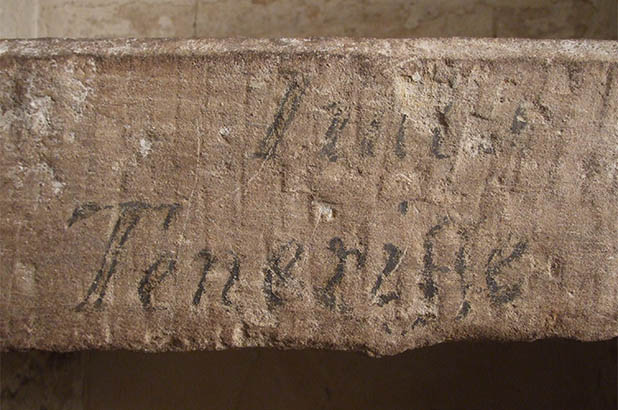

One of Elizabeth Bay House’s most evocative spaces is its wine cellar, built under the mud-stone floor of the entry hall and saloon. Faint impressions of painted labels – sauternes, Teneriffe, port, claret, sherry, brandy, are still evident on the arched storage bays designed to hold casks and bottles. The wine cellars were connected to the house with an internal staircase, giving the butler – who was entrusted with the keys – access to the wine store.

Wine and ‘sobriety’

Wines were imported from Europe, the Canary Islands, and from the Dutch colony at the Cape of Good Hope – sweet Constantia being its specialty. Wine grapes were planted in Sydney by Governor Phillip in 1788, and other settlers experimented with wine growing in, most notably Philip Schaeffer, Gregory Blaxland and the Macarthurs, who were the first to find real success in wine making. Local wine quality was questionable, and alcohol content tended to be very high, sometimes because brandy was added to help their keeping quality. But as the 19th century progressed, wine drinking was encouraged as the government advocated ‘sobriety’ – which did not necessarily mean abstinence, but a more responsible drinking culture – a call we hear still today. Wine was seen as a preferential alcohol to the customary spirits and strong ales still favoured by most of the population.

A health tonic

Wine was being promoted for its health benefits and many ‘wine doctors’ had interests in wine production – starting with Dr Redfern who established a wine-producing vineyard in NSW in 1818, purporting wine as a malnutrition and scurvy deterrent. Prescribing a pint of wine per day for transported convicts would surely have helped develop his business model (?!!). Drs Lindeman (Carwarra, Hunter Valley c1850s), and Angove (Maclaren Vale South Australia, 1886) whose brand names are still marketed today, followed this trend. Physician and health reformer Philip Muskett had much to say about the merits of Australian wines and the need for styles lighter in character and in alcohol content, in his prescient treatise The Art of Living in Australia, first published in 1893. It took almost 100 years for Australians to heed his advice.

Colonial tastes

Tastes in wine seem to have been much sweeter in the 19th century, and higher in alcohol than we expect today. Fortified wines such as sherry, port, sauternes and toquay style wines were very much in favour. If you are wanting to host a colonial style or period dinner, Shiraz, Cabernet Sauvignon (claret) or other blended style reds would be suitable. Reisling, Verdhello and sweeter Muscat or German style whites (commonly referred to as ‘hock’, short for Hockheimer), style wines would be appropriate whites for the table. Sherry would be served before dinner or at the table with the soup, proceeding onto other table wines with more substantial dishes. Champagne might be served with desserts (what we’d now regard as the cheese course), and for toasts, and port and brandy to linger at the table with.

The Macleays and wine

The Macleays were early colonial wine growers, establishing vineyards at their property Brownlow Hill in Camden in the 1830s, not far from the Macarthur family’s Camden Park estate. The Macleay family had quite a history with wine – Alexander Macleay’s first job, aged 19, was with a wine merchant in London, William Sharp in 1786. Sharp must have made a strong impression on him, as the Macleays named their eldest son William Sharp Macleay (b.1792). The cellars, integral to the design of Elizabeth Bay House, stand testament to Alexander’s interest in wine, even if only for his own consumption! William Sharp Macleay lived at Elizabeth Bay house from 1845, no doubt enjoying the benefits of his own wine stores, until he died in 1865. The house was then passed on to another William – Sir William John Macleay, renowned natural scientist (founder of the Macleay museum at the University of Sydney), politician and winemaker.

Wolonjerie wines

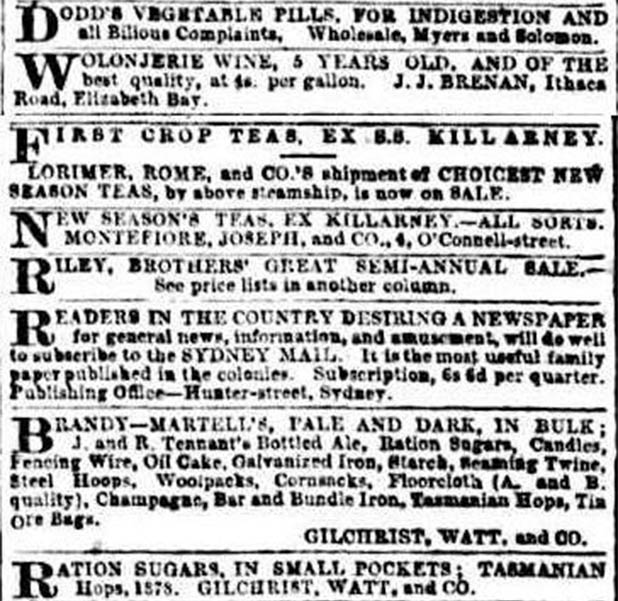

Sir William produced wine from his property on Lake Albert in Wagga Wagga, in south-western NSW, under the ‘Wolonjerie’ label. His 33 acres under vine at Wolonjerie resulted in (using the contemporaneous spelling) Scyraz (shiraz), Verdilho, Riesling and blended wines (Malbec, Goreais, Aucarot). The wines were made and blended at the vineyard, then transported to Sydney in oak barrels by ox-cart. It’s not surprising that as the district’s member on the Legislative Council, William was instrumental in extending the NSW railway system to Wagga!

Advertisement for Wolonjerie wine, The Sydney Morning Herald, 30 July 1878, p 4. Retrieved 15 July 2013 from http://trove.nla.gov.au/ndp/del/article/13413790

The oak barrels stored in the cask room under Elizabeth Bay House, and William employed cellar-men to bottle the wine and distributed his wines from there. Wolonjerie wines were advertised in Sydney and district newspapers, and found a ready market in ships passing through Sydney, convincing their captains of the merits of his wines. The bottling and distribution operation out-grew the undercroft cellars at Elizabeth Bay House and he commissioned a purpose built iron cellar on the estate, on Ithaca Road, at the cost of £200 which unfortunately, has not survived. William used his social standing to get personal endorsement from the Governor of NSW, entered his wines in the Great Exhibition in 1879. Not only did he display his wines, William sold them to the Exhibition caterers – astute businessman! He served his Wolonjerie wines to the many eminent guests at dinners held here, and at his home in Elizabeth Bay, making tasting notes in his diaries.

The cellars beneath the house remain on view and are occasionally used as a venue for wine tastings and functions, and even weddings!