In your local greengrocer it’s hard not to find a stack of pineapples, and this isn’t including tinned slices or juice. Far from being the luxury item of the early 1800s, they’re now available everyday.

You have to wonder exactly what they were expecting, but visitors and newcomers to New South Wales were often astonished by the fruits and vegetables that grew in colonial gardens. Accustomed to seeing some fruits grown only in costly hothouses, or as expensive imports, if at all, seeing exotic specimens growing in the open quickly reminded people that they weren’t in Britain anymore.

In 1837, James Macarthur summed up the possibilities in his New South Wales; Its present state and future prospects (London : S. Walker, 1837). Though a little rose tinted, it must have presented a tempting picture to his British readers:

The climate is proverbially mild and salubrious; the soil productive, yielding every grain and vegetable useful to man, with fruit in the highest perfection, and of all varieties, from the currant and gooseberry of colder climes to the banana and the pine-apple of the tropics.

18 years earlier William Charles Wentworth (1793-1872) had published his Statistical, historical, and political description of the colony of New South Wales (London: G. & W.B. Whittaker, 1819). This was one of several ‘improving’ guides available that provided a description of the colony both for the curious ‘back home’ and for the new settler (willing or unwilling). Following his own observations on the drawbacks of the convict system and for the general advancement of the colony, Wentworth gave a lengthy section on kitchen gardens, outlining what to expect from the weather, soil conditions and tips for cultivation of specific crops. By mentioning ‘gentlemen’, he places pineapples as a fruit to be considered by the colony’s upper classes, who had the means and the land to dedicate to their production. Reading between the lines, Wentworth is pointing out that New South Wales was not merely a prison colony.

In the management of Pinery, should gentlemen incline their attention thitherward, the following observances will be useful. In May let them be unplunged [i.e. removed from the manure pile unpotted], and laid down on their sides, till all their leaves be free from water. Take off all yellow leaves, and suckers, and let these suckers be plunged into fresh pots of earth, and in a fresh bed of heat, by means whereof the Pinery will always be kept full. The spider [the red spider mite, bane of many a fruit grower] is their chief enemy and therefore should not be permitted to harbour near them, as the smallest of the tribe will kill the crown’ and destroy the fruit.

The key to the basic method Wentworth describes – a ‘bed of heat’ – was a pile of decomposing vegetable matter such as manure or tanner’s bark which generated the extra heat the pineapples required to fruit to a large size. This had been the standard method of heating ‘pinerys’, structures dedicated to pineapple production, for a century. If you’ve ever seen a full compost heap steaming with its inner heat on a midwinter morning you’ll understand just how much heat these heaps can produce. The pineapple pots were variously placed above the heap, or plunged into it, taking advantage of the ‘bottom heat’ that was widely advocated. Skilled gardeners would carefully regulate the temperatures by airing the pinery, turning the heap or airing it with pipes. This technique, which was exhaustively discussed in journals, magazines and books, was soon replaced by piped steam or hot water, the same way that many 19th century orchid houses were heated. The remains of a splendid series of steam-heated hothouses, used by Sir William Macarthur for tropical plants including his orchid collection, can be seen at Camden Park, an hour south-west of Sydney.

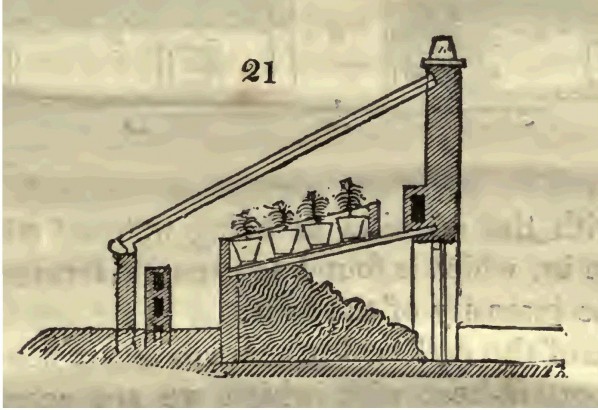

A bottom-heated pinery, from J C Loudon’s Different modes of raising the pineapple, London, 1822, fig21: ‘The method of Mr Thomas Jenkins of Portman Nursery, London,’ Source: Open Library http://archive.org/details/differentmodesof00loudrich

We see variations of these methods in designs published by the Scottish theorist on ‘pretty-much-everything’, John Claudius Loudon (1783 – 1843). In this illustration (below) from his 1822 ‘The different modes of raising the pineapple’, terraced rows of pots are warmed by heat-generating manure and tanning bark heaped underneath them. Leading growers, he noted, were already experimenting with techniques apart from the standard ‘plunging’ method. Loudon also mentions that pineapples from the Caribbean were imported to London in summer, after a six week voyage: “moderate sized fruit may be had from half a crown to a crown each, or at 2 shillings a pound”. It would be some time yet before pineapples were imported to Sydney, though the preserved fruit and ‘pineapple rum’ appeared quite early in newspaper advertisements. The very 1970s sounding ‘pineapple cheese’ that was also heavily advertised in the 1820s was actually a type of cheddar, named not for its fruity content but for its distinctive criss-cross markings.