The ancient Egyptians valued watermelons so highly that they entombed Tutankhamen with a stash of them. In colonial NSW, that sweet ruby flesh was hardly less prized – as a story from the early years of Vaucluse estate goes to show.

Bags, bludgeons and a quantity of Water-Mellons

As the summer of 1811 drew to a close, Sir Henry Browne Hayes, the roguish convict owner of Vaucluse estate, put a notice in the Sydney Gazette offering a reward of 10 guineas to

any Person that will give Information so as to prosecute to Conviction the Person or Persons, who on Tuesday and Wednesday night last robbed my Garden, at Vaucluse, of a quantity of Water-Mellons; and on Thursday being fired at, left Bags and Bludgeons behind.[1]

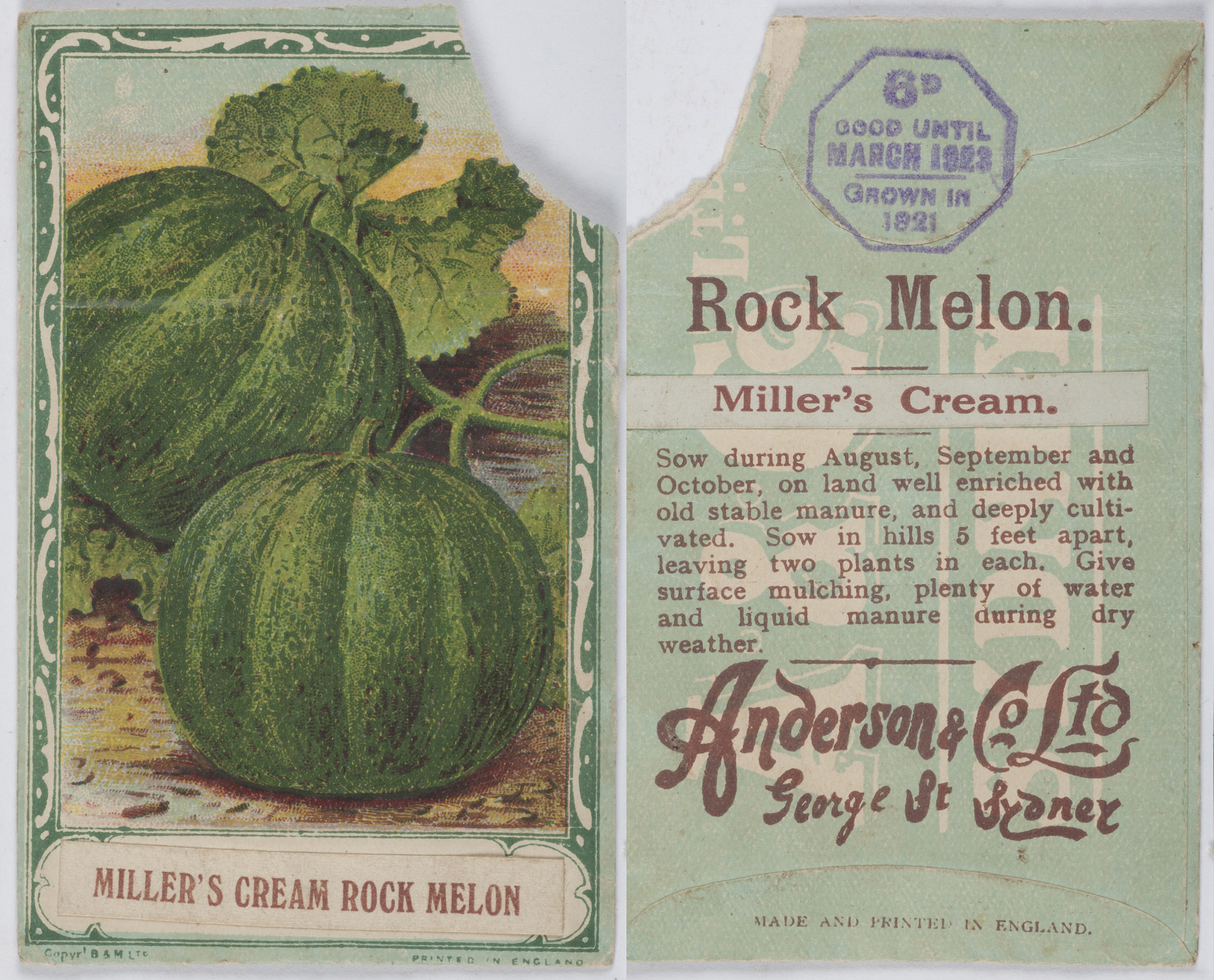

Melons have a particularly close association with Vaucluse House – and not just because of the infamous episode with the bludgeons. William Charles Wentworth, who remodelled the house and grounds from the 1820s, was said by his wife, Sarah, to be fond of ‘a good mellon’– so fond, in fact, that in 1843, he entered a rock melon in Sydney’s horticultural show.

The Cook, Jacqui Newling, has also unearthed references to melons for sale, presumably from the kitchen garden at Vaucluse, in the Wentworths’ accounts books.

Horticulturist Anita Rayner holds a jam melon, an important Victorian crop, in the kitchen garden at Vaucluse House. Photo © James Horan for Sydney Living Museums

A cooling treat

If nothing beats the heat quite like a slice of juicy watermelon, this was especially so in the era before Paddle Pops. Ice did not arrive in the colony until 1839 (nearly half of it melted en route from Boston). So when temperatures soared, melons – picked from the vine early in the morning, or taken from a cool pantry or cellar – were a favourite way of cooling off.

