‘Gunpowder, caper and twanky’ – what on earth were the Macarthurs drinking? With Vintage Sundays: Regency taking place this Sunday at Elizabeth Farm, we thought we’d have a taste of tea varieties that were popular in the 1810s and 20s.

If we could persuade ourselves to live together as shepherds, and be contented with bread, milk, meat and vegetables, and the variety of fruits that are raised to perfection in this climate it would be all very well. But then we must have a number of imported luxuries…

Elizabeth Macarthur, writing from Parramatta, to her friend Bridget Kingdon in Bridgerule, Devon, Sept 21, 1822

Foremost among those luxuries was tea.

In June 1805 John Macarthur returned to Sydney from London, accompanied by sheep and the paperwork that would secure him the land that would become Camden Park. He brought with him Miss Penelope Lucas, who had been caring for his young daughter Elizabeth, and who would become Governess to all his daughters.

While Penelope Lucas initially lived with the family at Elizabeth Farm, she is more closely identified with a small house located a few hundred meters to the north west of the house: Hambledon Cottage, built 1821-22 as the second residence of the Macarthurs’ Parramatta estate. The original clear vista to the cottage from the main house is long built out, but the tall bunya and hoop pines beside it can still be seen above the rooftops. It was built to provide badly needed extra accommodation and, from 1827 until her death in 1836, became the residence for Mrs Lucas; although unmarried, the honorific ‘Mrs’ now attached to her name meant that Penelope Lucas could house unmarried men under her own roof without any social awkwardness or raised eyebrows. Each day she would take the short walk up to the main house to take tea with Elizabeth and meals with the family.

But what type of tea did they enjoy?

Teas – green, black, and blended

Individual tea blends such as those enjoyed by Elizabeth and Penelope were a very personal taste and also a matter of social standing and display. Selections of black and green teas were often blended from teas kept in caddies or their larger freestanding version, the ‘tea puoy’.

In Elizabeth Gaskell’s 1851 novel Cranford the character Miss Matty opens a tea shop but has to be persuaded to keep selling green tea, which she believed was ‘[a] slow poison, sure to destroy the nerves, and produce all manner of evil’. Cranford‘s narrator also notes that ‘… expensive tea is a a very favourite luxury with well to do tradespeople and rich farmers’ wives, who turn up their noses at the Conjou and Souchong prevalent at many tables of gentility, and will have nothing else than Gunpowder and Pekoe for themselves’. It’s an opinion also seen in contemporary texts that state the most sought after teas were usually the ones with the highest price – a fact not lost on retailers.

Black tea, created by curing or smoking tea leaves, was popular among traders exporting from China as it was hardier for a long voyage than the dried ‘green’ teas. Of the teas available from Miss Matty’s shop, ‘conjou’ is a black tea, and is one of the leaves used in making the ‘English breakfast’ blend. ‘Souchong’ is also a black tea variety that includes the familiar lapsang souchong, a smoked tea. ‘Pekoe’ is made from very young, unfurled leaves, and was considered a high quality green tea. The intriguingly named ‘gunpowder tea’ is a strong, green Chinese tea, most likely named for its tightly rolled pellets resembling gunpowder, and which expanded in hot water. All of these were served and blended at colonial tables.

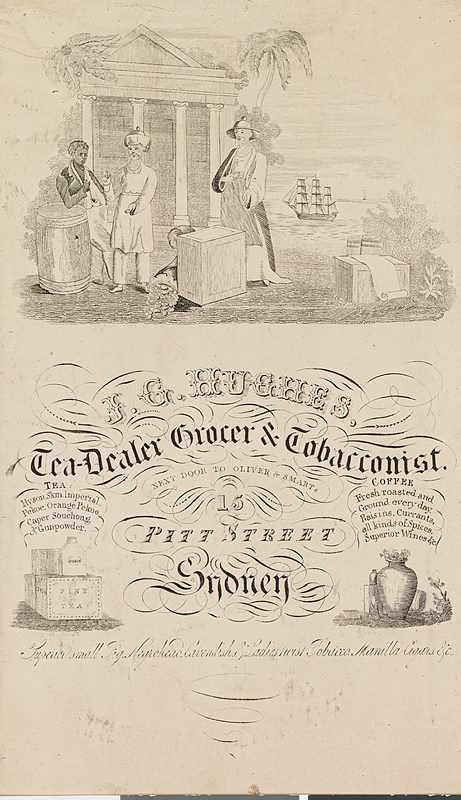

Bill head, J. G. Hughes Tea Dealer, Grocer & Tobacconist, William Moffitt, ca. 1836-1880. Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW: PXA 368

Listed in this advertisement (above) for ‘J G Hughes: Tea Dealer, Grocer and Tobacconist’, (coffee roasted fresh daily!) – whose shop was on Pitt Street in Sydney, you can see hyson skin (a green tea, though inferior to the young twisted leaves of hyson tea), imperial (a hyson, and as the name suggests, a very high quality tea) , pekoe and orange pekoe (a tea named for the Dutch House of Orange), caper, souchong and gunpowder.

