By the end of the 19th century an entirely new form of dining had taken over the fashionable table. Forget the Francaise, join us as we dine a la Russe!

Throughout the 19th century dining styles changed fundamentally, with implications for the appearance of the table, how food was served and eaten, and the order in which it arrived. The point of change can be dated to around 1810 to 1814, when the style favored by the Russian court was first served in Paris, possibly (depending on which account you read) by the Russian Ambassador Prince Borisovitch Kourakine.

If you go by The Servants’ guide and family manual (London, 1831) service a la Russe (or dining ‘in the Russian style’) hit the fashionable tables of London with a bang in early 1829. The description is loose, and indicates a style in transition:

In the arrangement of large dinners there has lately been much novelty introduced: the dinners given at the houses of some noblemen during the season of 1829 having been served in the style termed a la Russe, which consists of the dessert being placed on the table at the same time with the first course, forming together four lines of dishes; after the second course is removed, the dessert, which had been previously arranged next the plateau or candelabras in the centre, is now drawn forward, and then occupies the place of the second course. By this method much bustle is avoided during the repast, especially where a large company is assembled, and it has been found decidedly a very superior plan; the appearance of the table is also extremely elegant. On these occasions, the large joints are usually carved at the side-table, and the entrees, as well as the second-course dishes, are handed round.

(The London ‘season’ then ran from around February when Parliament sat till July or August). Its a bit confusing, but what is being described is a setting where elements of the dessert are ON the table from the start, in rows down the centre. The defining point is that the larger dishes are carved at the sideboard and brought individually to the diners who serve themselves. This description of actual Russian tables is far clearer:

[The dishes] are presented to the guests by the maitre d’hotel and his assistants, already carved at the side-tables, and one after the other, with the pleasing attention of whispering into your ears the name of each dish. One comes and another goes, and a servant follows, with a decanter in each hand. The first commends to your attention a little vareniky; the second, finding that you have already before you a dish of stachy brings round the rastingay, or oblong pastry to eat with it. He of the bottles thinks it high time to remind you of such cordial beverages as champagne, burgundy, lafitte, paxarete, vin du commandeur, du johannisberg, de la comete, and so on until you know not which wine to take.

I’m sure they managed. This 1894 definition is clearer:

The habit we have of eating everything very hot and very fast comes to us from the “Russian service”: it differs from the French service in the very fact that nothing hot appears on the table, everything is cut up as needed, either in the kitchen or pantry [or at the sideboard]. The carving should be performed very neatly, having all the pieces of even size and placed at once symmetrically either in a circle or straight row on dishes for ten or less persons, then passed round to the guests, who help themselves or are helped, according to their wish. (Charles Ranhofe, The Epicurean. The author, New York, 1894).

Back to Francaise

Part of the recreation of a symmetrical a la Francaise setting, filmed for the Eat Your History exhibition. Photo Scott Hill © Sydney Living Museums

If we jump back to the Francaise style, you can clearly see the difference, and understand the implications that the Russe style had for table service, serving arrangements and decoration. In this style of dining, all the dishes of the first course were pre-laid on the table, in a symmetrical arrangement, before the diners entered. At one end typically a roast, at the other soup. These serving dishes were replaced by those of the second course. Ultimately, the table could even be stripped back to polished wood (causing the ‘bustle’ mentioned above that disrupted large dinners) and the dessert course served. Here is a Francaise setting also recreated in the dining room at Rouse Hill:

An a la Francaise table setting created at Rouse Hill House. Photo © James Horan for Sydney Living Museums

Dinner is served

Its with the adoption of the Russe style that we also see the familiar sequence of dishes we recognise today established, starting with the entree, and moving from savory through to a sweet dishes: entree, soup, fish, meats, vegetables, dessert, cheese course.

Apart from the requirement for extra staff to carry dishes around, the upshot of serving from the servery or sideboard meant that a considerable amount of table space was now empty. And, like nature, an aspiring hostess to out make an impression abhors a vaccuum. Lamps, nicknacks, flower vases, potted palms, fringed runners, mirrors, were all pressed into service. Along with a series of glasses, ranks of cutlery also appear, becoming increasingly specialised for individual foodstuffs or dishes (think of the scene where the ‘salad fork’ is explained in the film ‘Gosford Park’). Enteremets – savory or sweet dishes to be admired and picked at between courses – and dessert items such as hothouse fruits likewise.

