How ‘traditional’ does something have to be before it becomes tradition? High tea, as an entity, has been around for over 150 years, but the ‘traditional high tea’ that we enjoy today, with delicate sweet and savoury morsels, bears little resemblance to high teas 100 or even 50 years ago: it was a meal, usually taken in the evening. Again, we turn to Mrs Beeton for authority on the matter:

Tea as a meal, or more often, an apology for one, is one of the most useful of all as an easy form of entertainment …

She concedes however:

High tea may be a meal, it being really worthy to come under the category. It can be served more easily in small households, where service is lacking, than dinner or luncheon. It is specially convenient in the summer, when out-of-door amusements are going on, and guests may be bidden to one without formality. Mrs Beeton’s All about cookery 1902.

Tea party in front of wisteria, photograph taken at Vaucluse House around 1912, from Nielsen-Vaucluse Park Trust photograph album, no.2. Caroline Simpson Library & Research Collection, Sydney Living Museums NVPT album no.2

No apologies necessary

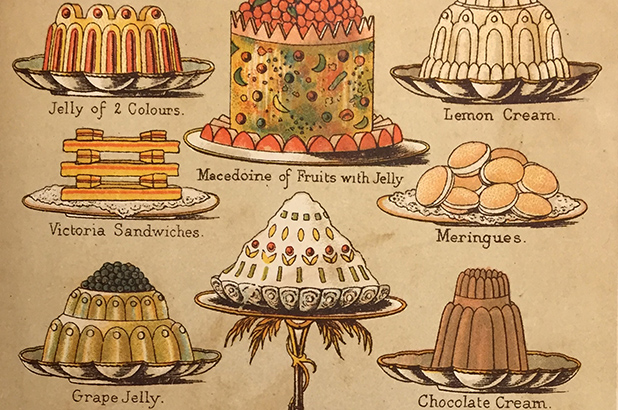

Rather than a selection of finger foods served in the afternoon, high teas were in essence, a fairly substantial evening meal – or a supper, perhaps – hosted without the strictures of a formal meal. Even in ‘households where service is lacking’ they still involved several dishes and quite a bit of preparation.Beeton’s summer high tea menu comprised Mayonnaise of salmon; cold chicken, tongue; galantine of veal; salad; cucumber; Fruit compote; jelly; pound cake’ strawberries and cream; tea, coffee etc. In winter, the more robust Fish rissoles; mutton cutlets; cold game; hashed turkey; sponge cake pudding; lemon cream; madeira cake; stewed prunes and tea, coffee etc. These selections were lighter than those recommended in Sydney by cookery teacher Harriet Wicken in the 1890s who taught her pupils to prepare fricassee of rabbit, fish cutlets, snapper and potatoes, mullet and piquant sauce, and fricassee of lobster and prawns for a High Tea. (‘A high tea’, Evening News (Sydney NSW: 1869-1931), Thursday 17 May 1894, p2).

No more ‘crushing and sandwiching’

High teas were not just for the domestic entertainer, they were also given at respectable establishments such as David Jones in the 1930s, and at community functions, as this extract from The Bathurst Times, Thursday 25 June 1914 explains:

The people of Bathurst will to-night have the opportunity of experiencing the pleasures of a high -tea. The’ Ladies’ Guild of All Saints’ Cathedral have undertaken the tremendous task of catering for about 500 people or more at the Masonic Hall. The high tea has superseded the ancient and much honored tea meeting, with its -first, second, and third sittings, and its attendant, crushing and sandwiching, and people now have, the courses of a meal served in a sober and dignified manner. The tea will commence at 6 o’clock.

Not so high but by no means low

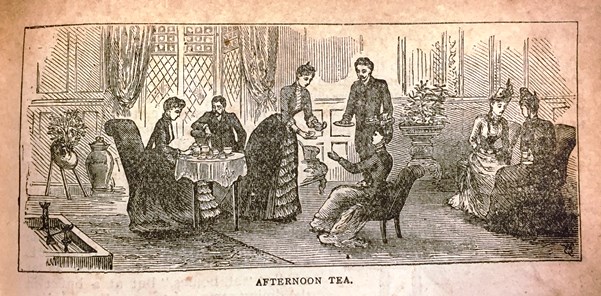

Afternoon tea in Mrs Isabella Beeton, Mrs Beeton’s book of household management, Ward, Lock & Co, London, circa 1880. Sydney Living Museums R89/80

Except for the three tiered presentation stands that have become a standard feature of high teas today, especially in commercial venues, the ‘classic’ or ‘traditional’ high tea, is more closely related to dare I say, ‘plain old’ afternoon tea, which in Mrs Lance Rawson, The Antipodean cookery book and kitchen companion, George Robertson & Co, Melbourne, 1895, p450

Serve rolled bread and butter, sandwiches made of ham paste, potted ham, tongue, or chicken. The crust of the bread should be cut off, and the sandwiches cut into three-corner shapes of fingers. Anchovy sandwiches, or those made with cheese paste, are liked by gentlemen.

Salads are allowable nowadays at afternoon teas; egg, oyster, or chicken, are suitable with brown bread and biscuits.

Cakes for this purpose should be very small.

Wine and cordial should always be on the sideboard; claret cup or champagne on the table.

The addition of champagne certainly takes it away for the ‘plain old’ – in the late 1800s and well into the 1900s, ‘afternoon tea’ had as much cache as ‘traditional high tea’ does today. It seems that for modern generations the term ‘high’ is necessary to raise the image from an afternoon tea, which we could take on any chosen day, to take on the meaning of high-brow, high-end or high-class.