‘Caper’ tea? This was a tea characterised by the leaves being ‘cemented’ together by a vegetable gum into a ball shape, presumably resembling a caper flower. Like souchong, it was a tea that took longer to draw. The fabulously named Tsiology; A discourse on tea: being an account of that exotic; botanical, chymical, commercial, & medical, with notices of its adulteration, the means of detection, with a brief history of the East India Company (you have to love 19th century book titles!) published in London, 1826, by ‘A Tea Dealer’, notes that, while once a very superior tea, caper had of late been of such a poor quality that ‘a great quantity were being withdrawn almost every sale and sunk (or drowned as the term is) at Gravesend, as unfit for consumption’. In other words it was thrown overboard. The shoreline at Gravesend must have been an interesting colour…

The author also wrote that while shopkeepers were selling tea under a myriad of fanciful names, the East India Company imported them only under the names bohea (the lowest quality tea), congou (its better variation), souchong (including ‘Campoi, Tetesung and Padra’), pekoe (all black teas), and caper, along with the green teas twankay and hyson (‘including young Hyson and Gunpowder’).

Elizabeth Macarthur’s letter – that started this ramble into tea-dom – has an interesting twist. She complains to Miss Kingdon that well-trained servants were a scarce commodity for well-to-do colonial families such as theirs. In a seller’s market the would-be staff were able to make higher demands for wages and perks, and life’s little luxuries became a bargaining point: ‘Even our servants will have tea, sugar and other things, which many of them have never in their former lives been accustomed to indulge in.’

The provisioning of tea for their staff by the Macarthurs and families like them actually became a standard by 1825, when a daily ration was even officially allocated for convicts (the quality of the leaf can be surmised). This was however a discretionary article – quickly withdrawn in the event of poor behaviour.

Tea today?

If you’re visiting Elizabeth Farm, the Tearooms are open Saturday and Sunday, from 10:30 am till 3pm, serving light lunches, cakes and treats – all made on site. Why not stop by to take tea, just as Penelope Lucas would have done all those years ago? And to really throw yourself into all things Regency don your bonnet and tie your jabot and head out to our first Vintage Sunday: Regency this Sunday, from 11am till 4pm.

Tea-time treats

At a recent Afternoon at the Macarthurs‘ HHT Members were treated to a Regency tasting experience including a variety of teas similar to those available in the early colony. Along with the various blends, Jacqui Newling (The Cook) and long-term Elizabeth Farm guide, Jacky Dalton, prepared a selection of sweet treats. These were based on popular Regency recipes, reflecting a taste for sugar and spices: ginger bread, plum cake and rout cakes with caraway seeds and rosewater were offered, but I have to say the stand out was the Lemon Cheesecakes.

Lemon cheesecakes

Ingredients

- 2 large lemons

- 110g white sugar

- 6 egg yolks (keep whites for another use)

- 225g unsalted butter

- 425g fresh ricotta cheese (or other light curd cheese)

- 490g frozen puff pastry (thawed)

Note

The original recipe that inspired these cheesecakes is from The art of cookery made plain and easy by Hannah Glasse (1796). Contemporary author Kim Wilson modernised the ingredients and measurements, and included the recipe in her delightful book Tea with Jane Austen (Frances Lincoln Publishers, 2011). Apparently these were a favourite treat of Jane Austen's niece and nephew, Fanny and Edward. But be warned, they veritably ooze with butter!

Makes about 24 muffin-sized cheesecakes, or 48 mini muffin-sized, as served for afternoon tea. If using smaller muffin tins, baking times will be reduced.

Directions

| Preheat oven to 180 °C. | |

| Peel the lemons, then cut the peel into small chunks. Boil gently, in enough water to cover the peel sufficiently without boiling it dry, for about 45 minutes or until very tender (use a non-reactive pan such as stainless steel). Drain. | |

| In a food processor, process the lemon peel and sugar until finely ground. Add the egg yolks, butter and ricotta, and process until well blended. | |

| Cut the pastry into circles big enough to line the bottom and sides of the muffin holes, and press into the tins. | |

| Spoon the cheese mixture into the pastry shells, filling each three-quarters full. | |

| Bake for approximately 30–40 minutes, or until the cheesecakes are puffed and golden, and a knife inserted into the centre comes out clean. Chill before serving. | |

Print recipe

Print recipe