Currently at various Sydney Living Museums Houses we’re running a series of night time tours, where you can see the houses as their original occupants saw them lit by candle and lamplight. Which raises the vexing question of just HOW should you light the historic dining table?

I say ‘vexing’ because when you read 19th century advice books the authors can get into quite a spin on the subject. The 19th century saw great advances in lighting technology, coupled with social change that saw dining hours move well into the evening for many houses. Candles gave way to lamps, and lamps to gas or electricity. And all the while the debate raged as to just which lighting was best to eat by.

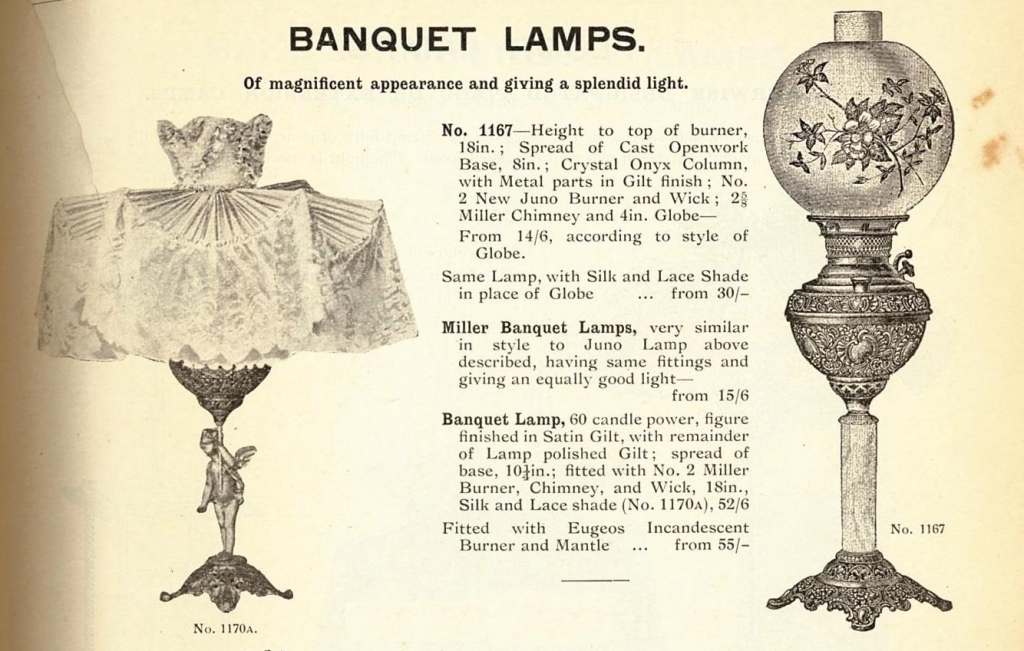

In considering historic interiors, such as dining rooms, you have to realise first of all that how we often see experience them today or see them in photographs, lit by electric light, is far from how they were understood by their original inhabitants. Especially when reliant solely on candles, lighting levels were far lower, and more like ‘puddles of light’ in many cases. Arrangements of furniture and ornaments were typically seen more as ‘vignettes’, which is why a full-blown Victorian interior can be so visually overpowering when lit with all-encompassing electric light. While some late 19th/early 20th century ‘banquet’ lamps were capable of throwing an amazing amount of light with multiple wicks and complex vents, many still only provided the equivalent of a handful of candles: a 60 watt globe today is the rough equivalent of 50 candlepower.

When first built in 1793, Elizabeth Farm was lit by candles – wax in the best rooms, through to cheap tallow in the service areas. As fortunes improved lamps were added. The Argand lamp, named for its inventor, employed a gravity fed reservoir that fed heavy whale or colza oil to a circular wick, which increased airflow to the flame. These could be suspended over the table, placed on mantles or on the table itself. Whale oil burnt cleanly, giving off little smoke and with an (apparently) agreeable aroma. Candles also improved; spermaceti candles blended with whale oil burnt far brighter, and incorporated new plaited wicks that burnt far cleaner and for longer. Like Argand lamps, these white candles were, however, found only on the affluent dining table. It was also said that soft candlelight was more flattering to a lady’s complexion, and its gentle flicker certainly set off silverware and gilt ornaments to greater advantage.

