Along with 6 generations-worth of furniture, paintings, clothing and ephemera, Rouse Hill House is crammed with a rich collection of kitchenalia. Routine housekeeping of the house’s service wing provides a great opportunity to see these objects up close.

Housekeeping at Rouse Hill House is never a straight forward affair. An everyday vacuum cleaner would shred the original carpets, and the fragility of many objects means cotton buds and soft brushes are the curators’ ‘weapons of choice’. ‘Deep cleaning’, which involves removing and individually cleaning every object might only take place once every year.

Mel Flyte and Jane Beeke engaged in the careful art of museum housekeeping at Rouse Hill House. Photo (c) Scott Hill for Sydney Living Museums

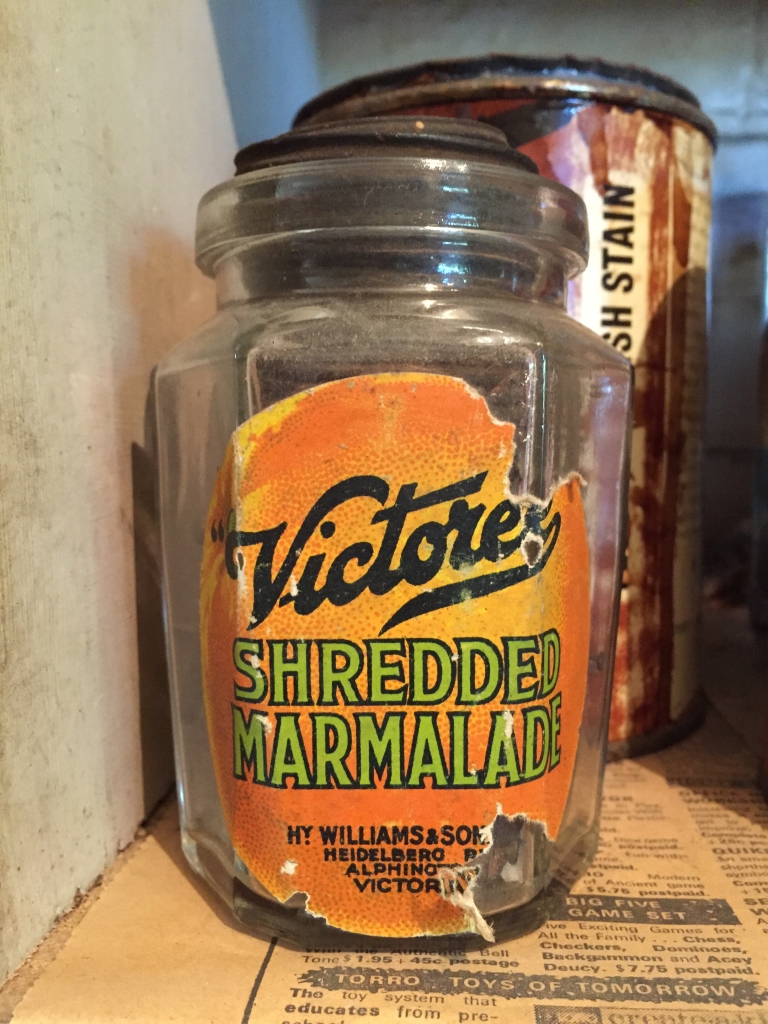

Deep cleaning a space like the storeroom – one of the 7 rooms in the house’s main service wing – is therefore a large undertaking, and one which takes several days. Located alongside the kitchen and scullery , the narrow-proportioned room’s large central fireplace – ostensibly far too large for the space but clearly not utilitarian – indicates it was originally created as a housekeeper’s or servants’ sitting room. Today it’s a crowded, eclectic space full of jars, stacks of plates, lamp parts, tea sets, magazines, pieces of broken furniture and ‘somethings’, welding rods (yes, you read that correctly) and gramophone records. The framed photograph of the ‘hunt lunch’ also sits here, along with the spare table leaves from the dining room.