Here’s Louisa-Anne Meredith, an English-born author and illustrator, describing a popular method of preparing watermelon in 1844:

One approved method of eating it is, after cutting a sufficiently large hole, to pour in a bottle of Madeira or sherry, and mix it with the cold watery pulp. These melons grow to an enormous size (an ordinary one is from twelve to eighteen inches in diameter), and may be seen piled up like huge cannonballs at all the fruit-shop doors, being universally admired in this hot, thirsty climate.[3]

Monster melons

Lousia-Anne wasn’t the only one to marvel at the epic proportions of NSW’s melons.

Just eight months after the first melon seeds arrived in NSW with the First Fleet, melons were thriving in Governor Phillip’s garden. In March 1791, a young Elizabeth Macarthur, the future matriarch of Elizabeth Farm, gave a vivid account of enjoying one of these melons at his table:

We have also very fine melons. They are raised with little or no trouble, the sun being sufficient to ripen them without any forcing whatever, and bringing them to a great size and flavour. One day after the cloth was moved, when I happened to dine at Government House, a melon was produced weighing 30 lbs.[4]

Elizabeth’s talk of ‘forcing’ has a special horticultural sense. In England and continental Europe, melons were ‘forced’ to ripeness in special ‘frames’, made of glass and brick. But to the astonishment of early colonists, they grew more or less unaided in NSW.

In his advice to aspiring colonists, William Charles – a published author as well as a melon aficionado – reported that ‘melons of all sorts, attain the highest degree of maturity in the open air’.[5] Indeed, the melons were so plentiful at Elizabeth Farm that they were used to feed the pigs.