Enter stage left: the kerosene lamp

The brighter kerosene, also called paraffin lamp (kerosene extraction was patented in America in 1854) was on the whole significantly cheaper and available in a myriad of styles with many imported from the United States and common in Australia after the 1860s. These featured an inner glass chimney (from the familiar bulbous shape to quite narrow cylinders) and sometimes an outer decorative shade of glass or fabric. As refining technology advanced the characteristic ‘kerosene smell’ was also diminished. Rouse Hill House was probably lit by kerosene lamps for at least three quarters of a century until electricity was introduced in the early 1950s, and there are many lamps and lamp parts in the collection. You can see the transition to the clearly: wiring snakes across walls and ceilings to where new fittings have been installed. Above them, old smoke stains still mark the ceilings.

For many years the dining table was also lit by a pair of lamps with small, cylindrical wicks and decorative pink shades that provided a soft light at the diners’ eye level, while their stark white glazed lining reflected a brighter light onto the table surface. At Meroogal, Nowra, June Wallace remembered her aunts gathering around the dining table lit by lamps for supper, after which one end of the table was used for writing and the other for reading. A colleague of ours told us a story of her grandfather who read the newspaper after dinner by a single lamp at one end of the dining table, while his children played games at the other. A slow tug-of-war ensued, as the lamp was surreptitiously slid in one direction whenever he was distracted, then determinedly pulled back when the days news was plunged into gloom.

Serving table in the dining room at Rouse Hill House, lit by lamps. Photo Scott Hill © Sydney Living Museums

Gas

Viewed by many with great suspicion, gas lighting first appeared in Sydney in 1826: “GAS LIGHTS IN AUSTRALIA! An ingenious person of the name of Wilson lit up his house in Pitt-street on Monday last with Gas. He is entitled to a medal, and it is unfortunate for merit, that we have no society for the encouragement of the Arts and Sciences to award one” (The Monitor , Friday 16 June 1826) but was not becoming common in affluent urban houses until the mid century. Elizabeth Bay House was fitted with imposing ‘gasoliers’, as seen in this view of the library just before the cedar bookcases were removed:

The library, Elizabeth Bay House by Thomas Lawlor, c1935. Caroline Simpson Library & Research Collection, Sydney Living Museums

At Susannah Place ‘pay as you go’ gas meters were installed sometime after 1897. These fed a pendant lamp and a single gas cooking ring. Patricia Thomas, who lived at Susannah as a child recalled: “The gas was run by a meter and we had to put a penny in the slot and we always had to have those pennies to put in the slot otherwise we’d have to sit in darkness and many times we’d be in the middle of a meal and all of a sudden the light would go out!” [1] Gas lighting was resisted by many in dining rooms because of its often harsh, unflattering white light.

“The great object at its centre”

‘Tabitha Tickletooth’ – actually the English actor Charles Selby (c1802-1863) – made a similar comment about gas for lighting in London in 1860: “Gas is of course entirely out of the question, especially in London, now the Companies are consolidated and stringent agreements are necessary to be made, upon which the supply can at any moment be cut off.” [2] Selby’s satirical “The dinner question” discussed appropriate dining, menus, ‘service a la Russe’ – and lighting. His nom de plume “Tabitha Tickletooth” (he appears in drag on the frontispiece) posited: “On the best mode of lighting a dinner-table there are many opinions. Should the light be on the dinner table or over it [i.e. suspended from the ceiling] , or should rays be thrown upon it by strong reflectors from the walls?” [S]he quotes ‘Russian Dinners’, from Fraser’s Magazine for Town and Country which, with its theatrical allusion, I half-suspect he may actually have written:

The lighting of the dinner-table is always a matter of importance. Light and enjoyment ever go together. The gloom of hell, and the exceeding brightness in Paradise, surpassing all that is known on earth, are among the strongest points of contrast brought out by Dante in his descriptions of the place of woe and the place of happiness. …[t]his is the kind of punishment sometimes inflicted upon a miserable set of unoffending fellow creatures by a parsimonious or ill-judging entertainer. Not often, certainly ; and the abundant variety of good lamps, with the existing cheapness of oil and candles, now leave no excuse for any deficiency of illumination.

