Here at the Cook and the Curator conversations often have a circuitous feel to them. This week a chat about Mrs Rawson’s 1879 Queensland Cookery Book and recipes for stewed bandicoot (to the incredulous horror of our colleagues who were listening in) ended up with the taxidermed trophies in the front hall at Rouse Hill House – and the broader topic hunting in the 19th century.

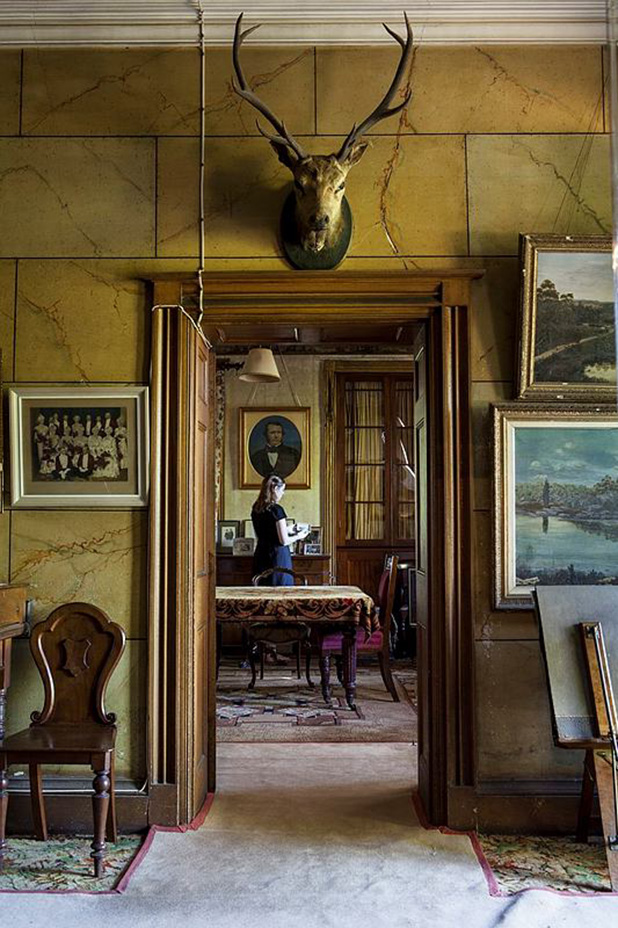

Visitors to Rouse Hill House are greeted by three stag heads, placed above the doorways. They sit above a framed photograph of the Sydney Hunt Club, taken at a meet held at Rouse Hill House. While not actually the trophies of a hunt held in Australia (although deer had been imported many years earlier), they do represent the importance and every day reality of hunting to families like the Rouses and Terrys – even if by 1900 it had assumed a role far more important for its social symbolism. When you read colonial accounts, it seems that in almost every chapter something is getting blasted out of the air, bush or water: a flock of parrots is first admired, then served in a pie.

Tally ho!

In 1847 Godfrey Mundy – he of the Antipodean dinner – accompanied the 10th Governor, Charles Fitzroy, on a tour inland. Fitzroy himself kept hunting dogs at Government House at Parramatta, used for hunting dingo in “imitation of the good old English sport of fox hunting”. But the real challenge it seems was kangaroo hunting.

In the late 1700s the Macarthurs’ kitchen at Elizabeth Farm was augmented with kangaroo meat and wild duck, hunted by an armed man on foot around Parramatta, to around 135 kilos a week. The assistance of expert indigenous hunters and trackers was a boon to the colonists – but in bitter irony this also quickly stripped the surrounding land of the game that the indigenous people themselves relied on. In 1805 the Sydney Gazette recorded the traditional burial near what is now Central of a man named Carraway[e], who was described as “a faithful guide to our bush sportsmen in search of the pheasant” (Sunday 22 December 1805). The word ‘sportsmen’ is interesting here, as it denotes a move from hunting primarily for food, to the gentlemanly pastime of hunting. In 1825 the visiting Hyacinthe de Bougainville took part in a hunt held in the Cowpastures, on horses borrowed from the Macarthurs’ stable at Camden Park. The rugged terrain was far from the more rolling landscape of an English estate:

…so much so that beyond a certain point it is impossible travel on horseback. Everywhere there are tracks left by wild cattle. We entered the forest with the hounds and the whips whose horses were accustomed to kangaroo hunting. Soon however we realised that it would be impossible for us to proceed without risking dangerous falls. Accordingly, we abandoned the pack and took our position on a vantage point to see it pass, but in vain. However much Mr Macarthur made the woods ring with the harmonious sounds of his hunting horns, we were unable to spot the pack even from the summits of the hills towards which we decided to head… [1]

Far from a single man on foot, the hunters were now setting out with trained hunting dogs and prize horses, housed in expensive stables.