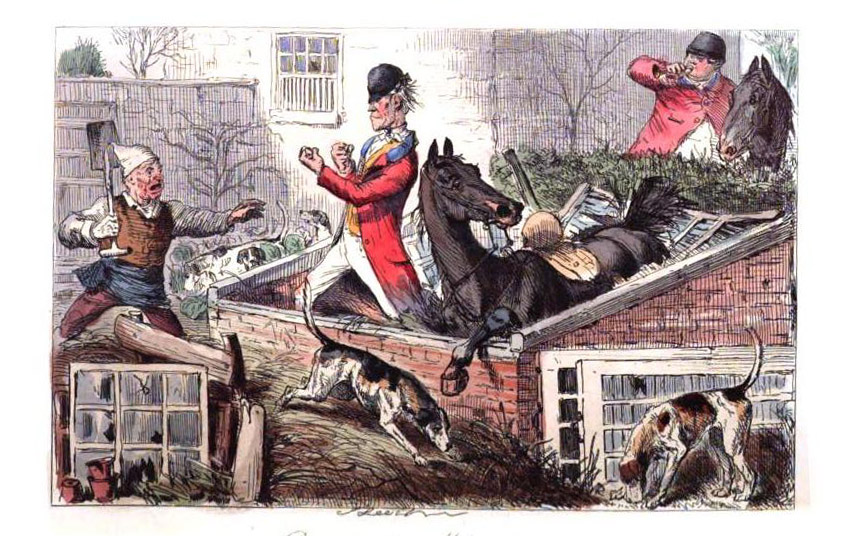

This coloured plate, ‘Pigg in the Melon Frame’, by illustrator John Leech, illustrates a typical Victorian melon frame. It appears in Handley Cross, an 1854 satirical novel by Robert Smith Surtees.

The melon hustlers

The great Vaucluse melon heist of 1811 wins points for audacity: the thieves landed at Vaucluse Bay and rowed (or sailed) triumphantly back to Sydney, minus bags and bludgeons, but in possession of a boatful of melons. But this was by no means an isolated incident.

At the same time as Elizabeth was enjoying her melon at the Governor’s table, Sydney’s fledgling vegetable gardens were at the mercy of plundering convicts and marines. The larceny was so bad that Lieutenant Ralph Clark established his plot on the tiny islet off Darling Point (now Clark Island). ‘I thought that having a Garden on an island it would be more Secure,’ he lamented, ‘but I find that they even get at it.’[6] (You can read more in Jacqui’s book, Eat Your History.)

