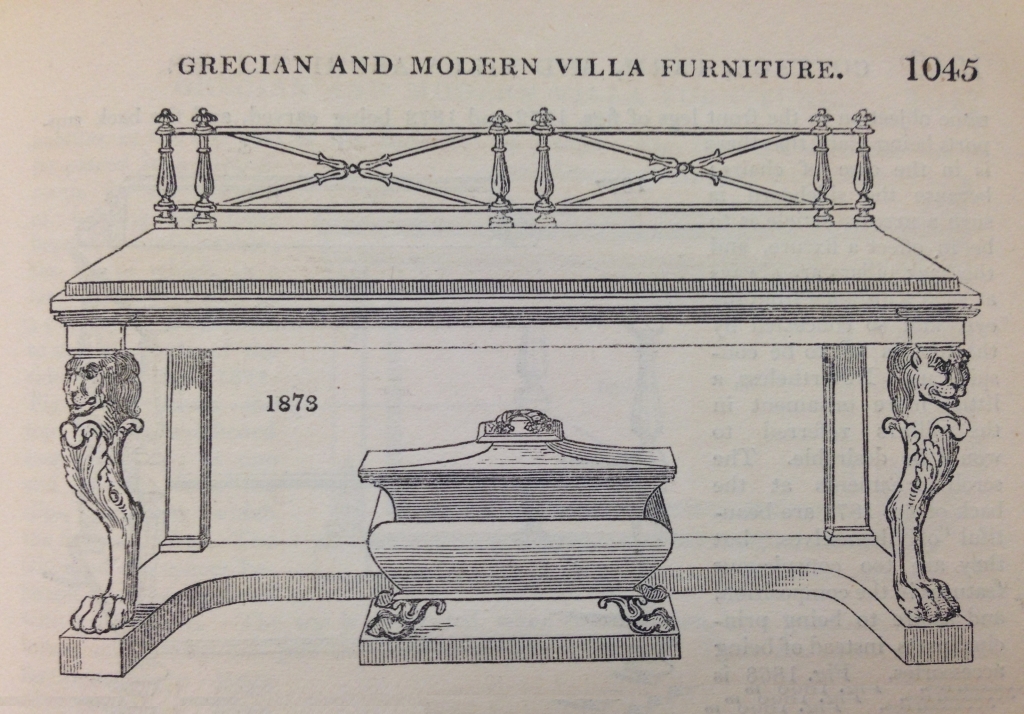

Slightly later, these examples of wine sarcophagi are from John Claudius Loudon’s Encyclopaedia of farm, cottage and villa architecture (1833). The first closely resembles the Elizabeth Bay example:

Sideboard with sarcophagus, Figure 1872 from Loudon’s Encyclopaedia of cottage farm and villa architecture, Longman, Rees, Orme, Brown, Green & Longman, London, 1833. Caroline Simpson Library & Research Collection RB728.370941 LOU

Sideboard with sarcophagus, Figure 1873 from Loudon’s Encyclopaedia of cottage farm and villa architecture, Longman, Rees, Orme, Brown, Green & Longman, London, 1833. Caroline Simpson Library & Research Collection RB728.370941 LOU

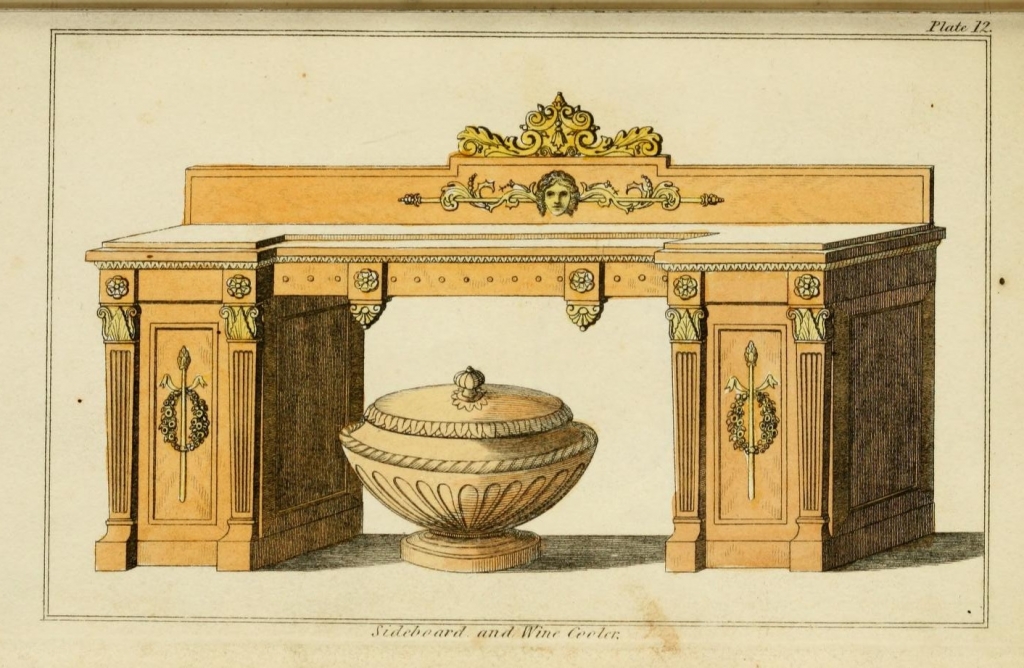

…while this more unusual round design is from Stokes’ ‘The complete cabinet maker, and upholsterer’s guide‘ (London, Dean and Murray, 1829). [3]

Design for a sideboard and round cooler, Plate 12 from The complete cabinet maker, and upholsterer’s guide, Dean and Murray, London, 1829.