Plan of the ground floor of Rouse Hill House showing the storeroom in the rear service wing

Assistant curator Jane Beeke in the storeroom at Rouse Hill House. Photo (c) Scott Hill for Sydney Living Museums

This week Mel Flyte and Jane Beeke from our curatorial team have been tackling this complex room. As the procession of material went in and out to the work tables set up in the arcade, dining ware, kitchenalia, old Arnotts’ biscuit boxes and soda siphons all fought for our attention. It highlights a fundamental aspect of the Rouse Hill collection: that every aspect of life in the house is preserved, and the ephemera which is usually the most vulnerable to loss is instead to be found everywhere. A sackful (literally a hessian sack of 30 tins!) of degraded tins of corn raised a whole other issue – how to preserve a collection that includes foodstuffs!

Soda siphons, lamps and jam jars in the storeroom at Rouse Hill House. Photo (c) Scott Hill for Sydney Living Museums

Arnotts ‘Famous thin Captain’ biscuit box in the Rouse Hill House storeroom. Photo (c) Scott Hill for Sydney Living Museums

‘Fresco flaked rice’ tin in the Rouse Hill House storeroom. Photo (c) Scott Hill for Sydney Living Museums

A stack of side dishes in the storeroom at Rouse Hill House. Photo (c) Scott Hill for Sydney Living Museums

Japanese tea set in the Rouse Hill House storeroom. Photo (c) Scott Hill for Sydney Living Museums

Everyday jam jars

Three objects especially caught my eye, that tell a story of domestic life over multiple generations: everyday jam jars.

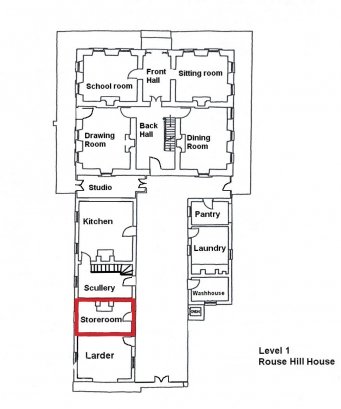

The strawberry jam jar in the opening photograph and that was served on the Rouse’s breakfast table came all the way from Britain, made by the 1822-founded company Moir and Son. This was a company significant in the history of canned and preserved foods, and well-known for their Seville orange marmalade:

John Moir & Son Ltd. was a pioneer in the manufacturing of preserved foods. The business was established in Aberdeen in 1822 when it was the first company to introduce preserved food products in the UK. The firm began by preserving salmon for export and subsequently added meats, soups, game and vegetables. Trade was slow for a time as public prejudice had to be overcome and a market had to be created. Once the preservation methods adopted by John Moir & Son had been proved, a demand in the UK and overseas sprang up and the company expanded to become the largest of its kind in the country, with offices in London and extensive connections with India, China and Australia.

In 1880 the company was incorporated as John Moir & Son Limited. By the end of the 19th century the business had introduced condensed milk, marmalade, jams, jelly powder, and baking powder to its product range. [1]

The jar features accolades and that great seal of approval, that they were purveyors to the Royal Household. It may not have been the Queen, but supplying the Prince of Wales with his jam wasn’t a bad ostrich feather in their cap (pun intended).

Side labels from a Moirs jam jar at Rouse Hill House. Photo (c) Scott Hill for Sydney Living Museums

Other jars in the storeroom match the Moir jar, albeit scrubbed clean of their labels, and indicate the well-made jars were being recycled, possibly for home-made jams. This jar was bought at a time when there was a general store at the local Rouse Hill village, but household provisions for the ‘house on the hill’ were likely ordered in bulk and delivered, augmenting home-grown produce.