The light should be as much as possible concentrated on the table, and in a small party it will be desirable to shade the eyes of the guests by semi-transparent reflectors of some kind, which will throw nearly all the light on the table. This, of course, only applies to lamps; the more diffused light of several candles requires no such caution….

The proper study of the dining-room is dining, and whatever tends to divert the eyes from the table is wrong in principle. As in a theatre, where the looks of the spectators should be riveted by every artifice upon the scene of performance, so in a dining-room should all the accessories of necessary furniture be subordinated to the great object which occupies its centre. Here there can hardly be too much light. The table, and the faces of the guests round it, alone demand attention, and for them the greatest amount of illumination should be reserved. [3]

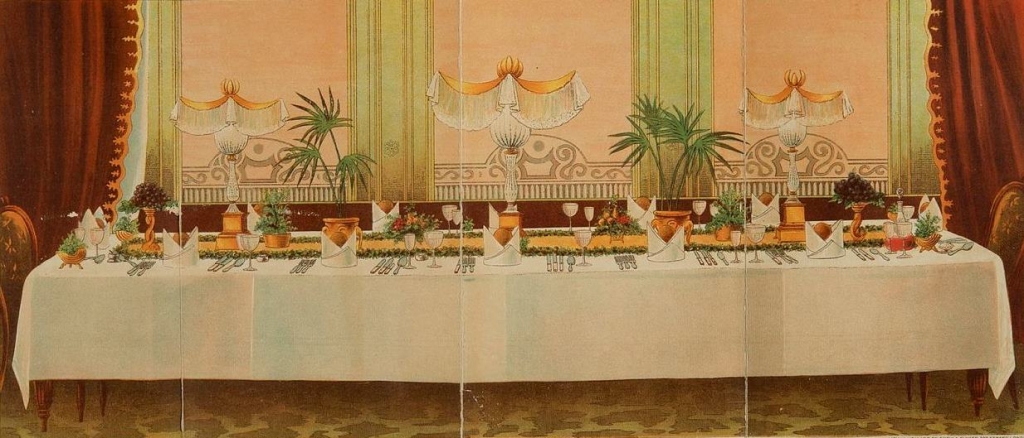

In this plate from Mrs Beeton’s Everyday Cookery (c1895) the a la Russe setting is dominated by an extravagant set of three banquet lamps (set on a fringed runner, outlined in greenery and interspersed with vases, tazzas of grapes and potted palms), with a wire-framed fabric shade supported on thin outer arms, which diffused the light at eye level while reflecting more light onto the table surface:

‘Dinner table laid for 12 Persons’ in Mrs Isabella Beeton, Beeton’s Everyday Cookery and Housekeeping Book, Ward, Lock & Co., London, [ca.1895]. Caroline Simpson Library & Research Collection, Sydney Living Museums RB640 BEE/1

‘Banquet lamps’ in Anthony Hordern and Sons’ household catalogue, Anthony Hordern & Sons, Sydney, 1907. The Caroline Simpson Library & Research Collection, Sydney Living Museums TC 658.871 HOR/2

Dining room lighting is still a matter of debate and indeed satire. I know Ive been to restaurants where torches were provided to diners so they could read the menu in the dim light – and Ive been known to (not always discreetly) use the torch on my phone.

Why not come along to see these houses lit as their occupants knew them? Meroogal is running a night time tour on August 2nd, and at Rouse Hill we’re opening the doors on the 22nd and 23rd of August. You can also see Vaucluse House, Elizabeth Bay and the Hyde Park Barracks! Click here for more details.

Notes

[1] Excerpt from Patricia Thomas’s oral history of life at Susannah Place. See curator Anna Cossu’s ‘A Place in the Rocks‘, Sydney, Historic Houses Trust of NSW, 2008 p101

[2] Tabitha Tickletooth (Charles Selby), “The Dinner Question, or how to dine well and economically”, London 1860, facsimile reprint Prospect Books, 1999.

[3] “Fraser’s Magazine for Town and Country“, Volume 59. London, John Parker & Son, 1859.