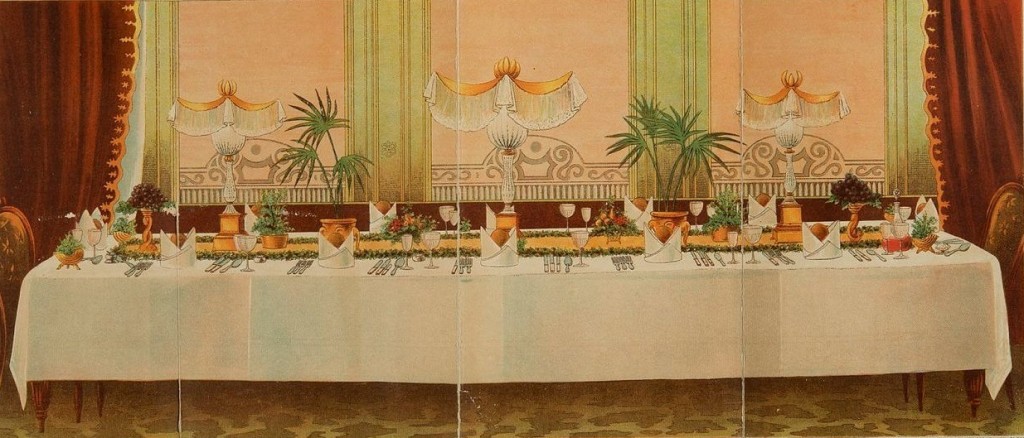

Here are views of an 1890s Russe setting from Beeton’s every-day cookery and a recreation of such a setting at Rouse Hill, using pink glass table lamps given to Bessie Rouse by Miriam Thorburn for her dining table:

Dinner table laid for 12 persons in Mrs Isabella Beeton, Beeton’s every-day cookery and housekeeping book, Ward, Lock & Co., London, [ca.1895]. Caroline Simpson Library and Research Collection, Sydney Living Museums RB640 BEE/1

Tinkering round the edges

The Russe style was slow to be universally adopted, and many guides published right up to the early 1900s still used and endorsed the Francaise style. This rant is part of a lengthy piece entitled ‘The Great Dinner Question”, from the Hobart Courier of 1859:

Tastes are not to be changed in a day, and when people dine in a certain way, we may feel pretty sure that although they don t know any better, it is very much also because that way is entirely consistent with their taste. You may take the sturdy fellow who stands out for the single joint, or who vociferates, ‘give me a good rump steak, Sir, and you may have all the kickshaws for me,’-and show him a dinner a la Russe-as the best way of dining; he will laugh at you. Prove to him that to dine off several well-cooked dishes is more whole-some and nutritious than swallowing an immense piece of semi-raw beef ;-what cares he? It is his taste and was his father’s before him, and may be his son’s, unless the Times or some other public instructor inculcates more civilized principles. If these things are to be mended, it must be by slow degrees, and as the taste of the nation is gradually becoming better in matters of art and dress, so we may one day hope to have the ‘ feeding habits’ of the middle classes rather more assimilated to the principles of good taste than at present, even though they may not quite come up to the high standard of Gr. H. M., the Lucullus of Berkley Street. (The Courier, Hobart, 14th April 1859).

It also had its critics (Antoine Careme being the most notable), and those who suggested a hybrid version far closer to the version described in the 1831 Servants’ Guide that emphasised the best of both styles: the showiness of Francaise, with the practicality of Russe. In this excerpt the compromise is termed ‘Anglo-Russe’:

MASSEY AND SON’S

ANGLO-RUSSE, NEW SYSTEM.

When the a la Russe system was first introduced into England, it was with the view of promoting the comfort and convenience of the guests—first, by serving the viands from the sideboard while yet hot and in perfection; and, secondly, by saving them the trouble of carving. It answered the purposes required, and very soon the a la Russe, or Russian manner of serving the dinner, became the universal fashion.

Many, however, regretted that the artistic work of the cook (especially in the second course) should not be seen, as it is invariably cut into or otherwise disfigured long before it has passed round the table.

It is now three years since we first proposed to remedy this by advancing a system which (as the entremets for dress dinners are generally cold) should combine the advantages of the a la Russe with the elegant effect of “dinner on the table.” This is by serving the first course in the a la Russe style and the second course “on the table,” spaces being left between the dessert dishes for the entremets, &c…. We have tried it with the greatest success.

And of course J. and W.J. Massey were the perfect caterers to call on to make this all happen.

Hungry for more?

The table settings at Rouse Hill were created using the collection at that property. As the original knives do not survive in the collection, early 20th century examples have been used instead.

The best depiction in film I can think of that illustrates the Russe style are the magnificent dinners in Martin Scorcese’s The Age of Innocence (1993).

John & William John Massey, Massey and son’s biscuit, ice, & compote book; or, The essence of modern confectionery. London; Simpkin, Marshall & Co., 1866.