Kangaroo dog owned by Mr Dunn of Castlereagh Street, Sydney by Thomas Balcombe, 1853. State Library of NSW ML 335

But back to Mundy, who wrote of a kangaroo hunt held for Fitzroy near Wellington in central New South Wales:

November 30th – This day was devoted by some of the resident gentlemen to an attempt to show the Governor the sport par excellence of the country – kangaroo hunting. In a long day’s ride ee only found one kangaroo, a red-flyer, a strong and fleet animal not less than 5 feet high. A shrill Tally-ho from one of the finest writers I ever saw made all the dogs spring into the air. Two of them got away on pretty good terms with our quarry, however the red-flyer showed us quite ‘another pair of shoes’, and a pretty fast pair too, and after our short burst of 12 or 14 minutes, both dogs and men were fairly distanced.

As humans and dogs have learned to their peril, kangaroos are in no way defenceless. The ‘boxing kangaroo’ isn’t a fairground cliche:

At bay the kangaroo is dangerous to young and unwary dogs from the strength with which he uses the long sharp claw of his hind foot, a weapon nearly as formidable as the wild boar’s tusk. The animal, when hard pressed, not [infrequently] takes to a water hole, where from his stature he has a great advantage over them, ducking them under water and sometimes drowning them as they swim to the attack.

First, catch your bandicoot

Writing in 1863 in his Bush Wanderings, Horace Wheelwright thought “The kangaroo, as a wild animal, stands about on par with the park deer at home”. He also described in grisly detail that is quite shocking to a modern reader how to hunt possum, platypus and koala. He also included bandicoot, which takes us back to where this circuitous chat began. Mrs Rawson, a Queensland author, advised this was “a very disagreeable animal to clean… the flesh can be left in strong vinegar and water a few hours before dressing. Sweet potatoes and onion make a good stuffing for bandicoot, which is good either boiled or baked”. Flying foxes she advised could be “stuffed with breadcrumbs and herbs or mashed potato. A young flying fox, split like a spatchcock and grilled, is a capital breakfast dish” [3]. I think I’ll stick to toast and Vegemite…

But what to do with your kangaroo? While Wheelwright praises a quick broil – “just cut off a steak from any fleshy part, and throw it on the ashes to grill” – he also gives this recipe for Kangaroo Ham which tasted to him “as much like reindeer hams as anything I ever tasted”:

Kangaroo Hams

15 lbs of saltpeter, 1/4 lb of carbonate of soda, mixed cold in a tub, the brine strong enough to float a potato. Don’t boil the brine. The above quantity is enough to make 50 hams. Cut the [kangaroo meat] nicely into shape; if the bone is taken out, the better for soaking, but the shape of the ham is not so well. Soak the hams in the brine for five days, occasionally turning them: when properly soaked, hang them to dry… If they are smoked, which adds to their flavour, a proper smoking house should be knocked up; a tent chimney will do… It is always as well; to have a tub of brine in every bush tent on the kangaroo-grounds, for the meat is much improved.” [2]

He also notes that “the tails make famous soup, when served up by Mr Williams in Melbourne as ‘kangaroo steamer'” But that’s a recipe for next week.

Sources

[1] The Governor’s noble guest: Hyacinthe de Bougainville’s account of Port Jackson, 1825 / translated and edited by Marc Serge Riviere. Carlton, Vic.: Melbourne University Press, 1999.

[2] Horace Wheelwright, Bush wanderings of a naturalist : or, notes on the field sports and fauna of Australia Felix / by an old bushman. London, 1865

[3] Mrs Lance Rawson. The Australian Enquiry Book of Household Information. Pater & Knapton, 1894.