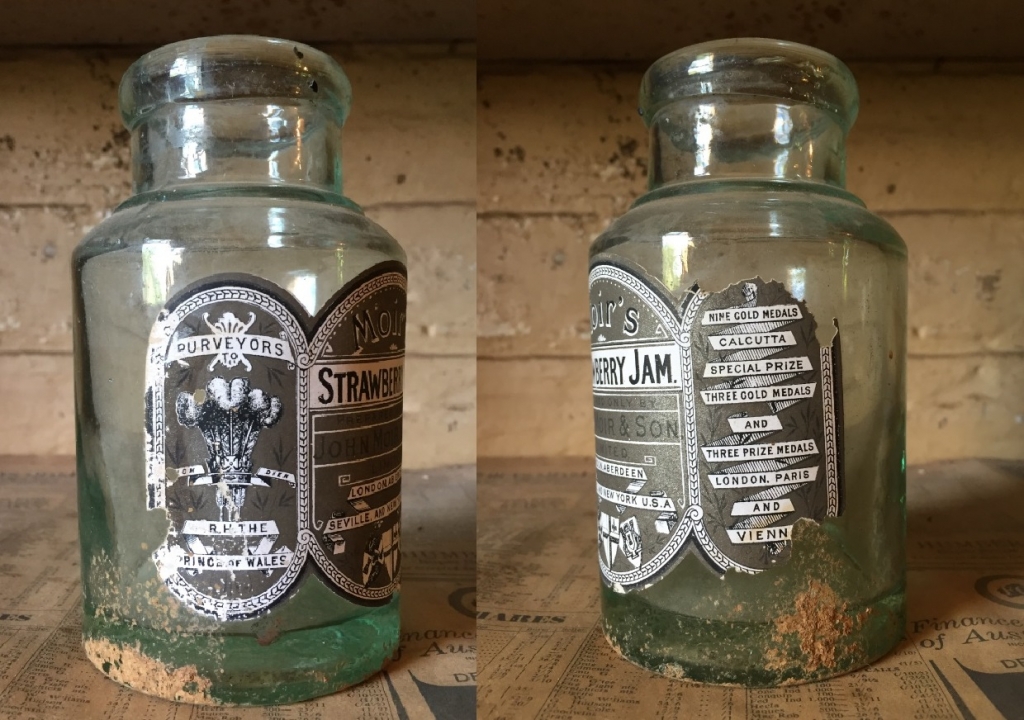

Jump forward about 50 years and a second jar, emblazoned with a colourful, cheery orange, is now a local Australian brand – “Victoree”, manufactured in Victoria. The marmalade from this jar may have been enjoyed by Nina Terry and her husband George. In the late 1940s Victoree’s advertising aimed at shifting approval from home-made to bought marmalade, and carried the pithy slogans:”Wise housewives don’t make marmalade now “VICTOREE” Marmalade is PERFECT!” and “A good appetiser! Victoree marmalade on toast!“. I don’t know about you but I’m rushing out to buy some!

‘Victoree’ brand marmalade jar. Rouse Hill House collection, photo (c) Scott Hill for Sydney Living Museums

The third jar, of IXL apricot conserve seen here alongside the earlier Moir’s, is another Australian-made brand (originally founded in Hobart by Henry Jones in 1891) and epitomizes the triumph of the supermarket and consumerism. Rouse Hill House was no longer a rural property but close to supermarkets and stores, where this jar was bought. This jar dates to the period of Rouse Hill’s last permanent occupant, Nina’s 4th son Gerald Terry, the last person to cook in the kitchen at Rouse Hill.

Jam jars in the Rouse Hill House storeroom. Photo (c) Scott Hill for Sydney Living Museums

Notes

[1] A brief history of the Moir & Son company by Michael Behm from COSGB – A blog for the Commercial Overprint Society of Great Britain (COSGB). Sunday, March 17, 2013

Another great post on Moir & Son, and their Seville orange marmalade, is Dr Kirsty Hooper’s “Oranges *are* the only fruit: John Moir & Sons (Aberdeen, London & Seville) and the re-Hispanicizing of Marmalade” from the blog Hispanic Britain, or, An Anglo-Spanish Miscellany – Interesting bits and bobs from my research into the connections between Britain and Spain during the long nineteenth century,