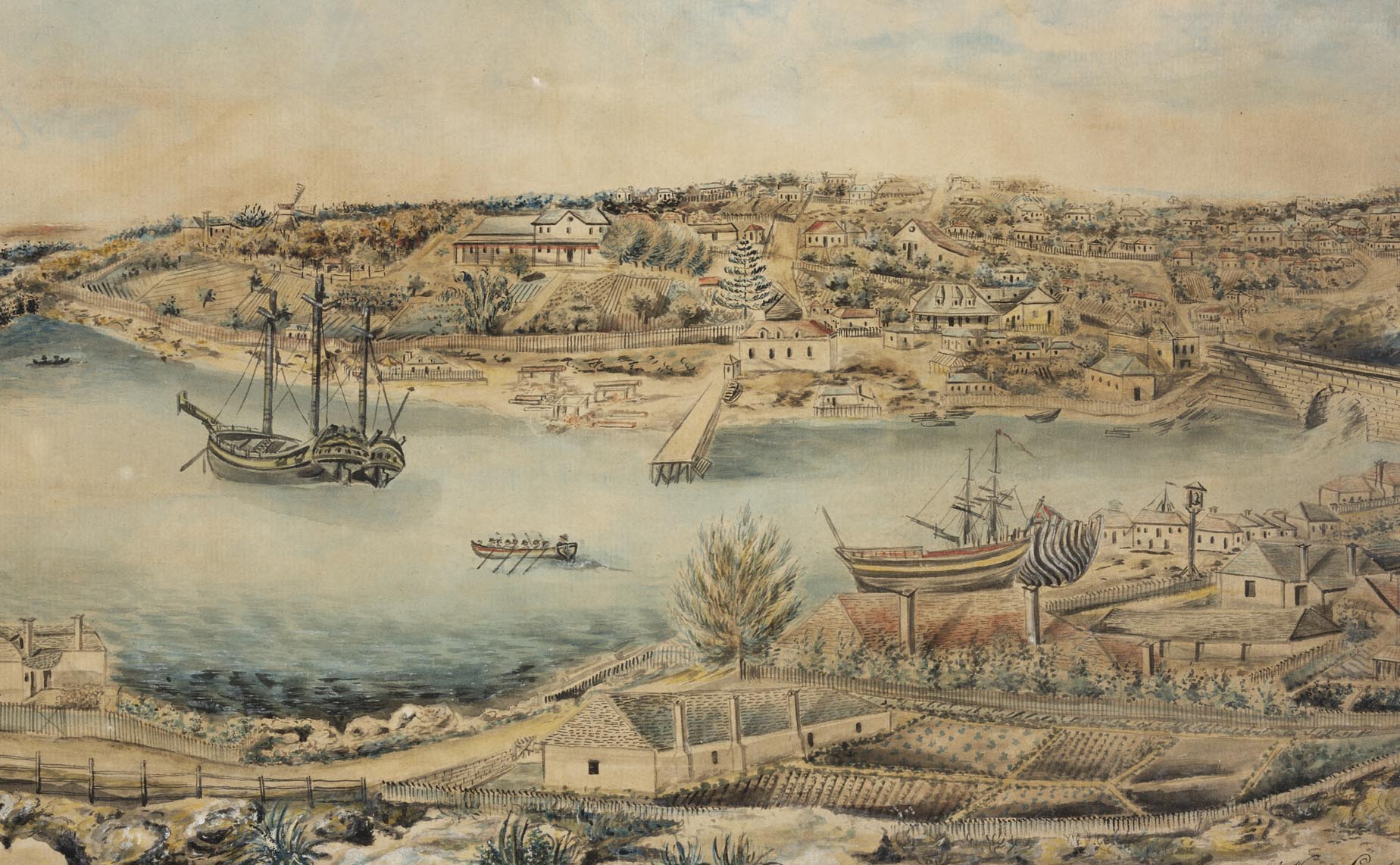

Sydney’s fledgling gardens, depicted in this c.1803 watercolour by John William Lancashire, were at the mercy of plundering convicts and marines. View of Sydney Port Jackson, New South Wales (detail), Dixson Galleries, State Library of NSW DG SV1 / 60

Every melon season, NSW newspapers filled with reports of melon stealing, particularly from the market gardens of Richmond and Penrith. A range of motivations, from hi-jinks to genuine hunger, were probably at play.

Profiteering was also suspected in many cases. Trucks lumbering fully laden to market were liberated unknowing of their load; gardeners watched over their ripening crops with firearms at the ready. (Many met their mark: shot injuries were not uncommon among the apprehended.) An 1891 report in the Windsor and Richmond Gazette went so far as to refer to a melon-stealing ‘industry’.[7] And throughout the 1910s, the annual Nepean Show featured a melon-stealing race on horseback.

Sweet justice

So Sir Henry was by no means the only target of melon theft. But the serial trouble-maker had particularly good reason to wish to protect his crop. In 1810 – the year before the great Vaucluse watermelon robbery – he had been brought before the bench for endeavouring to raise a riot. ‘I reprimanded & discharged him,’ the judge noted, ‘since which he has sent me two Water Melons each week, of uncommon size and goodness.’[8]

No doubt the melons sweetened the deal.

—Guest blogger Helen Curran is an assistant curator at Sydney Living Museums

A 1920s seed packet from a Sydney nursery for Miller’s Cream rock melons. Caroline Simpson Library & Research Collection

[1] Sydney Gazette, 9 February 1811, p. 2.

[2] Sarah Wentworth to Thomasine Fisher, 20 December 1861, ML A868, p. 115.

[3] Louisa-Anne Meredith, Notes and sketches of New South Wales, London: John Murray, 1844, p. 43.

[4] Sibella Macarthur Onslow ed., Some early records of the Macarthurs of Camden, Sydney: Angus & Robertson Ltd, 1914.

[5] William Charles Wentworth, A statistical, historical, and political description of the colony of New South Wales, London: G. & W. B. Whittaker, 1819, p. 94.

[6] Jacqui Newling, Eat your history, Historic Houses Trust of NSW, p. 70.

[7] Windsor and Richmond Gazette, 21 February 1891, p. 4.

[8] Ellis Bent, Letterbook, 1809–11, NLA, Ms 195 quoted in Yvonne Cramer, This beauteous, wicked place: letters and journals of John Grant, gentleman convict, Canberra: NLA, 2000, p. 98.