A colonial example

The first of Loudon’s designs is similar to this sarcophagus in the dining room at Camden Park, the mansion built by John Macarthur at the Cowpastures, South-west of Sydney:

Red cedar (Toona ciliata) wine sarcophagus in the dining room at Camden Park, open to show the lead-lined interior. Photo © Scott Hill

A rather splendid example from Elizabeth Bay House

The designer of this splendid cellaret, part of the Caroline Simpson collection held at Elizabeth Bay House, has incorporated many neoclassical features, including the heavy-set rectangular shape and pronounced acroteria – the ‘horns’ on the corners that are also seen on James Bicheno’s monument in Hobart. The case is mahogany, while the rams heads and swags are ebonised wood. The fluted feet are seen repeatedly in Piranesi, in examples of urns, boxes and curule chairs. Carved from marble it would sit quite comfortably in a Roman mausoleum! Compare it to the large altar at the right of Labruzzi’s drawing, and this Roman altar in the British Museum, with its rams heads and swag of fruit and leaves:

Roman altar, on each side a floral festoon pendent from ram’s head on the edges. © Trustees of the British Museum 1907,1214.3

This hexagonal cellaret, from the dining room at Vaucluse House is more akin to an angular, banded barrel shape; without its lid it would be called a cistern:

Sideboard and cellaret in the dining room at Vaucluse House. Photo Scott Hill © Sydney Living Museums

Tea and embroidery

Aside from wine bottles, the ‘sarcophagus’ form was commonly used for small boxes such as tea caddies through the late Georgian Regency period and beyond. This is my own tea caddy (though I’ll quietly admit it holds teabags and coffee pods):

…while this small workbox from the drawing room at Elizabeth Bay House and provenanced to Barbara Macleay is also in the recognisable ‘sarcophagus’ form, with a gently curved top and canted sides. The picture on its lid is of the goddess Cybele, seated in her chariot drawn by lions:

Workbox at Elizabeth Bay House. Courtesy Country Threads Magazine © Express Publications Pty Limited

Notes

[1] ‘Esky’ is a generic name in Australia for a portable cooler or ice chest, or in New Zealand and elsewhere a ‘chilly bin’.

[2] Giovanni Battista Piranesi, Le antichità Romane (‘The Roman antiquities’), see for example Book 3, Plate XXVII: Urne, vasi, sarcofagi e oggetti vari ritrovati nelle Camere Sepolcrali precedenti (‘Urns, vases, sarcophagi and various objects found in burial chambers above.)’

[3] You can see the entire The complete cabinet maker, and upholsterer’s guide, embellished with sixteen explanatory and illustrative engravings by J. Stokes, with the articles of furniture elegantly coloured online at the Open Library.

Second helpings

But why ‘sarcophagus’? Isn’t that Egyptian? Though used to describe large Egyptian coffins, it’s actually its a Greek word, which translates as ‘flesh eater’. It was used as a term for a coffin as it referred to the acidic nature of the limestone often used to create ‘coffins’ or ossuaries (to hold bones).

One of the many treasures from the buried towns of Pompeii and Herculaneum are the sheer number of Roman skeletons found by excavators. Because the Romans (especially in Italy) practiced cremation their human remains, and the stories they can reveal to archaeologists of everyday Roman life, are usually lost.

While dating from c. 1815-25, the sarcophagus shown from the Caroline Simpson collection combines elements of the Greek Revival (anthemion motifs) with Roman form and ornamentation associated with the earlier, prominent English architects Robert and James Adam, and furniture maker, Thomas Chippendale. There is a marked similarity to an actual cinerary box from the collection of William Weddell of Newby Hall, Yorkshire. Robert Adam created a sculpture gallery (1767) for Weddell (he had acquired pieces from, amongst others, Piranesi) and arranged the collection. Rams heads are a strong motif in that collection and Adam used these linked with delicate swags as a motif on the plinths he designed for the hall. Adam had earlier used this ram-headed and swagged cinerary form, probably after Piranesi, in a design for a Grotto for Lord Scarsdale (Harris, p84). Depending on whether the piece is close in date to Thomas Hope’s Household furniture & interior decoration (London, 1807) or George Smith’s The cabinet-maker and upholsterer’s guide (London, 1826) (the Bramah patent lock suggests the latter), there may be an element of historical revivalism to the piece (i.e. of decoration associated with Chippendale such as the corner-mounted rams heads, linked by laurel swags). [excerpt: accession notes for the sarcophagus]

You can read earlier posts about ice in the colony here and ice chests at Rouse Hill House here.