Now that we’ve gone through Elizabeth Bay’s cellars, it’s up the servants’ stairs and on to the table. Claret anyone?

Wines from Elizabeth Bay’s cellars were originally carried up a staircase that twisted, serpent-like, all the way from the cellar, past the four mezzanine rooms with their tiny windows, through the attics and up to the roof. Later blocked to separate the underground rooms from the main floors, this was the steep ‘back stair’ used by the Macleay’s and Onslow’s servants.

The original servants’ stairs as they emerged into the cellars at Elizabeth Bay House. Photo Scott Hill © SLM

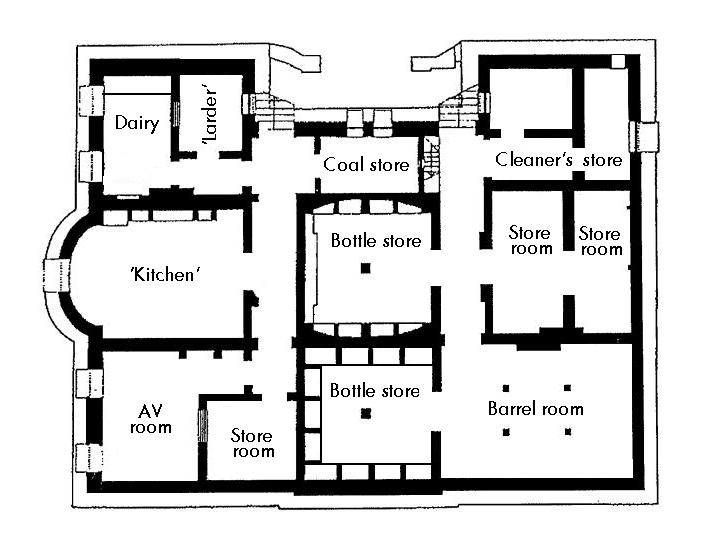

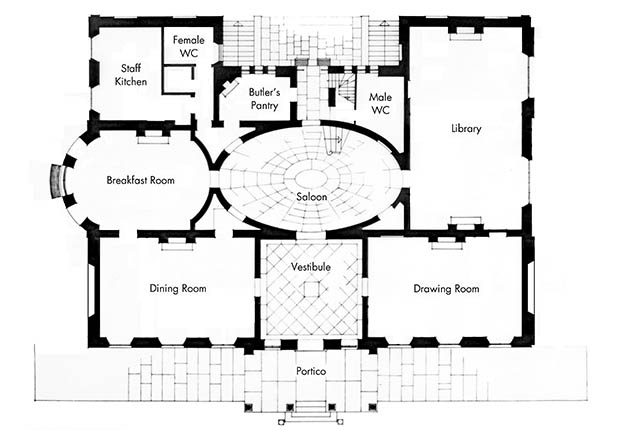

Still ‘behind the green baize door’, crossing the small back lobby led to the butler’s pantry, which faces onto the rear service court. Here the contents of bottles were transferred into decanters or claret jugs – like these superb 1839 examples (top image) presented to Thomas Barker, a friend of Macleay’s. The wine had most likely already been clarified in the cellars, though it would receive a last filter through muslin-lined funnels. Only then was it carried across the saloon to the dining room. You can read more about these spaces, and the planing of Elizabeth Bay House, in the online guidebook.

Drinking customs at the Victorian table were carefully, and increasingly, proscribed as the century progressed. The under-the-table rum-fuelled drinking bouts of the Regency that were satirised by Hogarth were actually going out of fashion by the late 1820s, with punch in particular forming less of a feature of a gathering. In Sydney, Governor after Governor acted to quell ‘public drunkenness’, usually with little effect. As Jacqui noted it was hoped that a shift from spirits to wine would also modify drinking behavior. What goes around…

The wine list

In 1831 the [deep breath] Servants’ guide and family manual, with new and improved receipts arranged and adapted to the duties of all classes of servants (John Limbird, London) advised on what was being served, albeit on a wealthy London table. It demonstrates the shift to a wider range of wines – wines that Macleay would know well from his days in the wine trade. Some were available in the colony, as demonstrated by the labelled bottle bays in the cellar, but as wines did not always survive long sea voyages it was a great incentive to the burgeoning local industry.

The custom during the last century [the 18th] was always to take, after soup, a glass of some sweet wine; but now the experienced wine-drinker takes either a glass of good old Madeira, or of Teneriffe. Common wines are only served with the roast meat, such as sherry &c. and if French, the vin de Beaume [described as “the best kind of claret” and served by “men of large fortunes”] is drunk at the second course. The third course is exhilarated [what a word!] by Hermitage, Cote-roti and champagne. After dinner, old Port, Muscadel, or malmsey Madeira, Cyprus wine. And Tokay; this last high priced and powerful wine is served in very small glasses.

An “esteemed civility” at the table

Prince Pückler-Muskau, who we met in his discussions of English habits, described the English customs of drinking at table at the time of Alexander Macleay and Governors Brisbane, Darling and Bourke. Rather than ‘free drinking’, he notes that it was obligatory in polite circles to ‘toast’. This meant securing the complicity of another thirsty diner. It was a custom his Germanic sensibility had little time for:

“It is not usual to take wine without drinking to another person. When you raise your glass, you look fixedly at the one with whom you are drinking, bow your head and drink with great gravity. Certainly many of the customs of the South Sea Islanders, which strike us the most, are less ludicrous. It is esteemed a civility to challenge anybody in this way to drink; and a messenger is often sent from one end of the table to the other to announce to B— that A—- wishes to take wine with him; whereupon each, sometimes with considerable trouble, catches the others eye, and goes through the ceremony of the prescribed nod with great formality, looking at the moment like a Chinese mandarin. If the company is small, and a man has drunk with everybody, but happens to wish for more wine, he must wait for the desert, if he does not find in himself the courage to brave the custom…

(I suspect that quite a few found they were sufficiently courageous!) He continues with the dessert:

“Three decanters are usually placed before the master of the house, generally containing claret, port, sherry or madeira. The host pushes these on stands, or in a little silver wagon on wheels, to his neighbour on the left. Every man pours out his own wine, and if a lady sits next to him, also helps her; and so on until the circuit is made, when the same process begins again. Glass jugs filled with water happily enable the foreigner to temper the brandy which forms so large a component of English wines. After the dessert is et the servants leave the room; if more is wanted the bell is rung and the butler (Haushofmeister) alone brings it in. The ladies sit a quarter of an hour longer, during which time sweet wines are sometimes served, and then rise from the table.” [1]

And at that point ‘free drinking’ could begin. Cheers!

References

[1] Fürst Hermann Von Pückler-Muskau (1785 – 1871), Tour in England, Ireland, and France: in the years 1826, 1827, 1828, and 1829. With remarks on the manners and customs of the inhabitants, and anecdotes of distinguished public characters. in a series of letters by a German prince, Carey, Lea & Blanchard, Philadelphia, 1833